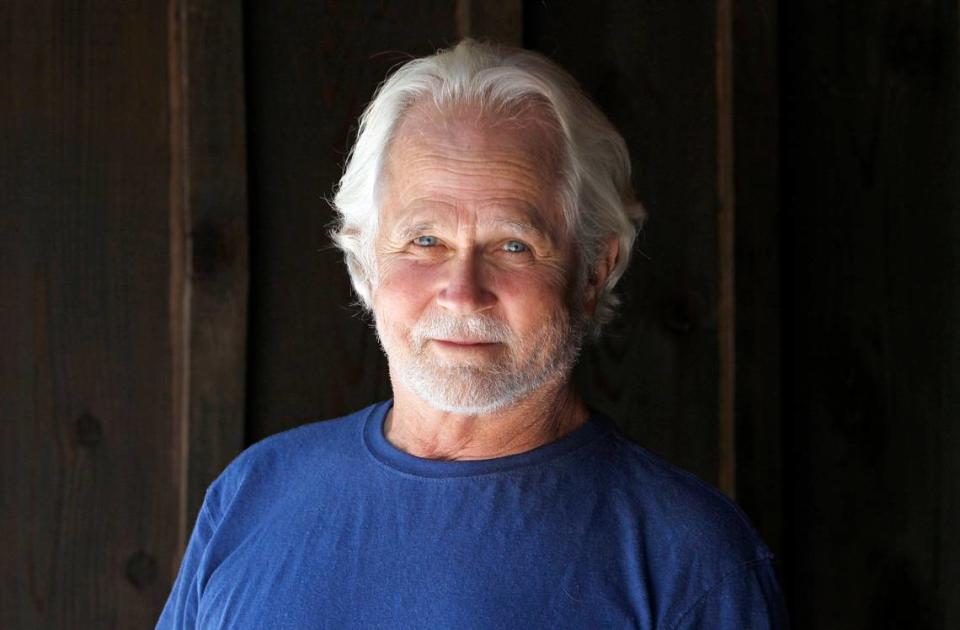

Tony Dow, aka Wally on ‘Leave It to Beaver,’ dies. He had strong ties to Kansas City

Tony Dow, the all-American big brother on the sitcom “Leave It to Beaver” who died Wednesday, had some strong Kansas City connections.

He met his wife, Lauren Shulkind, in 1979 while he was starring with Jerry “The Beaver” Mathers at the old Tiffany’s Attic dinner theater in Kansas City. They married in 1980.

Shulkind, who graduated from Shawnee Mission East High School, worked for Bernstein Rein Advertising at the time and cast Dow, best known as big brother Wally Cleaver, in a regional McDonald’s commercial.

“I was pretty thrilled that he would think that I was cool enough to want to be with me,” Shulkind told The Star in 2003. “With time, he just seemed to be a regular guy. It didn’t take long.

“But I will say, when we were kind of dating, one day I slipped up and called him ‘Wally.’ That was terrible.”

The couple occasionally visited her family in the Kansas City area.

In 1979, when Dow and Mathers were starring in “So Long, Stanley!” at the dinner theater, they stopped in at Winstead’s on the Country Club Plaza, according to The Star’s 2015 profile of longtime waitress Judy Eddingfield. Mathers was “talking with his hands” and knocked over a tray of double onion rings and shakes his server was carrying to the table, sending the food flying.

Said his on-screen brother: “Leave it to Beaver,” to the delight of the staff and diners.

Dow also starred at Tiffany’s Attic (a precursor to the New Theatre & Restaurant) in “Barefoot in the Park” and “Same Time Next Year” in 1978 and in “Come Blow Your Horn” (with “Beaver” mom Barbara Billingsley) in 1982. He also starred in “Lovers and Other Strangers” at the Waldo Astoria in 1984.

Dow, who endeared himself to millions of TV viewers, died at his home in Topanga, California. He was 77. The cause was complications from liver cancer, said his manager, Frank Bilotta. His managerial team incorrectly announced his death a day earlier, relying on erroneous family information.

“Leave It to Beaver,” airing from 1957 to 1963, depicted an idyllic suburban postwar American household and became a cultural touchstone of the baby boom generation. Hugh Beaumont was the handsome, ever-patient father, Ward Cleaver, and Billingsley played the understanding matriarch, June, who vacuumed in high heels and always tucked her boys into their beds.

With his light-brown hair, electric-blue eyes and the athletic build of a championship diver — which he was before joining the show — Dow was promoted as a teen heartthrob and received more than 1,000 fan letters a week at the sitcom’s peak. Years later, Mathers recalled Dow as much like his “cool” character: soft-spoken, suave and possessed of gymnastic skills that he showed off by walking up and down a flight of stairs on his hands.

Dow and Mathers toured in “So Long, Stanley!” for more than a year before Hollywood producers hired them and other surviving members of the original “Leave It to Beaver” cast — Beaumont had died in 1982 — for a 1983 CBS-TV movie reunion, “Still the Beaver.”

The program was a ratings smash and spawned two sitcoms, notably “The New Leave It to Beaver” on Ted Turner’s superstation, WTBS, from 1986 to 1989.

After the original “Leave It to Beaver” ended, Dow studied painting and psychology at UCLA, played dramatic and comedic guest parts on TV series, and appeared on a daytime teenage soap opera called “Never Too Young.” But after he joined the National Guard in the mid-1960s, he said, his career stalled. Not knowing when he might be ordered to report for active duty made it almost impossible to make acting commitments.

For years, he lived on a boat, made sculptures and survived on income earned primarily by running a construction business. Despite the perpetual airplay of “Leave It to Beaver,” Dow did not grow wealthy from the show. Because of a contract stipulation, he received residual payments for only four years after the sitcom went into syndication.

Beginning in his 20s, he said, he began a long and gradual descent into clinical depression.

“I’d say inheritance had more to do with it than acting,” he told the Chicago Tribune. “It was an illness prevalent on my mother’s side of the family. But certainly ‘Leave It to Beaver’ had something to do with it. Certainly it had something to do with raising one’s expectations and establishing a certain criteria that you would expect to continue in life.”

Attempts to get back into acting only exacerbated his dark moods. He had played killers, single fathers and lawmen on other shows, but casting agents could not overcome their perception of him as clean-cut and earnest Wally.

That so few people talked openly of depression complicated his private struggle, he said, and for years, he could not find ways to manage what he called a “self-absorbing feeling of worthlessness, of hopelessness.”

He was nearing 40 before he began to stabilize, thanks to what he called a major improvement in drug treatments. In frequent speeches on mental health, Dow noted that he was “just one of millions” who have depression. “If Wally Cleaver can be depressed,” he said, “anybody can be.”

Turning away from acting to focus on other art forms helped. He had modest success as a sculptor, with work appearing in galleries and international exhibitions. Dow also began a career as a TV director, and his credits included episodes of “Babylon 5″ and “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.”

But he was always Wally to fans.

“I could never understand the reaction that Jerry or I would get from people,“ Dow told The Star in 2003. ”Then I was on a plane once and I walked by this guy, and he looked really familiar to me. I asked a stewardess, ‘Who’s that guy?’ And she said, ‘Oh, that’s (Harlem Globetrotter) Meadowlark Lemon.’ And the biggest smile came across my face.

“All of a sudden I realized what it is. I mean, I don’t know what it is — but it happened to me. I just got that warm feeling and smiled and thought, ‘You know, that’s really cool.’”

Includes reporting by The Washington Post and The Star’s Dan Kelly.