The 'woke' primary: Democrats vie to do the most to fight racism

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

Systemic racism is America’s original sin. The Civil War abolished slavery. The civil rights movement helped African-Americans achieve basic equality in the eyes of the law. But even today, stubborn, structural injustices persist, reinforcing deep racial divides across every aspect of American life: housing, policing, business, education, health, wealth and more.

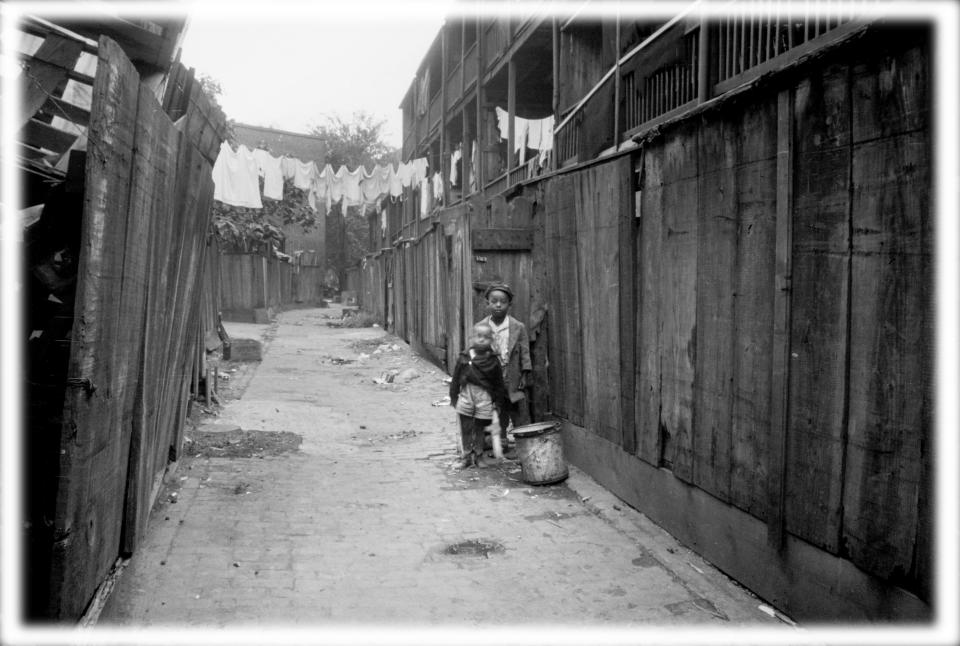

Consider some statistics. For every $100 in wealth (assets, not income) a white family has, the average black family has only $5.04 — and despite more than 150 years of political progress, that disparity hasn’t shrunk all that much since Abraham Lincoln was president. In 1863, black Americans owned one-half of 1 percent of the national wealth; today, it’s just over 1.5 percent. Even education doesn’t close the gap: the median wealth for black households with a college degree is still 30 percent lower than the median wealth for white households without a college degree.

And money isn’t the half of it. In America, black mothers are three to four times more likely than white mothers to die during or after childbirth. Black infants are more than twice as likely to die as white infants. Denied equal opportunities in the classroom by a dearth of adequate resources and discriminatory disciplinary policies, black students score, on average, two to three years behind white students of the same age on standardized tests. Black people are much more likely to be arrested for drugs, even though they’re not more likely to use or sell them. Black inmates make up a disproportionate share of the prison population — a disparity only partially explained by higher crime rates.

Meanwhile, nearly a century of local and federal housing discrimination has divided communities along racial lines, with three out of four neighborhoods that were redlined in the 1930s remaining low-income to this day. Many of these areas are literally toxic: Black Americans are 54 percent more likely than the average American to live in places with poor air quality, and black children are nearly twice as likely as children of other races or ethnicities to test positive for lead poisoning.

These problems aren’t new. But the collective response from the Democratic Party’s presidential candidates is. For reasons of both politics and principle, they have put forward by far the most ambitious “black agenda” — the most sweeping set of proposals to combat systemic racism — of any presidential primary field in U.S. history. If enacted, their policies would represent the biggest federal intervention on behalf of racial justice since the 1960s.

So what are they proposing? And why now?

During the 2008 presidential primary, Barack Obama’s advisers urged him not to talk explicitly about race; they worried the young senator with the Kenyan father and Muslim-sounding name might alienate moderate white voters. It wasn’t until Obama’s association with controversial pastor Jeremiah Wright threatened to sink his campaign in March of that year that he finally, begrudgingly, tackled the issue head on.

Obama’s team wasn’t wrong to resist. They’d simply learned the lessons of the recent past. In 1972, Rep. Shirley Chisholm of Brooklyn became the first African-American to campaign for a major party’s presidential nomination. When the Black Panthers endorsed Chisholm as “the best social critic of America’s injustices to run for presidential office,” she refused calls to reject their support. The party establishment — black and white — never took her candidacy seriously.

In the 1980s, civil rights activist Jesse Jackson twice competed for the Democratic nomination on a platform that emphasized racial justice. Seeking to assemble a “rainbow coalition,” Jackson criticized mandatory minimum sentencing and advocated for stricter enforcement of the Voting Rights Act, among other things. He did better than Chisholm, but still lost by wide margins both times.

History shows that in the general election, making a show of independence from the party’s African-American base, as when Bill Clinton strategically repudiated hip-hop MC Sister Souljah in 1992, can be a winning strategy for Democrats. Contrariwise, Michael Dukakis lost, in part, because George H.W. Bush tied him to a threatening black convict, Willie Horton.

As a result, Democratic presidential wannabes have long charted a middle course on race: more progressive than Republicans, but not to the point of actually confronting the daunting challenges of systemic racism. In short, Democrats have treated African-American voters — more than 90 percent of whom have voted Democratic in recent presidential elections — as a loyal constituency whose support they can largely take for granted.

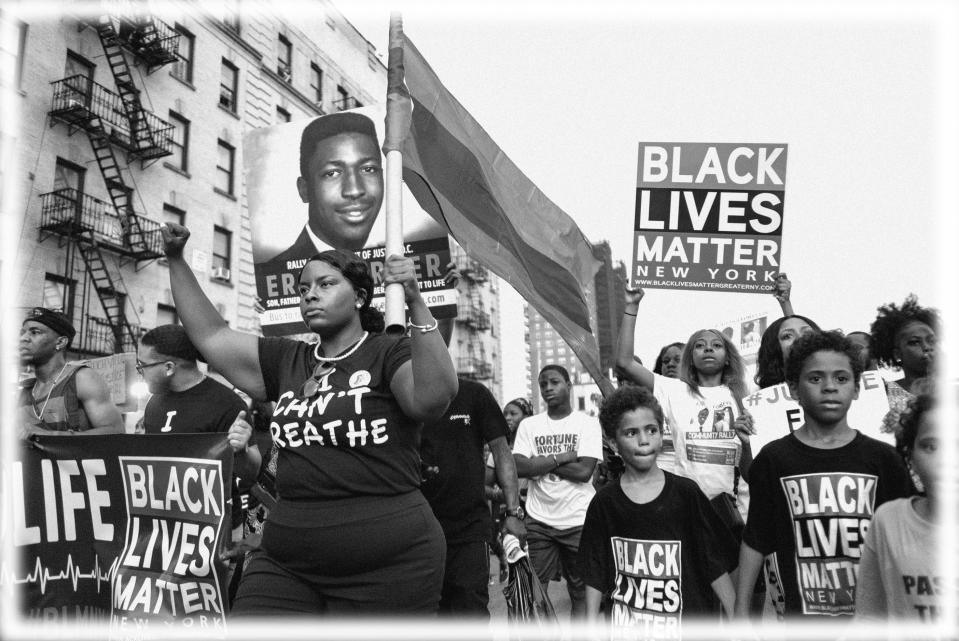

A lot has changed in the past few years, however. A spate of police killings of unarmed black men, recorded on smartphone cameras and disseminated via social media, gave rise to the Black Lives Matter movement, which brought widespread attention to the racial inequities of American law enforcement. The bitter resistance to Obama’s presidency punctured the belief that his election heralded a postracial America. And the political ascent of Donald Trump, who rose to prominence peddling a myth about Obama’s birthplace, represents a step backward in progress toward racial reconciliation.

As a result, Democrats of all races are far more “woke,” or alert to social and racial injustice, than ever before. And the candidates seeking to win their votes in next year’s primaries and caucuses have gotten the message. In 2020, Democratic presidential hopefuls are no longer running away from race. They’re running right at it.

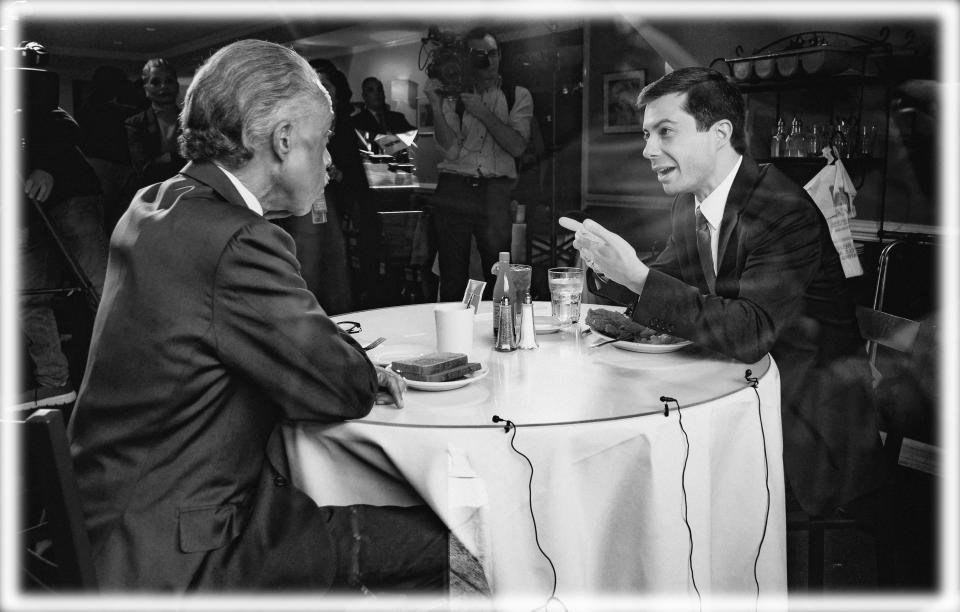

Black voters have long told pollsters they are concerned about systemic racism and discrimination, and are looking for candidates with real plans to address those issues. They still say that today. But while in the past, candidates may have addressed their concerns with symbolism, by appearing alongside Al Sharpton or being photographed eating at the famous Sylvia’s in Harlem, today’s Democratic candidates are increasingly relying on substance.

Perhaps the single clearest sign of this sea change came last month, when Pete Buttigieg, the very young, very white mayor of South Bend, Ind., released a multipronged plan to combat systemic racism in America by doing everything from “promoting black history and culture and ensuring Washington, D.C., statehood to tackling the racial wealth gap,” as Yahoo News’ Brittany Shepherd reported.

Buttigieg even wrapped his proposal in a neat rhetorical bow, naming it after the antislavery crusader Frederick Douglass and likening it to the Marshall Plan, which rebuilt Europe after World War II.

“We have lived in the shadow of systemic racism for too long,” Buttigieg said in a statement. “The Douglass Plan will help heal our deep racial divides with bold policies that match the scale of the crisis we face today.”

Buttigieg’s plan is indeed expansive. Its goal would be to “dismantle old systems and structures that inhibit prosperity and build new ones that will unlock the collective potential of Black America” across roughly seven sectors: health, education, criminal justice, business, housing, the environment and democracy itself. Its many provisions include a $25 billion investment in historically black colleges and universities and other minority-serving institutions; a fund to invest in minority-founded businesses and offer loan deferments and forgiveness programs to black college students who start businesses after graduating; reforms meant to cut incarceration rates by 50 percent by reducing arrests, decriminalizing drug possession, closing prisons, and investing in social services and diversion efforts; the restoration of the section of the Voting Rights Act voided by the Supreme Court in 2013; the abolition of the death penalty; and the use of federal funding to encourage police transparency.

But Buttigieg’s plan is not at all unique among 2020 candidates.

Released in May and named after Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice and civil rights icon who won the case of Brown v. Board of Education, Bernie Sanders’s education plan aims to combat discrimination and rectify school segregation above all else. According to a recent report, the average nonwhite school district receives $2,226 less in funding per student than the average white district. Under Sanders’s plan, a “national per-pupil spending floor” would be established, the local property-tax funding model would be reevaluated, and Title I funding, which has gone to districts with the highest percentages of poor children since 1965, would be tripled. Sanders would also ban for-profit charter schools and impose a moratorium on federal dollars for charter expansion until a national audit was conducted.

Likewise, other leading candidates have proposed plans that address systemic racism in ways that go beyond the now-standard Democratic box-checking of criminal justice reform and mass incarceration.

Kamala Harris has pledged to invest more than $70 billion in historically black colleges and universities and minority small businesses; spend $100 billion to help increase rates of minority homeownership; slash disproportionate black maternal mortality rates; legalize marijuana and foster minority involvement in the development of the industry; and provide tax credits and rent credits to low-earning families.

Elizabeth Warren has taken a similar approach, releasing a plan to close the racial wealth gap by issuing $7 billion in grants to entrepreneurs of color and including in her student-loan debt forgiveness proposal a $50 billion fund for historically black colleges and universities and other minority-serving institutions. “Black Americans were kept out of higher education, and federal and state governments poured money into colleges that served almost exclusively white students,” Warren told the Atlantic. “This is a chance for African American students to make choices on a level playing field about where they want to be in schools not driven by tuition costs.”

Under Cory Booker’s “baby bonds” plan, every newborn would receive a $1,000 savings account funded annually on a tiered basis, depending on family income; when the child turns 18, he or she would get a lump sum as large as $50,000, to be used for education, entrepreneurship or buying a home. According to the Center for American Progress, baby bonds would do more than any other current proposal to narrow the racial wealth gap. “It would be a dramatic change in our country to have low-income people break out of generational poverty,” Booker has said. “We could rapidly bring security into those families’ lives, and that is really exciting to me.”

Julián Castro’s “People First Policing” plan, released in June, focuses on ending “over-aggressive” and “racially discriminatory” policing by restricting when police officers can use deadly force, ending the “school-to-prison pipeline” and encouraging local governments to limit arrests to serious offenses. The former Housing and Urban Development secretary also has specific plans for eliminating lead exposure and reversing decades of housing discrimination. (Booker, Harris and Warren have similarly race-conscious housing plans; Warren has called hers the “first step to addressing the black-white wealth gap.”)

But perhaps no issue dramatizes the Democratic Party’s new thinking on systemic racism as much as reparations. Previously considered untouchable by most mainstream candidates, the idea of compensating black Americans through cash payments for the devastating economic legacy of slavery and segregation has become part of the primary conversation. Warren, Harris, Buttigieg, Castro and Booker have spoken positively about the idea, which the last two Democratic presidential nominees (Obama and Hillary Clinton) opposed. Booker has introduced a companion Senate bill to HR 40, the long-stymied House measure calling for the federal government to study reparations.

“We cannot address the institutional racism and white supremacy that has economically oppressed African-Americans for generations without first fully documenting the extent of the harms of slavery and its painful legacy,” Booker said in the statement. “It’s important that we right the wrongs of our nation’s most discriminatory policies, which halted the upward mobility of African-American communities.”

Among the bill’s 12 co-sponsors were fellow 2020 candidates Warren, Sanders, Harris, Amy Klobuchar and Kirsten Gillibrand.

None of them, however, has been as vocal as self-help guru Marianne Williamson, whose full-throated defense of the policy at the last Democratic debate went viral.

“We don’t need another commission to look at evidence,” she said. “There [were] 4 to 5 million slaves at the end of the Civil War. ... They were all promised 40 acres and a mule for every family of four. If you did the math today, that would be trillions of dollars, and I believe that anything less than $100 billion is an insult.”

The politics of race in America are always fraught — especially when they intersect with the politics of redistribution and government activism.

For instance, only 26 percent of Americans support the idea of slavery reparations. It would almost certainly become a Republican talking point against any Democrat who endorsed it.

The conventional wisdom would say that Democrats are running a risk by turning more broadly away from the race-blind economic policies of the past and toward 2020’s woke agenda. In this view, any attempt to combat systemic racism with proposals designed specifically to benefit black Americans will stoke further resentment among the white working-class voters who switched from Obama to Trump in 2016.

There are signs, however, that this kind of thinking is outdated. For starters, black voters — and particularly black female voters — will play a major role in this year’s primary battle. The most diverse field ever, with two prominent black candidates, Harris and Booker, competing against Joe Biden, who incessantly reminds voters that he was Obama’s running mate, ensures a heated battle for black voters. Part of the Democratic Party’s new race consciousness is just pure primary politics.

Yet the political logic of finally tackling systemic racism extends to the general election as well. Clinton lost in part because of those Obama-Trump voters. But she also lost because black turnout plummeted in key states such as Wisconsin and Michigan and many liberals opted for third-party candidates instead.

A bold “black agenda” could be a way to reverse both trends. According to Andrew Engelhardt, a political scientist at Brown whose recent work includes “Racial Attitudes Through a Partisan Lens” and “Trumped by Race: Explanations for Race’s Influence on Whites’ Votes in 2016,” “White Democrats’ average levels of racial resentment declined nearly 16 percentage points” between early 2016 and late 2018. As the New York Times’ Thomas Edsall recently explained, “This is by far the biggest attitudinal shift to the left — or the right, for that matter — in the last 30 years,” and it is “a reaction driven in large part by Trump’s race baiting.”

In other words, at a time when Trump’s latest offenses seem to transform every week into yet another fight over whether the president of the United States is, in fact, a racist, there may be worse ways to unite and motivate Democratic voters — black and white — than by declaring explicit war on the sentiments and the system that, to them, he represents.

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

FBI document warns conspiracy theories are a new domestic terrorism threat

Marianne Williamson on reparations and her emails with Oprah

'It's blasted across America': How Fox and Sean Hannity amplified a Russia-fueled conspiracy

Democrats resume search for a 'smoking gun' to bring down Trump

PHOTOS: Adorable twin cats showcase their fascinating eye colors