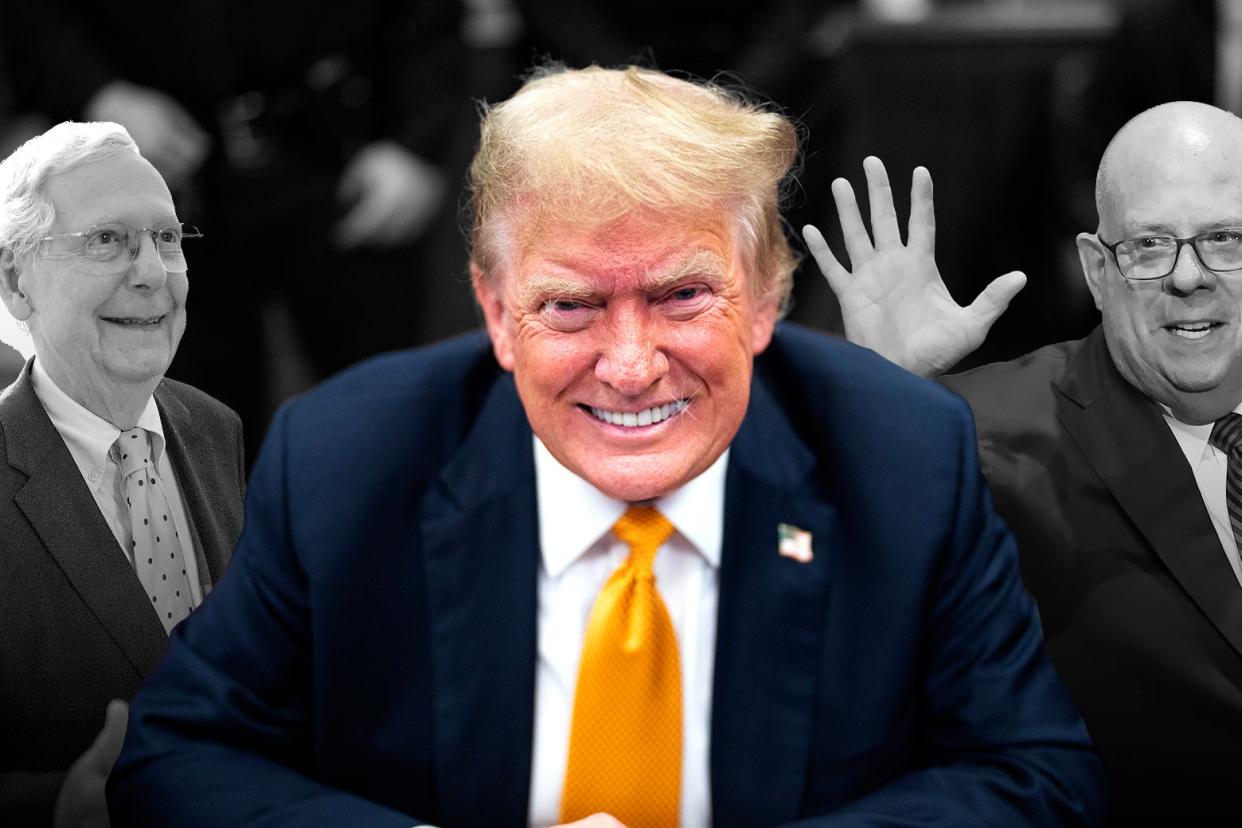

Trump Is Actually Being Nice to Some Critics. There’s Only One Explanation.

Something unusual happened last week when former President Donald Trump visited Capitol Hill for the first time since the Jan. 6 riots. Despite getting some of his first face time in years with various Republican doubters, haters, and resisters to the Trump cause, Trump was congenial toward them. He actually overlooked negative things that people had said about him in the past, or feel in the present, to appear conciliatory. His id was kept in check. This has never happened before.

What the hell is going on?

Trump made visits to both House and Senate Republican gatherings last Thursday. (Neither was in the Capitol building itself, but just off-campus at party retreats where politics could be discussed more freely.) In the House meeting, he made a peace offering to California Rep. David Valadao, one of the two remaining House Republicans who’d voted to impeach Trump. No such peace offerings were on the table during the 2022 primaries. He endorsed Florida Rep. Laurel Lee, too, a privilege not previously granted to members of Congress who’d endorsed Ron DeSantis in the presidential primary. He congratulated South Carolina Rep. Nancy Mace, a former enemy whom he’d tried to take out in 2022, on her recent primary win. He joked around with Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, who’d recently directly defied his wishes by moving to oust Mike Johnson as House speaker. Greene nearly swooned recollecting the interaction in an interview afterward.

On the Senate side, where there’s a much higher percentage of Republicans who’ve spoken out against Trump, things were also eerily peachy. The most notable Senate Republican to have broken with Trump, Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, shook hands with the guy a few times in their first time speaking since 2020. According to one senator who spoke to the Hill, Trump absolved McConnell of any blame in Senate Republicans’ poor 2022 midterms showing, and told him that “you’ve always worked really hard to increase the number of [Senate] Republicans.” Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, who still hates Trump, was right there in the meeting—right there!—and Trump did not make a single dig about what a loser he is.

Later in the day, he signaled support for Larry Hogan—another prominent anti-Trump Republican—in his race for Maryland Senate. The cynical, though certainly possible, take is that Trump was trying to damn Hogan’s chances in a deep-blue state by embracing him. But there’s little detectable cheek in his specific verbiage. He seemed unusually interested in the utility of winning an additional Senate seat, even if the victor would win that seat by keeping his distance from Trump.

“I’d like to see him win,” Trump said of Hogan. “I think he has a good chance to win. I would like to see him win. And we’ve got to take the majority.”

Where is the Trump that roots for “disloyal” Republicans to lose, in contravention to his own political interests? Was there nothing racist to say about McConnell’s wife? How did Romney enter and exit that room without getting noogied?

This is the continuation of a trend I noted a couple of months ago in which Trump, now that he’s on the ballot, is campaigning on a more pragmatic course for the party than he did as a chaos agent during the 2022 cycle. (As I noted then, too, this does not mean that he will govern pragmatically.) That means urging the party to tone down its more rigid beliefs on abortion and in vitro fertilization; endorsing more electable Senate candidates in swing states; and calling on the House Republicans—and Marjorie Taylor Greene—to cut it out with their ceaseless dysfunctional drama for a few months.

While Trump was suddenly insisting that others cut out the funny business and stay strictly on message about the border and inflation, he had not yet applied that rule to himself. And he still made his fair share of unintended news during his visit with House Republicans. A Trump comment about how Milwaukee, the host site to the Republican National Convention and the biggest city in a determinative swing state, is a “horrible city” was more of the Trump to which we’re accustomed.

But on the whole, the focus of this Trump campaign, relative to any of the previous campaigns Trump has run, or any of the midterm elections he’s meddled in, is unmistakable. Think about the inside-the-campaign drama from previous cycles, and the faucet of daily stories about staff anarchy and failed efforts to control the candidate. People like Corey Lewandowski, Steve Bannon, Kellyanne Conway, Paul Manafort, Brad Parscale, and Bill Stepien became household names for their roles in overseeing the ramshackle Trump operation, the “strategy” for which was determined by whatever the candidate had on his mind at any given moment. This year, there’s little news from inside the Trump campaign, and no one outside of politics addicts knows who Susie Wiles and Chris LaCivita are.

The Trump campaign can’t be disciplined without the cooperation of the candidate, though. Neither Wiles nor LaCivita can force Trump to be civil with McConnell or Romney or Valadao, or to buy into the idea of uniting MAGA and non-MAGA blocs of the party, if Trump doesn’t want to. So why does Trump want to run a more disciplined campaign, with more minimized distractions, where he doesn’t pursue each of his impulses for retribution and self-defeating publicity to his heart’s delight?

It’s hard to see it as anything other than: Avoiding potential jail time has a way of focusing even the most untamable of minds.