Treatment or enforcement? Record fentanyl deaths spark new debate over war on drugs

John Koch walked down 27th Avenue in northwest Phoenix, a street littered with crumpled burnt foils used for smoking fentanyl. Nearby, people slumped on the curb, their nervous systems overtaken by the powerful drug. Others called out: "We got blues and shards" – street names for fentanyl-laced opioids and methamphetamines.

Carrying his backpack filled with NARCAN, a nasal spray used to treat opioid overdoses, Koch, 33, an outreach worker, was there to warn them: Take even a small amount of fentanyl and you could die.

About 1,000 miles away on the U.S.-Mexico border, a team of U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers huddled in a trailer and stared at rows of monitors showing images of the inside of cargo areas of semitrucks just outside. They were looking for signs of fentanyl – or any drug – being smuggled into the United States as part of a multimillion-dollar effort to upgrade technology along the border and stop fentanyl from reaching American households.

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention counted more than 100,000 overdose deaths across the United States last year – the most it has ever recorded. Nearly two-thirds of those are estimated to be fentanyl-related.

The soaring death toll is once again stirring fierce debate about the best way to end the United States' decadeslong drug crisis: Continue to invest in the half-century-old war on drugsthat prioritizes enforcement? Or increase focus on harm-reduction programs that emphasize clean needles and education to users?

Critics of enforcement policies argue public health approaches that punish people with substance use disorders do not make them quit. Opponents of harm reduction models say government dollars shouldn’t be spent on allowing people to use drugs.

The debate has never been more urgent, with fentanyl now cheaper, more potent and more widespread than ever as Mexican cartels have become the single biggest supplier of the deadly drug.

“We are seeing a staggering amount of fentanyl in the United States,” Drug Enforcement Administration chief Anne Milgram told USA TODAY.

Dr. Rahul Gupta, director of the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy, warned the surge of fentanyl is reaching an all-time high.

"This is a very historic time,” he said. “We have never had the amount of death and destruction that we're seeing now.”

Fentanyl fueling next wave of opioid crisis

Illicit fentanyl – produced mostly in foreign clandestine laboratories and trafficked into the United States in powder and pill form – once ravaged predominantly white suburbs as an alternative to heroin or other opioids, experts say. But increasingly the drug is showing up in urban centers, from Los Angeles to Phoenix to New York City.

People of color are dying at faster rates than white users. Overdose mortality per capita among non-Hispanic Blacks more than tripled from 2010 to 2019, compared with a 58% increase among non-Hispanic whites, according to a study published in February in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

In some cases, users experiment with cocaine or other drugs inadvertently mixed with fentanyl. Others knowingly use fentanyl for its cheap, powerful high – but are unaware of the drug’s potency.

The pills, stamped with an "M" on one side and "30" on the other, are designed to look identical to legitimate prescription drugs such as Oxycontin, Percocet and Xanax – but have enough fentanyl for three people.

“It's 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine,” said Mark Lippa, acting deputy special agent in charge for Homeland Security Investigations in the Rio Grande Valley. “Just 1 kilogram of this fentanyl can potentially kill 500,000 people.”

On average, prices are $3 to $10 a pill – but in some cities across the country, people can get pills for as little as $1 each.

"All of a sudden, what used to be a $150-a-day heroin habit has become a $15-a-day habit," said Koch, director of community engagement at Community Medical Services in Phoenix. "It’s a habit that can be very sustainable."

To try to push back the surge of fentanyl, DEA officials pored over CDC and FBI data and deployed agents to 34 cities across 23 states – from Oakland, California, to Miami. Launched last month, Operation Overdrive uses the data to target criminal drug networks in areas with the highest rates of drug-related violence and overdoses, Milgram said.

Fentanyl’s compact size and rampancy make it challenging to wipe out, she said. About 4 in 10 illicit pills today contain fentanyl, up from 2 in 10 just a few years ago, Milgram said.

“It is a completely different world, a completely different threat, from plant-based drugs,” such as heroin and cocaine, she said.

Harm reduction can save lives

On a recent Tuesday morning on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Shantae Owens, who lost his 18-year-old son to an opioid overdose in 2019, passed out fentanyl test strips to people and talked to them about overdose prevention centers. In December, New York opened the first two clinics in the country that provide substance users a monitored place to safely inject.

For Owens, 48, things have changed a lot since he was a heroin user 15 years ago while living on the streets of New York City.

"Back then the only options we had was prison or inpatient treatment," said Owens, a harm reduction community worker with Vocal-NY, a statewide grassroots organization that advocates for low-income people directly affected by the war on drugs and mass incarceration.

More recently, the federal government, states and cities have treated substance use disorder as a public health crisis.

President Joe Bidenhas made harm reduction a key part of his fight against the opioid crisis. In his State of the Union address, Biden pointed to increased funding for prevention and harm reduction, while also pursuing drug traffickers, as solutions to the opioid crisis.

“If you’re suffering from addiction, know you are not alone,” said Biden, whose son Hunter Biden has been treated for drug and alcohol substance use disorder. “I believe in recovery, and I celebrate the 23 million Americans in recovery.”

Biden's proposed budget, released this week, calls for $42.5 billion for drug control programs, a $3.2 billion increase from current funding levels. This year, a historic 57% of funds were allocated to reduction programs including evidence-based treatment, harm reduction, prevention and recovery services, according to the White House. And, for the first time ever, 10% of the $3.5 billion earmarked for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration would be set aside for recovery services, helping people who have historically been unable to access care.

The proposed budget also requests an increase of $336 million for DEA investigations, diversion control and other counterdrug efforts, as well as an increase of $293 million for CBP to stop drugs from entering the country at the border.

Meanwhile, the Justice Department has said it is evaluating other policies and has signaled it might allow the opening of more supervised safety injection sites across the country.

"The point is that we are trying to make sure that, when it comes to saving lives, your ZIP code doesn't decide whether you get to live," said Gupta, the White House drug policy czar.

Studies have shown that "harm reduction" approaches, which prioritize keeping people with substance use disorders safe rather than persuading them to abstain, have greater results in long-term recovery. Some measures include opening syringe exchange programs, disbursing fentanyl testing strips and increasing the availability of naloxone and medically assisted treatment.

"Harm reduction is evidence-based medicine. It is one of our most powerful public health tools,” said Dr. Hansel Tookes, an infectious disease physician at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and founder of IDEA Exchange, the first legal syringe exchange program in Florida. “This is science. Moral outrage does not trump science."

A key challenge faced by advocates is making harm-reduction techniques available to people of color, who have been historically disproportionately targeted and incarcerated for drug offenses.

An inordinate amount of people of color are uninsured, leaving them unable to pay out of pocket for rehabilitative services, which are as expensive as a year of college tuition. And researchers have found that Black patients are significantly less likely than white patients to receive lifesaving medications for opioid use disorder.

“The primary barrier to health care among people living with substance use and mental health disorders is access, something that is exacerbated by social stigmatization, racism and policies," said Alex Kral, an epidemiologist specializing in drug use with RTI International, a North Carolina independent nonprofit research institute.

Harm reduction policies remain unpopular among many conservatives, who argue enabling users only deepens the problem.

Sens. Marco Rubio R-Fla., and Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., introduced a bill in February that would bar federal funding from programs that distribute items such as crack pipes or needles for illicit drugs.

“We need to do more but sending drug paraphernalia to addicts is not the answer,” Rubio said in a statement.

The outcry followed the announcement by the Department of Health and Human Services to spend $30 million in federal grants on harm reduction initiatives including "safe smoking kits." The kits typically include a rubber mouthpiece and disinfectant wipes intended to curb oral infections among users that share drugs.

In a letter to Biden last month, U.S. Rep. Bryan Steil, R-Wis., and 116 other Republican lawmakers blamed the White House for allowing the spread of fentanyl across the U.S.-Mexico border and urged Biden to stem the drug's spread.

Stopping fentanyl at the border

For U.S. authorities, a key tactic in the fight against fentanyl is stopping it from entering the country in the first place.

Since at least 2019, groups such as the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have increased their supply of fentanyl to the United States while direct shipments of the drug from China to the U.S. has decreased substantially, according to the DEA’s latest National Drug Threat Assessment. The fentanyl pills are increasingly referred to on the streets as “Mexican Oxy” or “M30s,” the report concluded.

