The long shadow of racism in medicine leaves Black Americans wary of a COVID-19 vaccine

As the coronavirus pandemic has progressed, and the need for a vaccine has become more urgent and apparent, the number of Americans who say they would take such a vaccine keeps falling. In particular, Black Americans — who have been among those hit hardest by the pandemic — are resistant to the idea. A new Yahoo News/YouGov poll found that only 27 percent of Black Americans and 46 percent of white Americans plan to get a coronavirus vaccine if and when one becomes available.

The perceived politicization of the vaccine process and unprecedented pace of Operation Warp Speed has led to doubts nationwide. Until very recently, President Trump was predicting that a vaccine could arrive ahead of Election Day, Nov. 3, contradicting members of his own coronavirus task force, who have repeatedly given less optimistic time frames that have turned out to be more realistic.

But whether a vaccine is ready next month or next year, many Americans may not trust it, even after it is approved by the Food and Drug Administration. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey published in September found that 62 percent of Americans worry that political pressure from the Trump administration will lead the FDA to rush to approve a coronavirus vaccine without making sure it’s safe and effective. Whether that will change if a new administration is in office after Jan. 20 remains to be seen.

Dr. Peter Marks, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA and self-proclaimed “FDA point person on COVID-19 vaccines,” wrote an op-ed Tuesday in USA Today attempting to alleviate those concerns.

“We hope to ensure public confidence in COVID-19 vaccines by being transparent about FDA’s decision-making process,” he wrote. “Whether a vaccine is made available through an EUA [emergency use authorization] or through a traditional approval, FDA will ensure that it is safe and effective.

“Trust means everything.”

Trust, experts say, is crucial to Americans’ willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. But for many Black Americans, that trust will be difficult to earn after a long history of exploitation and abuse by the health care system has led them to be wary of the U.S. medical establishment.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study is the most famous example. Sponsored by the U.S. Public Health Service, the project enrolled uneducated Black men in the South without informing them of the purpose of the experiment, which was to study the natural progression of the disease. Participants went untreated for years after an effective cure had been discovered. A 1972 Associated Press story on the experiments, observing that “human beings with syphilis” had been “induced to serve as guinea pigs,” caused public outcry and finally brought the study to an end after 40 years. By then, some participants had already infected others, and some had died of the disease’s late effects.

But there are other reasons why Black Americans are suspicious of medical experiments that seek to enlist their cooperation.

“It’s the example that the government has admitted to and acknowledged,” Harriet A. Washington, author of “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present,” told Time of the Tuskegee study in 2017. “It’s so famous that people think it was the worst, but it was relatively mild compared to other stuff.”

The 1619 Project documents medical abuse perpetrated on Black Americans since the country’s inception, when painful experiments were performed on enslaved people by physicians like Dr. Thomas Hamilton, who in the 1820s was “obsessed with proving that physiological differences between black and white people existed.”

Washington spoke with the family of Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old Black woman who had samples of cancerous cells taken without her knowledge or consent during treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Lacks died in 1951, but a line of those cells, known as “HeLa,” was used in groundbreaking medical research while doctors and scientists failed to ask her family for consent as Lacks’s name, medical records and even her cells’ genome were released to the media and eventually published online. Nature reports that HeLa cells are still used today, including in research for vaccines against COVID-19, while some researchers who use HeLa cells have concluded that they should offer overdue financial compensation in the form of grants to Lacks’s descendants.

Such invasive and often horrific stories go back generations, but racial discrimination in health care is anything but ancient history. A recent poll by the Undefeated and the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 7 in 10 African Americans believe people are treated unfairly based on race or ethnicity when they seek medical care. And persisting disparities in care for Black and white Americans were highlighted during racial justice protests this year, with the American Psychological Association stating that “we are living in a racism pandemic.”

Today, African Americans are more likely to die at earlier ages from all causes, and more likely to have preexisting conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure. African Americans have 2.3 times the infant mortality rate of non-Hispanic whites, and the pregnancy-related mortality rate for Black women is four to five times higher than for white women, according to 2007-2016 national data, regardless of socioeconomic background.

A 2016 study also found racial biases among white medical students and residents, who were more likely to prescribe pain medications to white patients than Black patients because of false beliefs that Black patients have higher pain tolerance than white patients.

Consequently, distrust of the medical establishment among many in the Black community runs deep.

“This distrust is not unique to COVID,” explains Dr. Uché Blackstock, a Yahoo News Medical Contributor and CEO of Advancing Health Equity. “It’s preexisting, just like the health inequities are preexisting. And I think that what the pandemic did is sort of expose the distrust even further and more significantly because there’s more urgency to this issue.”

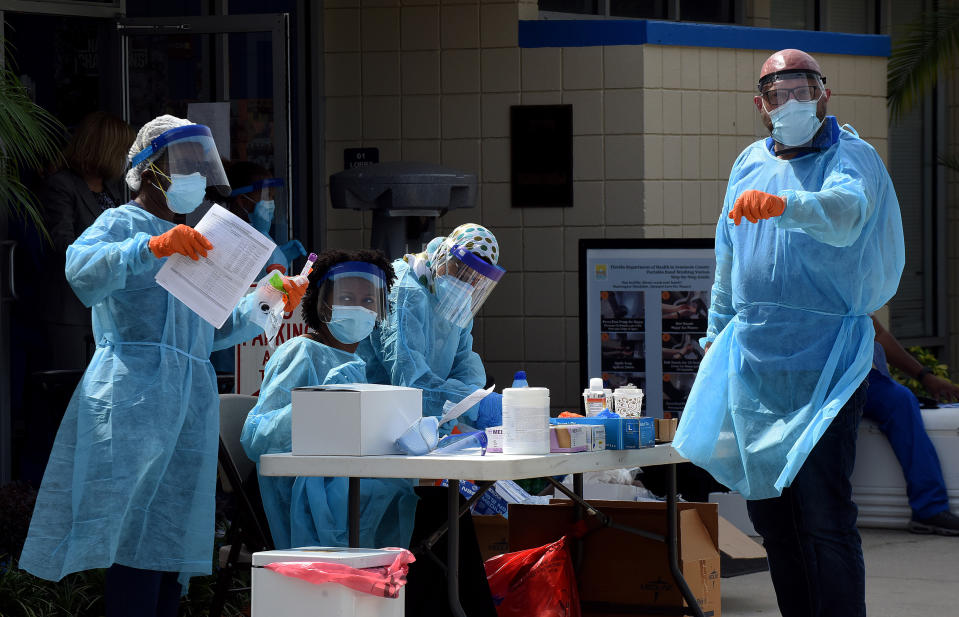

The African American community has been hit particularly hard by the coronavirus pandemic, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledging that long-standing discrimination in health care and housing plays a major role. COVID-19 death rates among Black Americans are 2.1 times higher than among white Americans and hospitalization rates are 4.7 times higher, according to the CDC. Reluctance to take a vaccine could compound an already deadly problem.

Blackstock says that’s a major reason why the extremely low level of Black participation in clinical trials for coronavirus vaccines needs to be corrected.

“We need an adequate representation of Black Americans in these vaccine trials because it’s Black communities that are being most disproportionately impacted by the virus,” Blackstock said. “And so while there is no biological difference between people of different races, what we know is that racism actually shapes the health of these communities. And so we need to see how people from varying communities respond to the vaccine.”

Blackstock says that for many Black Americans, transparency will be key to increasing the number of people willing to take a vaccine — and to participate in vaccine trials.

“The truth is, we actually know from the data that Black Americans are more willing to take part in clinical trials when they’re told about the risks and the benefits fully of the trial, as well as the benefits not only to the individual, but to the community,” she explains.

In an effort to build more trust among Black Americans, the National Medical Association — the largest organization of Black physicians — has formed its own task force to vet FDA recommendations around coronavirus therapeutics and vaccines.

“It’s necessary to provide a trusted messenger of vetted information to the African American community,” Dr. Leon McDougle, a family physician and president of the NMA, told Stat. “There is a concern that some of the recent decisions by the Food and Drug Administration have been unduly influenced by politicians,” he said in reference to the agency’s authorization of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 patients, which was later revoked.

And for messaging on a coronavirus vaccine to be truly effective, Blackstock says, messaging and outreach need to be done in conjunction with trusted leaders and members from within the community. It’s also a model that Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, says has been crucial since the HIV/AIDS epidemic, when engagement from within Black communities helped protect those who were most vulnerable.

“You want to go into the African American community with people who look and think and act like the people you’re trying to convince,” Fauci said during an interview with BET in July. “You get the community people on the ground to go in and say, ‘Hey, let me tell you, I’ve scoped this out. This is something for your own benefit.’”

But Blackstock emphasizes that public health outreach to Black communities shouldn’t be limited to COVID-19.

“In the long run, these efforts should be ongoing,” she said. “This is not just a one-time thing with this pandemic, and forming long-term relationships with communities will be incredibly crucial.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: