The Last 100 Days: Obama’s Biggest Mistake edition

Ever since the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, presidents have been judged on the successes they notch during their first 100 days. Now, as Barack Obama prepares to end his historic turn on the political stage, Yahoo News is running The Last 100 Days, a look at what Obama achieved during his consequential presidency, how he navigates the struggles of his last months in office and what lies ahead for him after eight years filled with firsts. We will also look at how the country bids farewell to its first African-American president.

It’s not a literal 100 days — Obama leaves office in late January 2017.

And it won’t all be about policy. As Obama himself is fond of noting, he also spent his two terms as father to daughters Malia and Sasha and husband to first lady Michelle Obama. And even without much input from the White House, the cultural landscape shifted dramatically over his two terms on issues such as gay rights.

And then there’s the way the president sees the presidency — not just his tumultuous years at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., but also the institution and its relationships (for better or worse) with other branches of government and with the news media.

In this 12th installment, we look at Obama’s answer to the classic question modern presidents frequently face: What was your biggest mistake?

_____

Being president of the United States provides immense power and almost limitless opportunities to screw up.

And commanders in chief do screw up in ways large and small, and the results can be devastating or merely annoying, historic or just the focus of an awkward news cycle.

Asking presidents to reflect on their biggest mistake can shed light on how they view the power, and the limits, of their office, or how they might approach a future problem that resembles the one they think they handled inadequately.

The question can also provide someone at the apex of American politics with the opportunity to deliver an insincere, self-serving answer, like the job seeker who makes a show of confessing in an interview that their biggest shortcoming is that, gosh, they are a perfectionist. It’s also important not to confuse “biggest mistake” with “biggest regret” — a mistake is something that should have been done differently, a regret might be something beyond even a president’s control.

George W. Bush infamously bungled John Dickerson’s question on the matter. Among the Bush press corps, it became known as “the Dickerson Question.”

At an April 13, 2004 press conference in the East Room of the White House, Dickerson, the Time magazine reporter who now hosts “Face The Nation” on CBS, stood up and asked then President George W. Bush this:

“In the last campaign, you were asked a question about the biggest mistake you’d made in your life, and you used to like to joke that it was trading Sammy Sosa. You’ve looked back before 9/11 for what mistakes might have been made. After 9/11, what would your biggest mistake be, would you say, and what lessons have you learned from it?”

A Bush communications aide, asked to remember the experience, told Yahoo News “it didn’t feel like a tough question in the asking, even though there were obviously lots of bad ways to answer it,” especially with Bush’s reelection fight that year. “We just didn’t think he’d have, you know, this level of bad,” the aide said ruefully of Bush’s response.

Bush’s answer could be boiled down to this: I know I’ve made some mistakes, but can’t think of any, and certainly not the Iraq War. But he drew it out in a painful way.

“I wish you would have given me this written question ahead of time, so I could plan for it,” he said, to laughter from the press corps. He went on, “John, I’m sure historians will look back and say, Gosh, he could have done it better this way, or that way. You know, I just — I’m sure something will pop into my head here in the midst of this press conference, with all the pressure of trying to come up with an answer, but it hasn’t yet.”

Bush defended his handling of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and even seemed to hold out hope that he’d be vindicated on the question of whether Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction.

And then Bush wrapped up his answer. “I hope I — I don’t want to sound like I’ve made no mistakes. I’m confident I have. I just haven’t — you just put me under the spot here, and maybe I’m not as quick on my feet as I should be in coming up with one,” he said.

“God, it fed into all of [the media’s] portrayals of him as stubborn, out of touch, unable to admit mistakes,” the communications aide recalled.

Even though Obama will soon leave the office, studying his self-diagnosed “biggest mistake” and what lessons, if any, he has learned carries greater weight now, with U.S. forces entangled in the president’s undeclared but escalating war against the so-called Islamic State, also known as ISIS.

When it comes to his biggest mistake, Obama’s critics on the left and right will have their own suggestions. But the president himself has weighed in on a couple of occasions since he took office, most recently in an April 2016 Fox News interview.

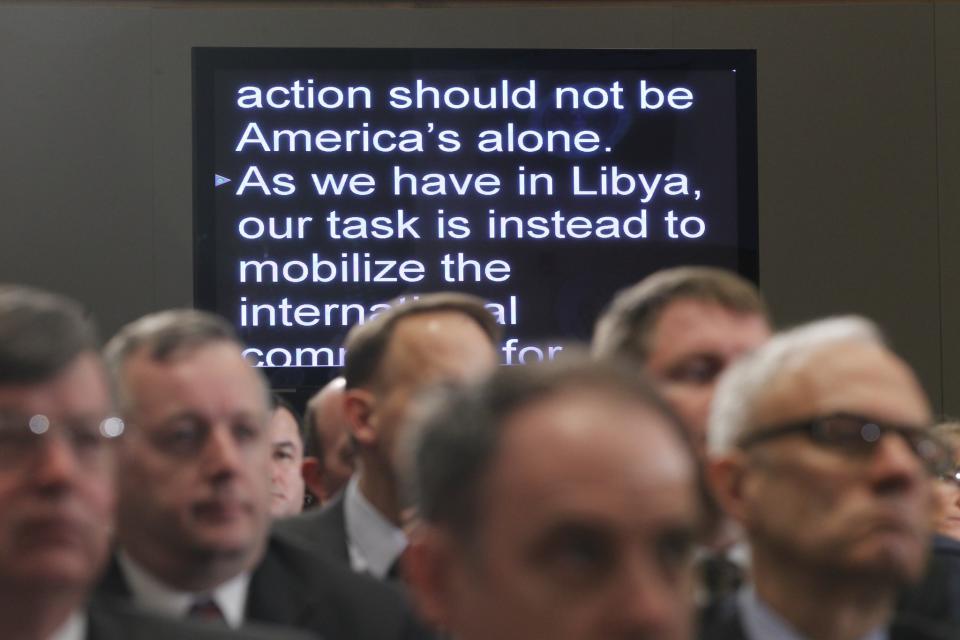

“Biggest mistake?” host Chris Wallace asked. “Probably failing to plan for the day after what I think was the right thing to do in intervening in Libya,” Obama replied in an all-too-brief exchange.

Obama’s answer to the Dickerson Question has evolved over time, and while it doesn’t have the same cringe-factor as Bush’s response, it’s worth some scrutiny.

In July 2012, with his reelection campaign in full swing, Obama was asked in a CBS interview to assess his first-term failures.

“The mistake of my first term, couple of years, was thinking that this job was just about getting the policy right,” Obama said. He continued, “And that’s important. But the nature of this office is also to tell a story to the American people that gives them a sense of unity and purpose and optimism, especially during tough times.”

Obama reflected that the doubts about him during the 2008 campaign — when “everybody said, ‘Well he can give a good speech but can he actually, you know, manage the job?’” — had by 2012 morphed into: “‘Well, he’s been juggling and managing a lot of stuff, but, you know, where’s the story that tells us where he’s going?’” And, the president admitted, “I think that was a legitimate criticism.”

Obama concluded, “Getting out of this town, spending more time with the American people, listening to them, and also then being in a conversation with them about where do we go together as a country, I need to do a better job of that in my second term.”

It’s hard to imagine an easier crowd pleaser than Obama’s Washington-is-bad-the-American-people-are-good offering. But it’s not that his answer was insincere, necessarily. Obama aides today broadly defend the idea that he got the policy substance right and the sales pitch wrong. (Obama did, however, promote his White House communications director at the start of his second term.) But they acknowledge a certain political convenience, in that the answer amounted to what one top adviser recently described to Yahoo News as a “most uninteresting” response — one unlikely to dominate a news cycle with talk of presidential weakness or failure.

By December 2013, the disastrous Obamacare rollout trumped the communications lapses. Obama called the busted HealthCare.gov website his biggest mistake and took responsibility.

“Since I’m in charge, obviously we screwed it up,” he said. “And it’s not that I don’t engage in a lot of self-reflection here. I promise you, I probably beat myself up even worse than you [ABC’s Jonathan Karl] or [Fox News correspondent] Ed Henry does on any given day.”

Over the past two years, Obama’s answer has shifted again, from Obamacare’s rollout to the failure to rebuild Libyan institutions after helping the rebels who toppled and killed dictator Moammar Gadhafi. Upon learning of Gadhafi’s killing in October 2011, Hillary Clinton responded: “We came. We saw. He died.”

In an August 2014 interview with the New York Times, Obama defended the decision to be part of “the coalition that overthrew Gadhafi” as “the right thing to do,” and argued, “Had we not intervened, it’s likely that Libya would be Syria.”

At the same time, he told the Times, “I think we [and] our European partners underestimated the need to come in full force” to rebuild post-Gadhafi Libyan society. “That’s a lesson that I now apply every time I ask the question, ‘Should we intervene, militarily? Do we have an answer [for] the day after?’” Obama said.

Without using the “biggest mistake” language, Obama again delivered a public mea culpa of sorts about Libya in his September 2015 speech to the U.N. General Assembly.

As he did on Fox News and in the Times, Obama cast the military intervention as the right thing to do “to prevent a slaughter” since Gadhafi was vowing to massacre residents of the city of Benghazi.

Obama admitted at the U.N. that “even as we helped the Libyan people bring an end to the reign of a tyrant, our coalition could have and should have done more to fill a vacuum left behind.” And, he said, America and its partners “have to recognize that we must work more effectively in the future, as an international community, to build capacity for states that are in distress, before they collapse.”

This would seem to be an especially wrenching admission for a president who regularly excoriated Bush for the wretched handling of post-Saddam Iraq.

But in an April 2016 piece in the Atlantic, based on multiple interviews, Obama basically shifted the blame for his “biggest mistake” onto allies Britain and France.

“When I go back and I ask myself what went wrong,” Obama said, “there’s room for criticism, because I had more faith in the Europeans, given Libya’s proximity, being invested in the follow-up,” he said. He pointed out that Nicolas Sarkozy, the French president, lost his job the following year. And he said that British Prime Minister David Cameron quickly became “distracted by a range of other things.”

Everyone has a friend who’s been in a relationship like this, in which one person ducks blame by saying, “My real mistake was thinking too highly of you.” But aides deny that Obama was trying to absolve himself for what he privately calls a “s*** show,” according to the Atlantic.

Whether or not Obama was shifting the burden elsewhere, he has had to draw his own lessons from Libya. That country has been locked into what one top White House aide called a “one step forward, one or two steps back” dynamic that includes the presence of ISIS terrorists (and American airstrikes on those forces).

Libya is hardly the only problematic country from Obama’s tenure in office, and White House aides cite a number of other examples on the “lessons learned” front.

The president’s critics often say one of his greatest mistakes was his 2013 decision not to enforce his “red line” against Syria’s use of chemical weapons. But according to Obama’s aides, military strikes on forces loyal to strongman Bashar Assad could have led to worse chaos in Syria, beyond even the bloodshed that has left as many as 470,000 people dead, by some estimates. Toppling Assad without a plan for filling the vacuum he would have left, they say, would have risked putting all of Syria ultimately under ISIS control, dramatically expanding the threat to key U.S. allies like Turkey or Jordan as well as Iraq, and threatening to pull America into a much wider conflict.

Administration officials also point to Obama’s ongoing resistance to providing Ukraine with lethal defensive weapons to fend off pro-Moscow forces in the country’s east. In their telling, the risk of escalation if Ukrainian forces killed Russian troops with American weapons is unacceptable.

Finally, they cite the current U.S. deployment in Iraq and, to a lesser extent, Syria. In their version of events, Obama held off on all but the most urgent military action — sending a small force to protect the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, launching airstrikes in Syria and intervening to save civilians of the Yazidi religious minority who were besieged on Mount Sinjar by ISIS forces — until Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was pushed from office in 2014. Once Haider al-Abadi, seen in Washington as a much more reliable partner, took over, Obama dramatically ramped up U.S. operations. In this argument, Obama again connected a de facto political vacuum to prospects for American-led military success and future stability.

Whether these were the right or wrong lessons to draw from Libya — or the right decisions at all — is a matter of heated debate that won’t be settled here.

Obama himself may at least partly settle the argument before he leaves office, or in a few years, if the experience of his two immediate predecessors is any guide.

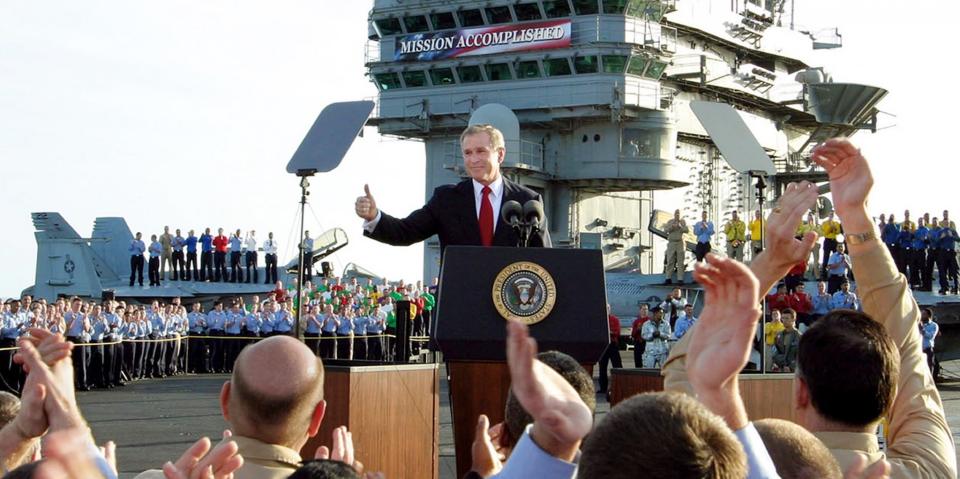

At his final press conference, on Jan. 12, 2009, Bush faced a variant of the Dickerson Question, and this time it seemed to catch him in a more thoughtful mood.

“I have often said that history will look back and determine that which could have been done better, or, you know, mistakes I made,” Bush began.

But he noted that his May 2003 appearance on an aircraft carrier in front of a giant “Mission Accomplished” banner “sent the wrong message.” He allowed that “some of my rhetoric has been a mistake” — a reference to cowboy talk like wanting Osama bin Laden “dead or alive.” His only reference to Hurricane Katrina was to criticism of his Air Force One flyover on his way back to Washington from vacation in Texas — a decision he defended — not to the botched government response to the devastating storm. He said it was a mistake to push the partial privatization of Social Security after his 2004 reelection — a failed legislative drive that badly damaged his political standing.

Bush also pointed to the detainee abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib prison and the absence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. “I don’t know if you want to call those mistakes or not, but they were — things didn’t go according to plan, let’s put it that way,” he said.

“There is no such thing as short-term history,” he concluded. “I don’t think you can possibly get the full breadth of an administration until time has passed: Did a president’s decisions have the impact that he thought they would, or he thought they would, over time? Or how did this president compare to future presidents, given a set of circumstances that may be similar or not similar? I mean, it’s just impossible to do. And I’m comfortable with that.”

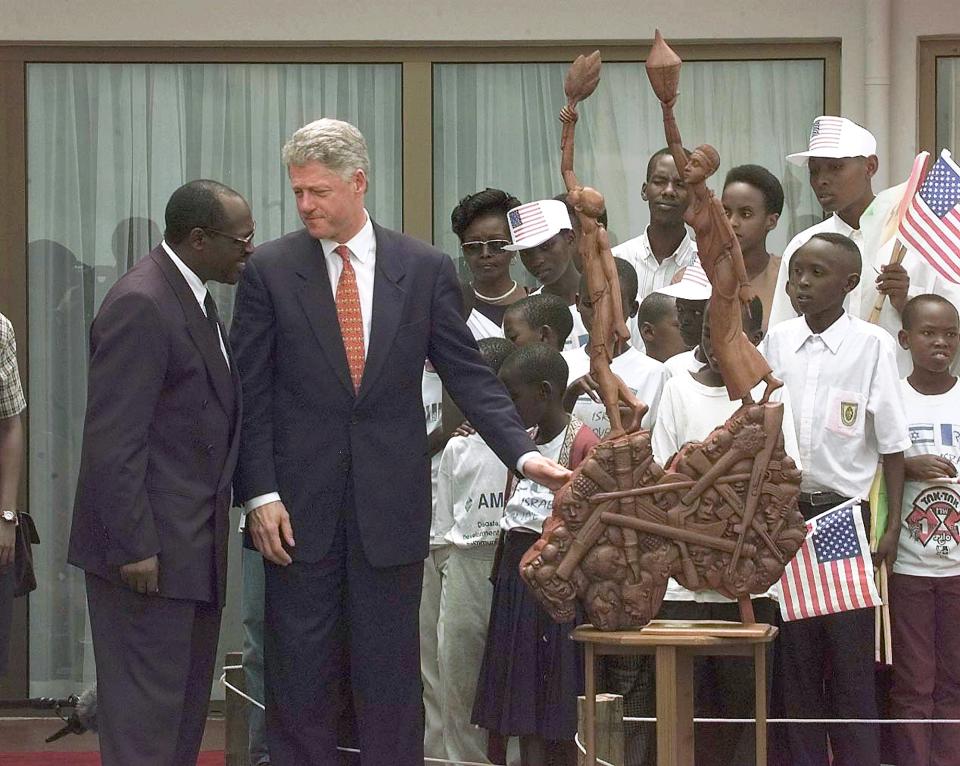

Bill Clinton provided a different model for presidential soul-baring in a June 2004 CNN interview.

What was your biggest mistake in the office, asked host Larry King.

“We know what my biggest personal mistake was,” Clinton replied, in an obvious reference to his affair with former White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

But as president, he suggested, one of his biggest mistakes was spending his first two years trying to pass a sweeping health care reform bill, having underestimated the resolve of Republicans to block it.

And “one of my great regrets in foreign policy is not sending troops to try to stop the Rwandan genocide when I realized how severe it was,” Clinton said of the 1994 mass murder of minority Tutsis by majority Hutus. “It happened very fast, 90 days, 10 percent of the country, 700,000 people killed with machetes. I feel terrible that we didn’t do it.”

Clinton explained that, at the time, his administration was “still reeling” from the 1992-1993 Somalia intervention, immortalized in the movie “Black Hawk Down.” He was also trying to mobilize support to help Haiti and intervene in Bosnia.

Acting in Rwanda, Clinton said, “was never seriously considered.”

“And when I finally came to grips with the magnitude of it,” the former president said, “I will always regret it.”