Last year, Customs and Border Protection officers at eight South Texas ports of entry – from Brownsville to Del Rio – reported a 1,066% increase in fentanyl seizures. Overall, fentanyl seizures along the U.S.-Mexico border have skyrocketed, from 596 in fiscal year 2016 to 11,201 last fiscal year, according to the agency's statistics.

As cartel leaders realized fentanyl offered high profits at lower risk compared with cocaine and heroin, they amped up production, mixing the drug themselves rather than import finished fentanyl, said Ricardo Márquez Blas, a Mexico City-based security consultant. Today, the cartels produce enough fentanyl to supply the entire U.S. market, he said.

Mexican authorities have struggled to stop them because local law enforcement officials are not equipped or trained to root out small labs mixing small amounts of drugs, Márquez said. Even handing over control of border crossings and seaports to the military, which the government began doing in 2020, has not stopped the flow of precursor ingredients into Mexico, he said.

“The production of fentanyl has been growing these past few years and will continue to grow because the precursor ingredients keep arriving,” Márquez said.

U.S. officials have answered with a surge of money to upgrade technology at the border.

On a recent afternoon at the World Trade Bridge at the Laredo port of entry, one of the busiest overland crossings in North America, lines of trailer trucks stretched for more than a mile as they inched from Nuevo Laredo, across the bridge spanning the Rio Grande, into Laredo, Texas.

The border city is a key battlefront in the United States’ fentanyl fight. Last fiscal year, Customs and Border Protection officers in the Laredo sector confiscated about 588 pounds of the synthetic drug – up from just 50 pounds the year before, the agency said.

At the bridge, a handful of trucks at a time were redirected to a temporary hangar. They slowly drove through enormous scanners as seven officers inside a nearby trailer stared at rows of flat-screen monitors that showed the inside, undercarriage and roofs of the trucks. They were looking for irregularities – an out-of-place crate, a false side inside a trailer – that could point them to traffickers.

The agents were testing out “multi-energy portals,” a new scanning technology that allows agents to scan trailer trucks without drivers having to leave the cabs, said Albert Flores, the Customs and Border Protection port director for the Laredo Port of Entry.

If the system is approved, officials will build a 12,000-square-foot state-of-the-art control center where 24 officers will constantly scan trucks crossing the bridge. The initiative would increase the percentage of trucks being screened from 15% to 90%. The more trucks checked, the more drugs discovered, Flores said.

“It’s going to be huge for us,” he said.

Flores conceded that the scanners have limitations, largely because drug cartels always try to find ways to circumvent new tactics.

“They’ll adapt,” he said. “We figure it out. And then, before you know it, they’ll change it on us.”

Despite the efforts at the border, the drug continues to seep into the United States, raising concerns from local law enforcement departments that often have to deal with any fallout.

Overdoses in Pima County, Arizona, one of the epicenters for fentanyl overdoses of people of color, climbed from 337 in 2019 to more than 500 last year, said Tucson Police Assistant Chief Kevin Hall. The majority of those are opioid- or fentanyl-related, he said.

Investigators target large-scale, cartel-related drug rings in the region, Hall said. But most users stopped by police are given the option of medical-assisted treatment or jail in an initiative known as the Deflection Program. If an arrestee chooses treatment, charges are dropped and they don’t even have to finish their full treatment, he said.

“Coerced treatment doesn’t work,” Hall said. “We realize substance abuse is a chronic relapsing disease. This allows us to go back and reengage again and again. More often than not, it’ll be two or three or four times.”

Since launching in 2018, the program has deflected more than 2,200 people away from jail and into treatment, and about 36% of participants have completed treatment. The initiative started as a way to address a growing opioid crisis, Hall said. But these days, it consists almost entirely of fentanyl users.

“Now, everything we see is fentanyl,” he said.

Overdoses are soaring

The soaring number of drug deaths comes as communities have struggled with the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic fallout.

Tera Wise, a manager at Community Medical Services in Columbus, said her clinic has noticed a worrying trend in central and northern Ohio: previously incarcerated inmates, most of them people of color, overdosing on fentanyl soon after their release.

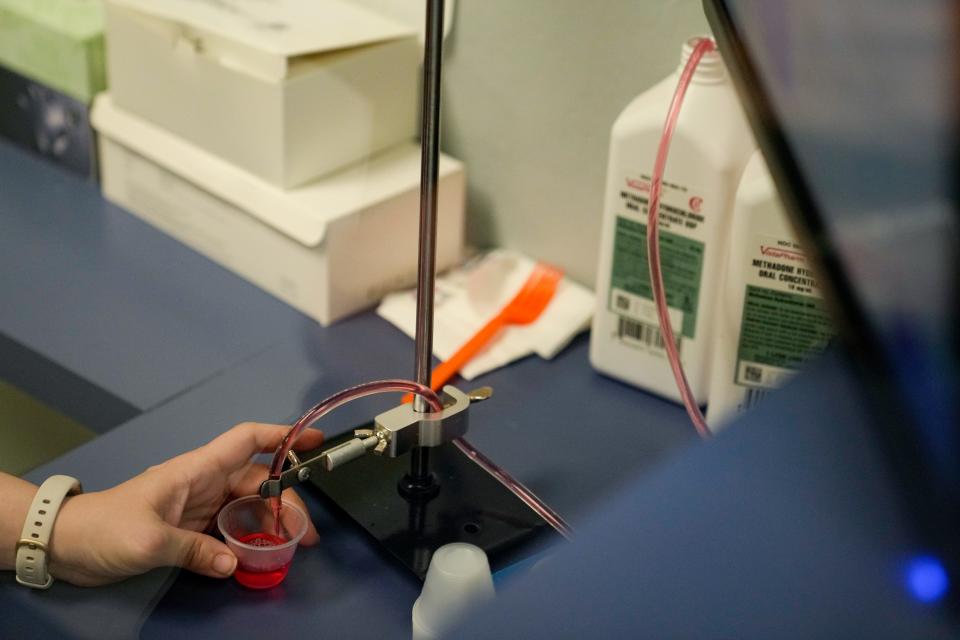

To combat the trend, her group recently launched an initiative of medical-treatment therapy inside four state prisons in Ohio. The goal is to try to ease the inmates’ substance abuse problems before they’re released, Wise said. Inmates are treated with a variety of medications, including methadone and buprenorphine, while attending counseling for underlying issues.

“We know there are still drugs in prison,” Wise said. “We really want people to be safe.”

For Suzanne Plymale, a peer support specialist at the Columbus clinic, a key tactic is sharing her story with those struggling with addiction. Her struggles began with prescribed benzodiazepines and shifted to Valiums and Xanax before escalating to hydrocodone and, ultimately, injecting black-tar heroin and fentanyl -- a disorder that consumed 26 years of her life. After entering recovery in 2017, she turned her attention to helping others.

Her story helps her connect with users, Plymale said.

"You need to really listen to people who are in the trenches, be compassionate and not paint folks with a broad brush," she said. "There’s no way we can enforce our way out of this problem."

Karla Norzagaray, a peer counselor in Tucson, Arizona, who has been in recovery for two years, said she's seeing many construction and landscaping workers struggling with opioid addiction. They are often injured on the job or suffer from chronic pain but don't have access to medical care in the first place. They go out and buy "blues" because they think they are buying medication on the black market.

As a case manager, she is responsible for closing out files of people who have sought treatment but then vanished for more than 30 days. Norzagaray said the epidemic has gotten so bad she's averaging closing 45 cases a week.

"I keep wondering, ‘Will this be the day I call and the person is dead,’" Norzagaray said.

In Tucson, Imyssia Mesa and Jovan Pe?a are the lucky ones: They got out. The pair have been in recovery from opioid use disorder for three years.

For Pe?a, 35, his use began as he coped with the grief of losing his ex-fiance, who died from an accidental fentanyl overdose. Mesa, 26, a survivor of intimate partner violence from a previous relationship, began buying fentanyl on the street to treat her pain from her often broken ribs and broken bones.

They said they are fortunate to have entered medically assisted treatment right before the pandemic when Mesa became pregnant with their baby.

But the fentanyl crisis has increasingly ravaged their neighborhood, with more people falling prey to addiction. It’s everywhere, Pe?a said, even at the bus stop, whereusers can be seen hunched over on the street, fentanyl seizing their systems.

Over the past year, the couple have lost four people to lethal overdoses.

"It's starting to look like one of these zombie apocalypse movies,” Mesa said. “It's sad.”

Follow USA TODAY national correspondents @RominaAdi and @MrRJervis on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: As fentanyl deaths soar, treatment versus enforcement debate heats up