When Trump made a pass at me. And why it matters.

This is a story about how Donald Trump made a pass at me. And about what that does and does not mean as he runs for president.

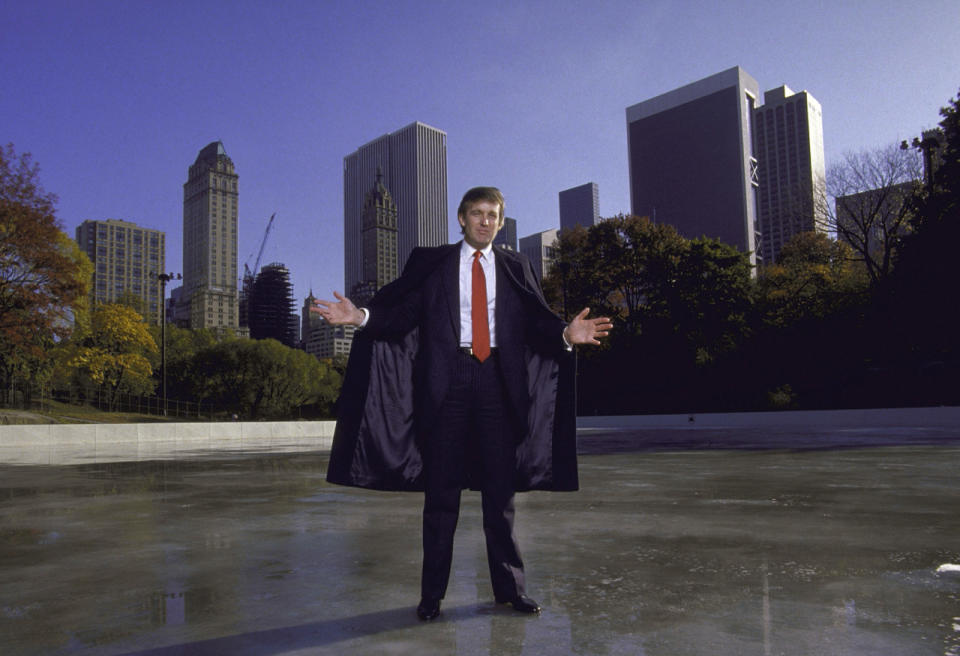

In the early months of 1987, I was a 26-year-old reporter at the New York Times and I went to a party at the newly opened Wollman Rink in Central Park. The rink had been rebuilt with great fanfare by Trump, who, remarkably, accomplished in four months what the city had been trying to do for nine years.

I had interviewed Trump once for an article and was somehow invited to this event, which I attended with my now husband. I introduced him to Trump, we all chatted briefly, and then Bruce went off to get some hot chocolate or somesuch. After he’d walked away, Trump said there would be an even better afterparty and I was welcome to join him, but only if I came alone.

That memory has surfaced periodically over the past few months as the Trump nomination has gone from unimaginable to unstoppable. I kept it mostly to myself for nearly all of that time, even as I wrote about Trump’s relationships with the women who worked with and for him over the years, and even as my article concluded — to my own surprise, frankly — that Trump had a record of promoting women to high-level jobs within his organization and of treating them (for better or worse) just like he treated the men. In retrospect, I think perhaps I should have disclosed that encounter when the story was published, but at the time, I thought of it as just one long-ago data point.

This weekend, when the New York Times ran its front-page story about similar memories of dozens of other women, I posted a brief recap of my own experience on my Facebook page. My point — my single encounter was part of a trend. By the next day, that Times story had come under fire because the woman in its lead anecdote said she’d been misrepresented, and I came to see my own encounter as one bit of pushback against Trump’s Twitter claims that everything in the Times article was ancient history, irrelevant, or a lie.

What then does Trump’s behavior — in and out of the workplace — mean for this election?

Let’s start with the indisputable fact that Trump objectifies women. I’m not sure why we are even debating that anymore. It is clear that looks matter to him and that his own virility is important to his sense of who he is. This was evident well before the Times story — from years of Trump commenting on which women were a 10 and which ones were hot enough for him to sleep with; from years of insults about women’s looks, everyone from Rosie O’Donnell to Carly Fiorina; from his own reassurances on the campaign trail that his genitalia were of acceptable size.

And it is also undeniably true that Trump has proudly employed women in positions of power over the decades. Back in October, I wrote about the triumvirate of women who ran major pieces of the Trump Organization in the 1980s, and of his boasts back then that he gave women authority in an industry that did not. His pride extends forward to the present, where he claims there are more women in executive positions in his company today than men.

So how to reconcile the two? The Trump who objectifies and the Trump that promotes? The man himself might lean toward F. Scott Fitzgerald’s quip that “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

But scholars would point out that Fitzgerald was likely being glib and meant exactly the opposite.

More simply, the disconnect probably reveals that Trump, like most of the rest of us, is a contradiction and a paradox. He compartmentalizes, and he also overflows. There are tinges of sexism in the stories of how he championed women at work (such as the time he refused to be seen dining alone with an “ugly” female business associate and asked a “better looking” one to join the lunch) and hints of feminism in his leering (like his clear pride in the business savvy of his daughter, Ivanka, even while noting if she “weren’t my daughter, perhaps I would be dating her.”

So is this mashup of mindsets relevant to Trump’s suitability as president? Of course, it is. The argument to the contrary — which comes down to “but everyone from Jack Kennedy to Bill Clinton ‘cherished’ women” — is specious. Yes, other leaders have had problems with women. And yes, that mattered. Perhaps the best evidence of how deeply it mattered — how serial predatory behavior particularly stained the Clinton legacy and his ability to govern — is the fact that Trump keeps bringing it up.

The way he does so — an I’m-rubber-you’re-glue approach to bad behavior around women — has a few weak spots, however. First, two clear wrongs don’t make anything right. Second, Bill Clinton is not running for president. And, finally, times have changed. What Bill Clinton did was clearly unacceptable at the time, but it is even less acceptable now, an ironic legacy of his behavior. Trump clearly recognizes the power of the changed lens and the effectiveness of labeling Hillary Clinton’s actions, which looked like that of a hurt wife back then as “enabling” and “victim blaming” today. Things look different decades later.

What makes Trump’s past actions fair fodder for current debate, therefore, is that he has not changed his lens on himself. In real time, I found his smirking pass to be a little smarmy — and not something I ever mentioned to anyone but my husband because it felt a bit like my fault. I was still proving myself in the still macho world of the New York Times, and I was pretty sure this sort of thing didn’t happen to my male colleagues. But I would not have labeled it predatory or harassing because those words were not in my contemporaneous vocabulary. I believe (but admit I can’t know for sure) that I would have responded differently today. Called him out for his actions. Certainly spread the story back at the office.

I suspect that’s what happened with Rowanne Brewer Lane too. Her experience was included in the lede anecdote in the Sunday New York Times story — about how she visited Mar-a-Lago in 1990, how Trump suggested she don a swimsuit and join him by the pool, then offered a selection of bikinis and paraded her around in one saying, ‘That is a stunning Trump girl, isn’t it?’ ” She has since said she didn’t feel “demeaned” or “offended” by this, and Trump has used that to call the entire story a “fraud.” But Brewer Lane has not disputed the facts: that a man she barely knew told her to put on a bikini and then showed her off. That she says she didn’t mind at the time doesn’t mean he had the right to act that way; all it means is that in the context of the times, she didn’t realize that.

Which raises the eternal question of whether we can hold actions of the past to standards of the present. Politicians regularly do so when it is convenient: The old sins of their opponents are permanent, while their own are merely a reflection of the times. The only real measure, though, should be whether, and how, a would-be leader has changed. Who has recognized wrong behavior, and who has stayed pretty much the same?

When past actions reveal continuity and predict future behavior, they are fair game. And when those ongoing attitudes give permission to others to voice their own misogynistic views (check the comments sections of articles about Rowanne Brewer Lane from the past few days — or, I’m betting, the comments on this article — for evidence), then it becomes our obligation to speak out.

Trump did not answer my query to his office asking whether he remembered our interaction 29 years ago, but late Wednesday, he sent out a tweet that read: “Some low-life journalist claims that I ‘made a pass’ at her 29 years ago. Never happened! Like the @nytimes story which has become a joke!”

Today, Trump’s daughter, Ivanka, assured us on “CBS This Morning” that her father is “not a groper.” That (coupled with his wife Melania’s assurance to DuJour magazine a day earlier that her husband is “not Hitler”) highlights rather than mitigates the problem. We have a presumptive presidential nominee whose loved ones are now defending him by assuring us he’s not guilty of actual assault. Trump’s way with women is OK, they imply, because his degradation is verbal not physical.

That attitude was wrong decades ago, and even more so today.