In the Trump era, Dems are searching for a way forward. Tom Perriello thinks he's cracked the code.

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. — Tom Perriello has rarely encountered a problem he didn’t think Tom Perriello could solve.

While still a student at Yale University, the former Virginia congressman and current Democratic candidate for governor made a vow, he says, to “never think about what I might want to do next and instead to listen to a sense of calling about where I’m supposed to be right now.”

In his 20s he embarked on a career in “justice entrepreneurship” — his term — trekking from continent to continent in search of “higher-risk, sometimes higher-physical-risk, efforts to make a difference in the world”: prosecuting warlords in Sierra Leone, consulting in Kosovo, launching a progressive Catholic nonprofit and an online activist network back in the States.

In his early 30s, frustrated by politicians with “too narrow a sense of what’s possible,” he decided to offer himself up as an alternative, leapfrogging the usual roster of rookie offices in favor of a 2008 challenge to six-term GOP incumbent Virgil Goode in Virginia’s solidly conservative Fifth Congressional District — a race Perriello won by that cycle’s skimpiest margin, a mere 727 votes.

Less than two weeks after leaving office — he couldn’t withstand the tea party wave of 2010 — Perriello rushed to Egypt to “find his way inside” Tahrir Square, then spent “a lot of that year there and around the Syrian border trying to understand the Arab Spring.” He went on to accept an even more challenging assignment from then-President Obama: brokering the first peaceful transfer of power in the history of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Now, at the ripe old age of 42, Tom Perriello thinks he can save the Democratic Party.

“We are trying a next-generation approach to Democratic politics,” Perriello told me as his SUV rolled past the bare oak trees that line Interstate 64 between Charlottesville and Richmond. “The hope is that we win the governor’s race and run the table in the legislature. If, in doing so, we create a blueprint for Democratic success in 2018, then that would be great. This could be the model that others emulate.”

***

If there’s one thing Democrats seem to agree on, it’s that they can’t keep doing what they did in 2014 and 2016. Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton. Republicans hung on to the Senate. The House, meanwhile, remains in GOP hands, as do 33 governor’s mansions and 32 statehouses — a record in recent years.

Could a candidate like Tom Perriello be the change that Democrats have been waiting for?

Aside from a few special elections, there are only two big contests to obsess over in 2017: the governors’ races in New Jersey and Virginia. Early on, they both seemed kind of sleepy. But then, in January, Perriello launched a surprise last-minute challenge to Virginia’s next-in-line Democratic nominee, Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam, and the entire political press corps descended, en masse, on the Old Dominion.

A couple of narrative threads have emerged. One is that the primary will pit a supposedly milquetoast Virginia centrist (Northam) against a bold progressive insurgent (Perriello) in a battle for the ideological soul of the Democratic Party. The other is that Northam represents the political establishment — every prominent Democrat in the commonwealth has endorsed him — while Perriello represents authentic outsider anger.

Both storylines liken Northam vs. Perriello to last year’s tussle between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, with Northam in the Clinton role and Perriello as Sanders. Both have some truth to them. And both seem A-OK with Perriello, who predicts that Northam’s establishment backing will be “a political curse with the voters” and made sure to remind me that his rival voted for George W. Bush not once, but twice.

“At the time, I didn’t pay much attention to politics,” Northam has said. “Knowing what I know now, I was wrong and would have voted differently.” His campaign also vehemently denies that he is a centrist, pointing to his strong liberal track record on gun safety and reproductive health as proof.

Yet as I discovered during my two days on the trail with him, the reality of Perriello’s “next-generation approach” is more nuanced — and more interesting — than the prevailing hot takes might suggest.

From an electoral standpoint, Democrats have two huge, and somewhat contradictory, problems. The first is finding a way to win back the almost 1 in 4 white working class voters who defected from the party last November; the second is motivating their base — Hispanics, black people, millennials, urban liberals — to show up and vote in nonpresidential elections.

Perriello’s promise is that he can fix both problems at the same time. And despite what he might say on the stump at the start of a Democratic primary, the solution isn’t as simple as running as a “proud progressive.”

When Perriello was in Congress, he wasn’t a member of the Blue Dog coalition (the gang of mostly Southern, mostly moderate Democrats who were mostly wiped out in 2010). But he resembled them in some ways. He cited moderates such as Jim Webb, Jon Tester, Mark Warner and Tim Kaine as models, and wound up ranking as the 15th most conservative Democrat in the House (of 258). He spoke of how his faith “helps sustain me through difficult times, shapes my commitment to service, and defines my belief that we will ultimately have to answer for how we have treated the least among us.” He received an A rating from the National Rifle Association, opposed an assault weapons ban and warned Obama that “to even consider reinstating [it] is an affront to our Founding Fathers, who so clearly understood the importance of the ordinary citizens’ right to keep and bear arms.” And in 2009, he voted for the Stupak Amendment, which would have prohibited insurance companies that participate in the Affordable Care Act’s exchanges from covering abortion.

The Democratic Party of 2017 is different from the Democratic Party of 2009, and running for governor is different than running for the House. Virginia has changed too — becoming “a much more diverse and accepting state,” as Perriello likes to say.

But the big difference is that today, everything in politics revolves around Donald Trump.

And so Perriello is making a bet that, in the Age of Trump, what Democrats basically need is a new breed of Blue Dog Democrat. Less conspicuous centrism, more colorbind populism. (The working class isn’t just white.) On the one hand, you rally the left by loudly opposing the president’s “hateful, toxic” agenda. On the other, you actually try to win back Trump voters. Not by emphasizing faith, or guns, or abortion, as your predecessors might have, but by focusing relentlessly on the economic anxieties that drove them to vote for the president — the same economic anxieties, incidentally, that drove many Democrats to vote for Sanders.

In a sense, then, Trump actually represents an opportunity for Democrats: to rile up the base by resisting him; to create a new working-class coalition by stealing his populist thunder.

“We need to have a walk-and-chew-gum strategy,” Perriello told me. “I was speaking passionately about issues of inequality, job loss and corruption of the system 10 years ago, when those weren’t necessarily the party’s mainstream talking points. This gives me credibility both with the base and with Trump voters.

“And that’s part of why I’m in the race,” he continued. “Too many Democrats believe a status quo-like message is going to be sufficient, when in fact if we’re not starting to talk about the crisis that’s emerging from automation and remonopolization of the economy, we should not be surprised if people are not that inclined to show up. When I go out and talk to people, this is what they’re talking about — whether it’s our base voters or Trump voters.”

With that, Perriello grinned. “So let me be clear,” he said. “I plan to win a lot of votes in red parts of the state. I’ve done it before.”

***

It’s a cool Thursday night in Charlottesville, the largest and most liberal city in Virginia’s sprawling, otherwise rural Fifth District. Perriello has returned to his old congressional stomping grounds for a town hall at the Haven, a church that’s been repurposed as a day shelter for the homeless.

This is the candidate’s comfort zone. Back in the summer of 2009, as Obama’s Affordable Care Act was winding its way through Congress and the vast majority of red-district Democrats were busy ducking outraged activists and concerned constituents, Perriello held 22 town halls, often fielding hostile questions for four or five hours at a time.

It’s also a clever bit of counterprogramming. The vote on the Republican bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act is scheduled for this day — the seventh anniversary, as it happens, of the day Obama signed Obamacare into law. The campaign has seized on the timing to remind Virginians that Perriello not only voted for the legislation but refused to run from his vote during election season, even though his district largely disagreed.

“Seven years ago, we gathered around the TV and watched with pride as, wearing my father’s suit, Tom went and cast his vote,” Perriello’s older sister, Paige, tells the audience. (She also points out that she’s a pediatrician, just like their dad, Vito, was.) “When Tom cast that vote, he was not worried about reelection. He was thinking about the children, like the ones I see every day, whose parents are struggling to find affordable health care while also putting food on table. Tom lost his seat in Congress after voting for the ACA, but hundreds of thousands of Virginians are better off.”

That, in a nutshell, is the Perriello brand. In 2007, he called it “conviction politics” and praised candidates — Webb, Kaine, Tester — who “spoke from a deep sense of right and wrong, not a desire to position themselves on an artificial spectrum of right, left, and center.” He even quoted country singer Toby Keith to explain what sort of congressman he aspired to be: “You may not like where I’m going, but you sure know where I stand / Hate me if you want to, love me if you can.” For Perriello, the ACA vote — as well as similarly challenging votes for cap-and-trade legislation and the DREAM Act — is proof that he succeeded.

As Paige finishes speaking, the crowd leaps to its feet. In the pew in front of me, a liberal woman named Kate glances at her husband, Jeff, a lifelong Republican; it’s almost as if she’s looking for permission. Jeff nods but stayed seated; Kate joins the standing ovation. “She’s a big supporter,” Jeff tells me. “I’m just here to listen.”

Soon the candidate takes the stage. He hasn’t changed much since he last ran for office: a little less baby fat, maybe — and a little less hair — but the square build, the collegiate voice and impatient energy are the same. He’s still a bachelor as well, which is part of the reason he can do things like hold a campaign event (or two) every hour for 24 hours straight.

One young woman — “born and raised in Blacksburg, Va.,” the site of the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting — asks Perriello to “articulate [his] position on gun control,” then breaks down crying. He explains that “those who have lost people have continued to push and push to change the politics [of guns] — and that includes with politicians like me.” (Elsewhere, Perriello has promised to restrict access to guns with “no defensible role in sport or home-defense” and said that the NRA, which he once called the “epitome of -people-powered politics,” has become a “nut-job extremist organization.”)

Another woman asks about abortion. “I had read that while you were in Congress you were labeled as a pro-life Democrat, and then, of course, recently you’ve come out as being pro-choice,” she says. “Can I expect consistency?” Perriello responds that while he’s always been pro-choice, he promised his constituents that he would vote against taxpayer-funded abortions — a promise he has since come to “regret” after learning that it would prevent “women of color and poor women” from having “access to that right.”

Despite these off-message moments, however, Perriello never loses his balance. He brings everything back to Trump and the working class. Anxiety about what’s happening on Capitol Hill pervades the predominantly Democratic crowd, but Perriello doesn’t frame the fight over Obamacare in terms of interparty warfare, and he doesn’t limit the fallout to millions of people losing their insurance. More than any Democrat I’ve heard, he talks about how your pocketbook will take a hit.

“There is a $600 billion tax cut for people making $1 million or more a year [in this bill] — a massive unpaid tax cut for millionaires and billionaires,” Perriello says. “But the real kicker, of course, is who picks up the tab: the middle class. Because what happens when 24 million people lose health insurance? They go back to the emergency room and catastrophic care. And how is that cost passed on? To middle class people in their premiums. Now, I’ve spent a lot of time in the more conservative parts of Virginia, and I haven’t found a county yet that considers that a winning formula for electoral success.”

As the crowd thins out, I reconnect with Jeff and Kate. Jeff, the Republican, says he likes what he heard. “I think we’ve gotten away from listening to people,” he tells me. “You’re elected to represent your constituency, not your party. It sounds to me like that’s what Perriello tries to do.”

***

The next morning, the candidate picks me up at the crack of dawn for the ride to Richmond, where he will be touring a low-income community health care center called the Daily Planet. On the way, we talk. Perriello has a lot to say: about Northam, about Ed Gillespie (the former lobbyist and Republican National Committee chair whose likely to win the GOP nomination), about why he will beat both of them; about how, as governor, he can serve as a firewall against both Virginia’s Republican legislature and the “circus ringleader” in chief.

But I’m most interested in policy — in whether Perriello can actually use his innate wonkiness to bring the base and at least some Trump voters together.

Perriello, of course, says yes.

“There are enormous opportunities for a new bipartisan approach,” he insists. “The conversation has shifted, and the existing political establishment in both parties is starting to catch up to that with baby steps, but the people are four steps ahead of where they are. With the right kind of politics, we can catch up to the people.”

“So what are some examples?” I ask.

“In talking to law enforcement people and the people who run our prison system, they feel like they’re being asked to be mental health providers of first resort, and they know it’s not their area of expertise,” he says. “So we have passed a tipping point in terms of interest across very diverse constituencies to address the mental health crisis.” Same goes for opioids and PTSD among veterans. “The legislature has been taking some positive steps,” Perriello explains, “but the people are ready for a bolder approach.”

Another obsession of Perriello’s is the ongoing remonopolization — “this consolidation, both geographically and sectorially” — of the economy.

“I was curious whether people would be responsive,” he says. “We’ve found that they are. They understand that the jobs have been leaving and moving into fewer and fewer ZIP codes and fewer and fewer companies, and in talking to people about solutions, there has been a lot of interest in ideas we would describe as radical localization. People like the idea of getting back to decentralized food production and energy production. This goes beyond the normal political lines.”

The list goes on. If Perriello were Bernie Sanders 2.0, he would be proposing free public college for everyone; instead, he thinks “the place we should prioritize are these alternate pathways, including apprenticeship programs, career and technical education and community college.”

“When we give a massive tax cut to the richest corporations in America, Republicans call it an investment that will ‘trickle down’ to the rest of us,” he says. “But when we talk about investing in human beings by making community college free, they call it a welfare or entitlement program. The second we start to realize that it’s the purchasing power of the working and middle class that drives growth is the moment we can start to build new coalitions.”

Likewise, Perriello’s decision to turn down donations from the statewide energy monopoly Dominion Power, a first for a major-party candidate, isn’t just about good governance. It’s also about how Virginia is “losing solar jobs to North Carolina and wind jobs to Maryland” as a result of the utility’s influence with both parties in Richmond,” and how “people in Virginia feel, particularly in communities of color and rural white communities, that they’ve been excluded from growth because of our broken and insular political system.”

Even redistricting, perhaps the least visceral of political issues, is a pocketbook concern for Perriello. Noting that the next governor will have the opportunity to undo a decade’s worth of GOP gerrymandering, he argues that “the radical district maps are why Virginia has a lower minimum wage than West Virginia, and why we have not been able to get universal pre-K. Virginia had been ranked in all these ways as the best place to do business, the best place to raise a family. We’ve moved down in those measures largely based on underinvesting in infrastructure and education — and the barrier to that is a legislature that doesn’t reflect the people.”

“I have found that connecting those dots has been extremely resonant on the trail,” he continues. “So if you are looking at things that the rest of the country can learn from Virginia, I believe we will make redistricting a significant electoral issue this year.”

With that, we arrive at the Daily Planet, and the candidate embarks on his tour. Before Perriello can implement any of his big ideas, he needs to win two elections: the primary and the general. Neither outcome is assured: Perriello and Northam are tied at 26 percent in the latest poll, and neither Democrat leads Gillespie in a hypothetical matchup. All of the Democratic delegates and state senators in Virginia have endorsed Northam, as have Sens. Warner and Kaine, both of whom are former governors. And as the Washington Post recently pointed out, “Northam has spent years building an army of loyalists across the state who can amplify his voice and do the single most important thing [in an off-year primary]: Get voters to show up at the polls.”

The rest of Perriello’s day, however, will only reinforce his belief that he’s the right man for the moment.

“I wouldn’t be running if Trump hadn’t won,” he told me earlier. “What that’s created, unfortunately, is a moment of deeply turbulent change. That change is either going to take the form of an unraveling of a lot of the core elements of our society — or it’s going to create a backlash that allows a more inclusive and progressive coalition to come forward and govern.”

After the Daily Planet, Perriello heads straight to Washington. Yesterday’s health care vote never happened; it’s been rescheduled for today. As Paul Ryan & Co. scramble in search of votes, Perriello makes a last-minute stop at a #KilltheBill rally at the Capitol. Moments before he steps to the podium, word arrives: The GOP has pulled its bill.

“I come with one simple message, which is that the resistance is working,” Perriello says; behind him, a protester waves a sign that reads, “Not Going Backwards.” “Obamacare has survived because of the organizing that people across America and across the commonwealth of Virginia have done. It has been the size of the crowds and the stories told that have made this building listen. We must figure out a way to sustain that. [But] what we know today is that we have the power to win.”

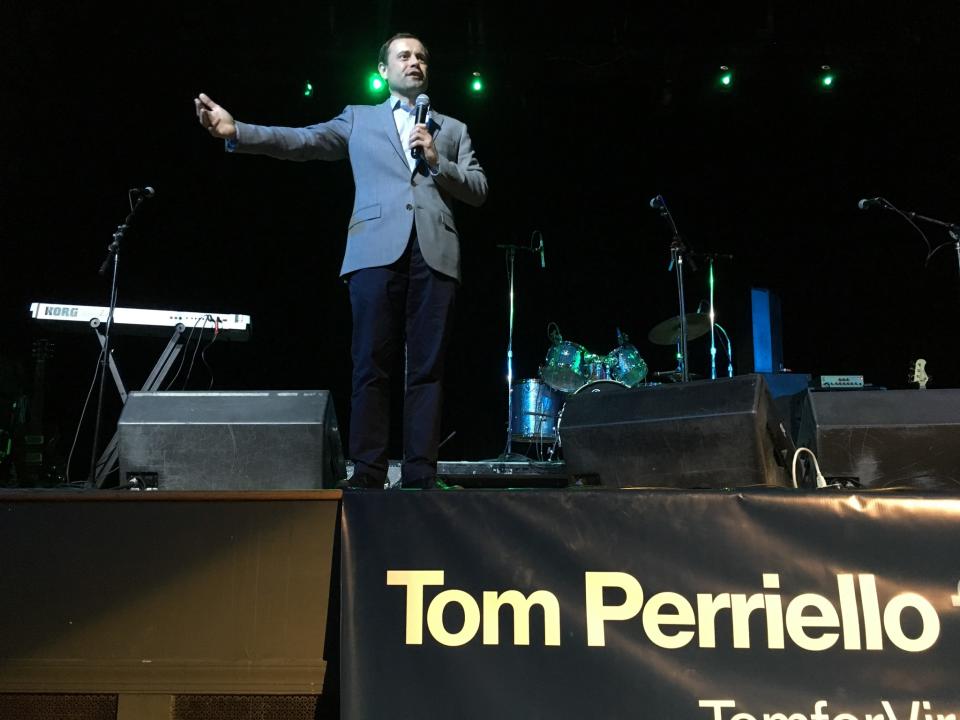

The campaign event scheduled for later that evening — a “Rock & Rally” at the historic State Theatre in Falls Church, Va. — was originally meant to be an entertaining Friday night fundraiser. But the Republican Party’s sudden implosion on Obamacare transforms it into something more significant.

“I decided to come 30 minutes ago,” Helen Li, a newly minted College of William & Mary graduate, tells me as we wait in a line that snakes around the block. “I was feeling so good about the health care fail that I thought, ‘Yay! I have to go celebrate.’”

As older liberals sit at tables in the back and younger hipster types sip $4 PBR, a diverse lineup of bands performs on stage: Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars, the D.C.-based Nag Champa Art Ensemble and the Perriello Pickers, a bluegrass ensemble founded specifically to support Perriello’s run. The symbolism about Virginia’s changing identity and economy is hard to miss.

About halfway through the show, Perriello takes the mic. He repeats his spiel about how the resistance is working; the crowd rejoices. But then he tells the story of an airport worker he recently met. Her name is Esther. She makes $14,000 a year. To support her three kids, she naps for an hour and a half on a bench, then heads to her second full-time job.

“When I asked what she wants, she says, ‘I want to see my kids awake once a week,’” Perriello recalls. “Esther is not going to vote for Ed Gillespie. The question is whether she’s going to vote. Is she going to take 45 minutes out of her day? In order to do so, she’s going to have to believe that there is a governor’s candidate who cares enough about her to wake up in the morning and not just check a box on raising the minimum wage, but to fight for it as urgently as we would fight for our own children.”

Perriello never mentions whether Esther is white or black, immigrant or native — and that’s kind of his point.

“Are we waking up in the morning with that passion?” he continues. “The good news is that when we do — when we run on that kind of bold, genuine growth strategy — then people will have our backs, [and] the very communities that Donald Trump’s team is trying to split apart will come together around the idea that finally there seems to be a candidate and a party that is fighting for them. That is what we are trying to do in this campaign.”

Read more from Yahoo News: