'The Wild West': Questions surround Trump legal team payments

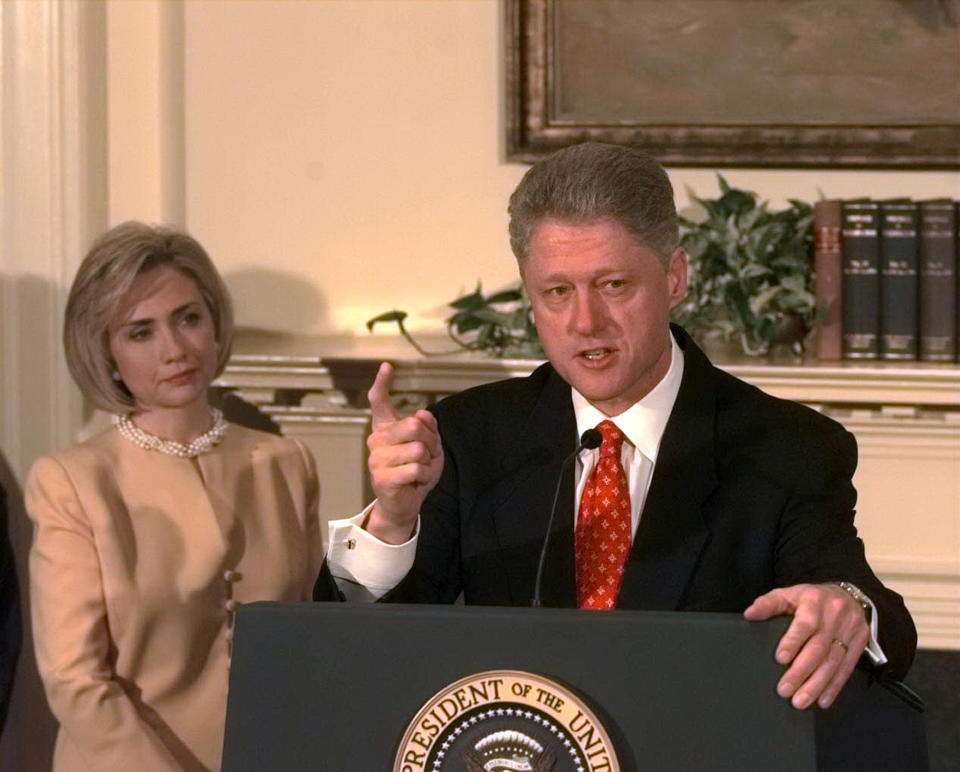

In 1994, as a slew of scandals were popping up around President Bill Clinton, an attorney who worked with his defense team visited the Office of Government Ethics (OGE) in Washington to ask a simple question in person: Could the president of the United States accept free legal services from his personal lawyers?

An unambiguous answer came back from the OGE, the executive branch’s in-house experts at preventing conflicts of interest: No.

“An inquiry was made very early on after the president retained legal counsel,” the attorney, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Yahoo News. “Meetings were held with the OGE, and the OGE advised that any provision of legal services would have to be done at market rate.”

The OGE’s concern, the attorney explained, “was the appearance of undue influence.” In other words, a lawyer providing the president with free legal services, or a donor who subsidized those services so the president would not have to pay out of his own pocket, might appear to have substantial leverage over America’s most powerful elected official.

Flash forward 25 years, and President Trump is doing things very differently. Former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, the most high-profile member of the personal legal team during both the Russia investigation and the Democrats’ ongoing impeachment inquiry, is providing free legal services to the president.

In an interview earlier this month with Yahoo News, Giuliani responded with an unequivocal “Yes, sir” when asked if he is representing Trump pro bono, including covering expenses. Jay Sekulow, Trump’s other main personal attorney, says his work for Trump is paid, but declined to say by whom or how much.

Until now, Trump’s legal arrangements have been in a gray area of regulation, but critics are trying to change that and the OGE is currently considering establishing new rules for how members of the executive branch can pay for their personal legal needs.

Craig Holman, a lobbyist for Public Citizen, a nonprofit, nonpartisan foundation dedicated to combating corruption, has petitioned the OGE to establish guidelines covering personal attorneys for executive branch officials. Holman, who testified before the office earlier this month, described the current situation — where there are few guidelines and it is unclear where Trump’s lawyers are getting their money from — as “the Wild West.”

“The Office of Government Ethics has never until now started developing any consistent rules and regulations to govern legal expense funds for the executive branch,” Holman said. “So if you go back and take a look at the few opinions they’ve offered over the course of the last several decades, you’ll find them completely contradictory and inconsistent.”

The term for free legal services, “pro bono,” is a shortening of the latin phrase pro bono publico, for the public good, and therefore not taking a fee.

Giuliani declined to answer follow-up questions about his legal work for Trump, but Sekulow, who is paid, said he didn’t see anything wrong with that arrangement. “Pro bono is exactly that. It’s pro bono,” he said.

Sekulow declined to discuss any specifics regarding his payment as part of Trump’s legal team, including the amount or source of payments. “I don’t discuss my fees situation,” he said. “... I don’t discuss ever what the fee arrangements are, but I’ve been compensated.”

While Sekulow wouldn’t discuss details, he insisted that there wasn’t anything improper being done. “I can’t discuss how we’re being paid, but it’s obviously appropriate,” Sekulow said.

However, other leading lawyers and legal experts who spoke to Yahoo News believe there are problems posed by Trump receiving free legal services from Giuliani.

Charles Fried, a Harvard Law professor who served as solicitor general under President Ronald Reagan and serves on the board of the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center, said it would be “obviously problematic” for Trump to have a member of his legal team working pro bono.

“He is ... receiving hundreds of hours of legal services, which, you know, people like Giuliani charge a thousand dollars an hour. [Trump is] getting that for free,” Fried said.

Until the OGE issues new rulings, the issue of presidential legal representation will likely remain sparsely regulated, in part because there is limited precedent for a president needing extensive personal legal services. In the 1990s, when Clinton’s lawyers went to the OGE, the president’s use of a team of personal attorneys for a major case was largely uncharted legal territory in the landscape of new regulations enacted after the Watergate scandal.

In Clinton’s case, ultimately, the OGE advised his attorneys on how to set up an independent trust that would raise money to pay his lawyers — referred to interchangeably by ethics experts as a “legal defense fund” or a “legal expense fund.”

In late 2018, the office began a rule-making process to provide a broader framework for executive branch officials’ legal expenses. Holman expects that the OGE’s rule-making process will go beyond creating rules for legal expense funds to cover parallel subjects like the free legal services Giuliani provides to Trump. “It will address all the issues related to legal services for public officeholders, including pro bono and crowdsourcing,” he told Yahoo News.

Scott Amey, general counsel of the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan watchdog group, also said the OGE had been too slow to act. Amey said new guidelines could come from the rule-making process, but in the meantime, officials should proceed cautiously.

“Legal defense funds and pro bono legal services offered to any government employee, including the president, raise a host of conflict of interest and ethics questions that require answers,” Amey said. “The Office of Government Ethics is seeking advice and might have a rule or guidance in 2020, but government ethics officials are facing this problem now, and any decisions about receiving money or services should be handled with the public interest in mind.”

The OGE declined to comment. Two other personal attorneys who worked for Trump during the special counsel investigation, John Dowd and Emmett Flood, also declined to comment. William Consovoy, who represented Trump before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and recently argued that the president would have immunity from criminal investigation or prosecution even if he shot someone on Fifth Avenue in New York, did not respond to a request for comment.

Even if the OGE comes up with a set of new rules covering the president, it’s unclear what impact that would have on Trump. Typically, the OGE makes recommendations to the executive branch or, in criminal cases, referrals to the Department of Justice, but rules from the office are nonbinding, and it is up to the other federal agencies whether to follow the OGE’s guidance.

The Trump administration has previously run afoul of federal ethics watchdogs and ignored their recommendations. In February 2017, the office recommended that the White House consider taking disciplinary action against Kellyanne Conway, a counselor to the president, after she gave an apparent endorsement of the private business of Ivanka Trump, the daughter of and an adviser to the president, in potential violation of the Hatch Act. A White House lawyer responded by brushing off the issue.

The administration appears to be taking the same attitude toward any questions over legal services.

Sekulow, Trump’s attorney, said he and his team have not consulted with the OGE. “I’m not a government employee. I don’t get near that,” Sekulow said of the ethics office.

White House counsel Pat Cipollone did not respond to requests for comment.

Even though Trump would not necessarily have to abide by any future OGE rules on legal counsel, there are laws that govern his conduct. The president is exempt from much of the regulation that bars other executive branch officials from taking gifts worth over $20; however, the president is subject to bribery laws and is prohibited from taking gifts “in return for being influenced in the performance of an official act.”

Tony Essaye, a retired attorney who was the executive director of one of Clinton’s legal defense funds, said pro bono work would raise “a lot of issues and questions ... as to where people are giving free services to the president they get a certain degree of influence.”

Essaye offered a broad example: “If you’re doing a lot of work for me free, if you come to me and say, ‘Look, I’ve got a friend who I would like you to do this for, or that for,’ I’m more inclined to be willing to do that because I appreciate what you’ve done for me.”

Based on past cases, Paul Light, a New York University professor of public service and former director of governance studies at the Brookings Institution, predicted regulators would eventually determine that Trump should be charged market rate for legal services.

“The history of this is that a fair market value is determined not by the president, not by the White House, not by presidential counsel of any kind, it’s to be determined by the federal government,” Light said. “This isn’t Donald Trump’s call. This will be eventually the call of a federal bureaucrat.”

Light said Trump’s legal team should be keeping meticulous records and tracking their billable hours. “To be on the safe side, one would urge any president, not just Trump ... to register the pro bono gift of legal services for future review,” he said.

Sekulow would not comment on how his team is tracking and charging for their work. “I’m not going to discuss our billing, but we send bills and get paid,” he said. “That’s all I’ll say.”

The opacity surrounding Trump’s legal defense, which doesn’t include a fund, is very different from how it was handled with Clinton.

Back in 1994, to address the OGE’s concerns about the appearance of undue influence, the Clintons’ legal team determined their legal defense fund would have a number of voluntary safeguards. It would have a $1,000 individual contribution limit and semiannual reports disclosing its donors, and it would be forbidden from advertising or soliciting donations and from accepting money from political action committees, corporations, lobbying groups, professional associations or labor unions.

Ultimately, there were two trust funds established for the Clintons’ legal defense — and they provided a dramatic example of how the president’s legal expenses could be an attractive target for outside interests seeking to gain influence with the White House.

Bill and Hillary Clinton established the first fund in 1994 as the president faced legal issues, including a sexual harassment suit from Paula Jones. The fund ran into trouble when Ya Lin “Charlie” Trie, a restaurateur from Clinton’s home state, delivered a manila envelope full of hundreds of thousands of dollars in money orders. Some of the money was linked back to a Taiwan-based organization that had chapters in the United States.

After a series of meetings at the White House, the donations were returned. Trie was later indicted in connection with other suspicious donations to the Democratic National Committee and pleaded guilty to campaign finance violations.

By 1998, as the Monica Lewinsky scandal loomed, donations were no longer coming into Clinton’s original legal defense fund as a result, in part, of what a CNN report termed “the embarrassment” that lingered after the Trie episode. Clinton’s supporters established a second fund that relaxed some of the strictures, increased the contribution limit tenfold, and permitted advertising and solicitations for donations.

Essaye, who was appointed to run that second fund, said the OGE also stipulated that the Clintons’ defense trust should not have the Clintons serve as its grantors, as they had with the first fund, since they were also the trust’s beneficiaries. This time around, the fund had independent leadership, and specific rules were put in place to make it independent of the Clintons’ control.

“The money would not go to the Clintons. It would go directly to the law firms, and that’s essentially what occurred,” Essaye explained.

By contrast, Trump’s arrangement with Giuliani and Sekulow, which doesn’t involve a legal defense fund, lacks these conflict of interest safeguards and offers no transparency.

“Trump just ignores all that stuff, I suppose,” Essaye said.

Neil Eggleston, who served as President Barack Obama’s White House counsel from 2014 to 2017, said Republicans “would have gone crazy and insisted on investigations and subpoenas” if Obama employed a personal legal team with undisclosed income sources, foreign ties and pro bono work.

However, he suggested the Trump administration is “just a different presidency” in how it addresses ethical and legal concerns, pointing out how White House officials pushed aside the OGE’s concerns about Kellyanne Conway.

“These kind of issues, they just don’t really pay much attention to,” Eggleston said of the Trump White House. “It’d be weird if they were cutting square corners on this when they don’t cut square corners on anything else.”

But the questions surrounding potential conflicts of interest could prove troublesome for Trump’s legal team, particularly for Giuliani, whose sources of outside income have attracted the attention of law enforcement agencies.

Giuliani has been linked to work in more than a dozen foreign countries through his former law firm, other legal work and his security consultancy. Two of his business associates, Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, were arrested on Oct. 9 and charged with illegally trying to direct foreign funds to American political campaigns. Federal prosecutors are reportedly investigating Giuliani’s relationship with the two men.

A lawyer for Parnas reportedly argued in Manhattan federal court on Oct. 23 that some of the evidence supporting the campaign finance charges against Parnas may be protected by executive privilege due to Giuliani’s simultaneous representation of Parnas and Trump. That unusual argument ties the criminal case directly to the White House.

Fried, Reagan’s former solicitor general, described the mix of Giuliani’s foreign ties and pro bono work for Trump as troubling. “He’s not allowed to take money from a foreign government,” Fried said of Trump. “He is, however, receiving hundreds of hours of legal services … for free, and Giuliani is able to do that, in part, because he’s making money representing foreigners. Why don’t you work it out?”

While Giuliani has attracted the most attention because of his pivotal role in the impeachment inquiry, the president’s other top lawyer, Sekulow, also has income sources that have come under scrutiny.

In addition to his work for Trump, Sekulow has a private law firm, and he and his family also operate — and receive substantial income from — a network of nonprofit charitable organizations that describe themselves as dedicated to religious advocacy. In the past two years, as Sekulow served as Trump’s attorney, he has shifted parts of his empire of nonprofits to focus on pro-Trump legal work.

Yahoo News reviewed four years of tax filings that showed that his main nonprofit fundraising entity, legally named Christian Advocates Serving Evangelism, took in over $216 million in aggregate revenue from 2015 to 2018. This money is largely from contributions, and while some of it flows through visible tributaries like professional fundraising vendors, other funds come from unknown sources into the charity’s coffers with no transparency of any kind. Nonprofits are not required to disclose individual donors, and it is unclear who is funding Sekulow’s various organizations.

The best-known charity associated with Sekulow is ACLJ, the American Center for Law and Justice, described as a law firm dedicated to protecting “religious and constitutional freedom.” ACLJ was founded in the 1990s by televangelist Pat Robertson and began its existence championing Christian conservative causes such as school prayer and opposition to abortion. During the Obama administration, the group began to pursue cases aligned with the Republican agenda, such as mounting legal challenges to the Affordable Care Act.

ACLJ sends funds to partner organizations around the world, but Sekulow at first said it doesn’t “get foreign money,” then offered a clarification.

“Now, I say we don’t accept foreign money. I couldn’t tell you every donor,” Sekulow said. “You know, we have hundreds of thousands of donors. But I don’t recall a situation where we’ve ever had what I would call a foreign donor. We don’t take government donations.”

Recently, Sekulow’s charitable organizations have taken on an increasingly pro-Trump bent. An analysis of ACLJ-National’s filings in federal district and circuit courts shows that, since the president was elected in 2016, 16 of the 31 cases the group has become involved in, either as a party or through friend of the court briefs, appear to be directly tied to either defending Trump’s policies, pursuing investigations that would be useful to his legal defense or simply to antagonizing his political opponents.

ACLJ’s most recent federal case is a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit that seeks records of former FBI Director James Comey’s communications with a person who was purportedly Comey’s confidential informant in the White House. ACLJ has also filed FOIA requests aimed at exposing Obama officials’ purported “unmasking” of the identities of Trump allies in connection with the Russia investigation and records related to Uranium One, a company that directed money to the Clinton Foundation amid a Russian takeover. The organization’s digital and radio platforms also regularly tout the work of Trump’s legal team and attack the impeachment inquiry.

On his daily radio broadcasts, Sekulow is fond of saying that he switches between “wearing my ACLJ hat or my lawyer for the president hat.” But even he said the ACLJ’s work has overlapped with some cases involving Trump because of the organization’s focus on “constitutional issues.”

Those charitable groups, which pay substantial sums to Sekulow and firms he owns, and whose donors are not identified, have also engaged in what appears to be pro-Trump advocacy.

Lloyd Mayer, a professor of law at Notre Dame, said this mixing of nonprofit and business also could be problematic from the standpoint of tax law. “If he is using the charity to benefit his private legal practice,” he said, “that would raise issues of private benefit,” among other concerns.

In other words, a tax-exempt charity like the ACLJ might not be permitted to support legal work that benefits a client — like Trump — whom Sekulow represents in his private practice.

However, Sekulow said the ACLJ is “very specific about ... making sure that the work of the ACLJ fits within the parameters” of its mission.

“Everything is done according to the rules and regulations with the Internal Revenue Service, and we’re meticulous in our accounting,” he said of the ACLJ.

Phillip Hackney, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh’s law school who focuses on tax law for charities, argued that IRS enforcement would ultimately be unlikely. Like many of the other aspects of Trump’s legal team, he said, the involvement of ACLJ in funding Sekulow and engaging in legal advocacy for the president falls into a “gray space” between providing a benefit to a private party and “litigating out important ideas” that “otherwise normally wouldn’t have an opportunity to present themselves.”

“It’s really hard for the IRS to do anything about it,” Hackney said. “It’s kind of hard for the IRS to make those distinctions in any way in which it does not come out itself seeming biased.”

With the IRS unlikely to act, it may ultimately be up to the OGE to determine what rules, if any, apply to Trump and his unusual arrangement for legal services. And nothing is likely to happen on that front before the impeachment inquiry and possible trial take place this year.

While the OGE is “taking it seriously now, they are not going to come up with anything until 2020 and probably after the election,” says Holman of Public Citizen.

“We are going to go into the 2020 election cycle with no rules governing how legal expense funds are handled or whether a lawyer can offer gifts of legal services or not,” he continued. “Literally, no rules, and worse yet, no transparency.”

_____

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: