Trump’s Nebulous “Iron Dome” Pledge Actually Reflects Very Real Homeland Threats

Former President Donald Trump, who is running for the office again, says he will build an “iron dome” defense system to shield the entire United States if he is re-elected this fall. The pledge is vague and has already prompted intense speculation about what is actually being proposed. So what is he talking about here and is any of it even relevant? You might be surprised by the answer.

First off, let’s get this out of the way, Israel’s Iron Dome system isn’t really applicable here, at least in a broad sense, as it is primarily aimed at protecting against low-end, localized threats, not broad area ones. Specifically, this includes artillery rockets with some drone and cruise missile intercept capabilities now also being featured. These threats are different than the far higher-end long-range ballistic missiles that have been the main focus of domestic ground-based air defense systems for many decades, but that’s now changing.

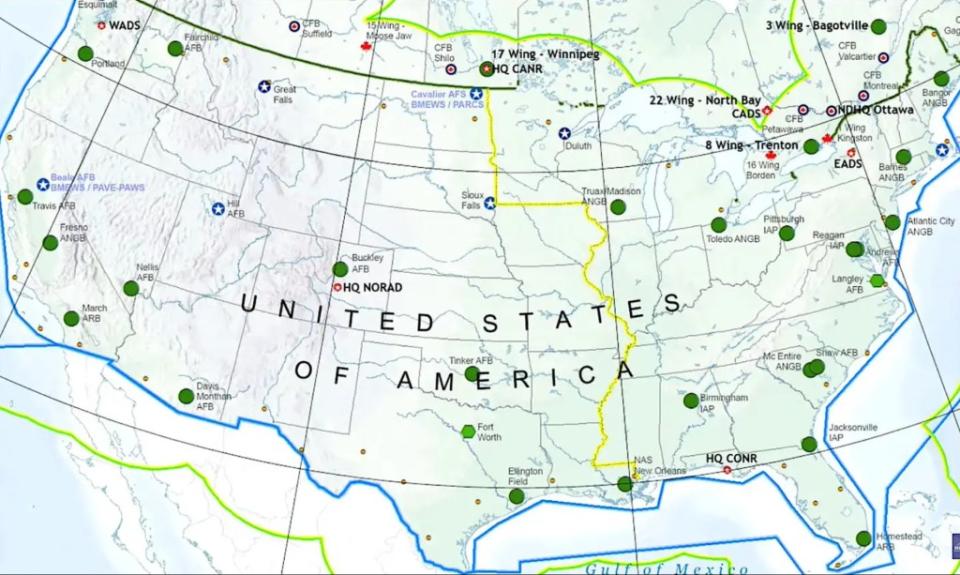

Most don’t realize that outside of the U.S. Capital Region and a few dozen ICBM interceptors in Alaska and California, the U.S. has no standing surface-to-air missile systems defending its territory or critical infrastructure. While military units could be deployed domestically in a crisis, that is easier said than done outside of the absolute most dire of crises. Target deconfliction in domestic airspace and plugging into the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command’s (NORAD) existing air defense architecture is a special capability set. These assets are also in relatively low supply and extreme demand globally, and would be especially so during an actual conflict.

Today, America’s skies are policed by U.S. Air Force fighter squadrons tasked with and trained for this specific mission set. And outside the caveats we mentioned a moment ago, they are the only assets readily able to use deadly force against targets that threaten the homeland.

Whatever the details are of what Trump is really promising, there is actual relevance to the problem he is trying to address. The U.S. military has been increasingly voicing deep concerns about the lack of air and missile defenses to help guard the homeland, especially the rapidly growing threat posed by cruise missiles and drones.

Trump highlighted the proposed air and missile defense project in an acceptance speech on July 18 following his formal nomination as the Republican Party candidate for the 2024 U.S. presidential election. “We will replenish our military and build an iron dome missile defense system to ensure that no enemy can strike our homeland,” he said in his remarks, which came on the last day of the Republic National Convention (RNC) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Trump, who was speaking at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was essentially reiterating the official Republican Party platform for the 2024 election, which includes a promise to “build a great Iron Dome Missile Defense Shield over our entire country – all made in America,” but includes no details about what this might consist of.

The former president has made this pledge in other previous campaign speeches, as well.

"In my next term, we will build a great Iron Dome over our country." — Trump pic.twitter.com/m7VsyTurAD

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) June 22, 2024

In his acceptance speech last week, Trump did make direct mention of the Israeli Iron Dome system, which typically consists of launchers loaded with fast and agile Tamir interceptors and associated air defense radars linked together via a centralized fire control system. Iron Dome was originally designed primarily for what is commonly referred to as the counter-rockets, artillery, and mortars (C-RAM) mission.

Iron Dome first entered service in Israel in 2011 and has been regularly employed since then. The systems have been very heavily utilized with thousands of Tamirs fired just in the course of the fighting that erupted following the Palestinian terrorist group Hamas’ unprecedented attacks on southern Israel on October 7, 2023.

Iron Dome’s capabilities have expanded over the years and manufacturer Rafael says the system now has a demonstrated ability to defeat cruise missiles and drones. A navalized Iron Dome system is now also in service in Israel integrated onto the country’s Sa’ar 6 class corvettes and scored its first kill in April. In Israel, Iron Dome is just one layer of an expansive integrated air and missile defense network — arguably the most advanced and densest on earth — that you can read more about here. While Iron Dome is very capable and the most combat-proven modern SAM system in service, it is not used for very broad area air defense. Covering major population centers in Israel is one thing, doing it across the entire U.S., or even just its shores, is another.

In his remarks at the RNC, Trump also drew a comparison between his “Iron Dome” and the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) that began under President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Derisively nicknamed “Star Wars” by its critics, SDI was a multi-component missile defense plan that envisioned an array of ground and space-based weapons, ranging from physical interceptors to more novel options like particle beams, along with sensors and communications networks to protect the United States from the threat of a Soviet nuclear strike.

SDI never came close to achieving its ambitious goals, but research and development work on its various components resulted in important leaps forward in various technological domains. President Bill Clinton formally ended SDI in 1993 and put U.S. military missile defense efforts on a track that eventually evolved into the current Missile Defense Agency (MDA).

Regardless, relating this initiative to SDI indicates it is a far more ambitious concept than just deploying lots of Iron Dome systems to key areas or just beefing up basic air defense capabilities domestically.

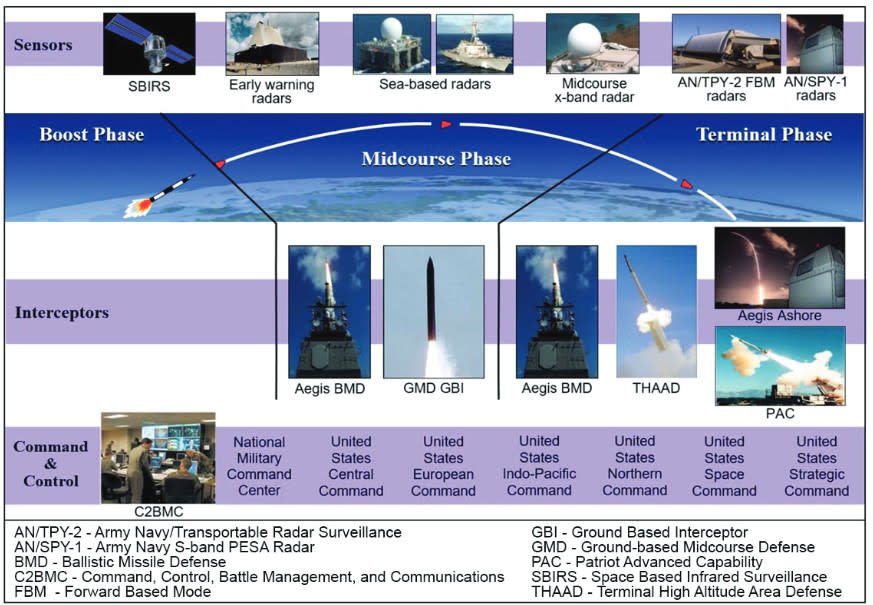

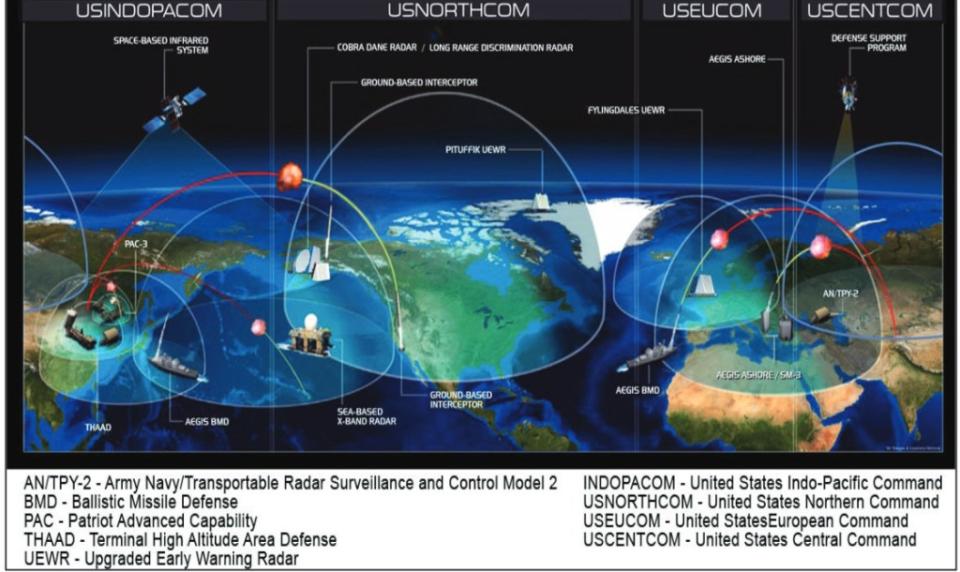

As it exists today, outside of the Capital, the missile defense architecture positioned in and around the United States is primarily geared toward defeating higher-end ballistic threats, and now increasingly novel hypersonic ones, and has limited fields of coverage. Republican members of Congress have been and continue to be especially prominent supporters of expanding those capabilities, including an ongoing push for the establishment of a ballistic missile interceptor site on the East Coast, as you can read more about here.

Outside of the Capital Region, the task of defending the United States against air-breathing and other non-ballistic aerial threats like aircraft, both crewed or uncrewed, as well as cruise missiles, and even balloons, falls almost exclusively to U.S. Air Force (to include the Air National Guard). As noted earlier, there are short-medium-range ground-based surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems positioned around Washington, D.C., and the greater National Capital Region (NCR). However, the United States hasn’t seen SAMs fielded on a broader basis across the country since the 1970s.

The U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps are working to expand their air and missile defense forces, with a major emphasis on defending against cruise missiles and drones. The Marines are even acquiring a service-specific version of Israel’s Iron Dome, elements of which will be built in the United States by Raytheon in cooperation with Rafael, called the Medium-Range Intercept Capability. The Army is working toward fielding a system called Enduring Shield that is very similar in form and function to Iron Dome, but uses the AIM-9X Sidewinder as its interceptor.

The Army had also acquired a small number of Iron Domes, but ultimately decided not to field them, in part because of issues networking them together with its other systems. The service’s Iron Domes were transferred to Israel last year to help bolster that country’s defenses.

Regardless, the Army and Marine Corps pushes to increase their air and missile capacities remain heavily focused on supporting current and future operations abroad. Both services’ plans are also geared mainly toward filling critical gaps in short and medium-range systems not meant to provide broad-area air and missile defense capabilities that would be better suited for general domestic duty.

The Army’s air defense branch is already in particularly high demand and spread thin, as The War Zone has highlighted in the past with specific respect to the service’s Patriot surface-to-air missile systems. The long-range Patriot system is designed to provide broader area defense.

At the same time, America’s near-peer competitors China and Russia continue to develop more capable air-breathing cruise missiles, including types claiming to have hypersonic performance. Those countries have also been developing new launch platforms, especially advanced ultra-quiet submarines, which could put those weapons well within range of critical military and civilian targets inside the United States. Containerized missile system could also be used transform an array of other vessels into launch platforms. The real possibility of launchers being hidden on ostensibly commercial cargo ships has been an acute point of concern for years now.

“The thing that I really want to emphasize here is that the homeland is not a sanctuary any longer,” U.S. Air Force Col. Kristopher Struve, the vice director of operations for the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), said during a virtual roundtable hosted by the Missile Defense Advocacy Association (MDAA) in 2021. “There are opportunities for our adversaries to employ weapons from distances that they could strike critical infrastructure in the United States early in a conflict and create some challenges for us to produce our military power.”

Many smaller nations, especially Iran and North Korea, have been building up their cruise, as well as ballistic missile arsenals, and those capabilities are continuing to proliferate, even among non-state actors. Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen have been waging a very serious anti-ship campaign in and around the Red Sea using anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles, kamikaze drones, and other uncrewed platforms.

The onboard camera captured the moment when a missile launched by the Houthis from Yemen struck the Malta-flagged and Greek-owned MT ZOGRAFIA bulk carrier in the Red Sea on Tuesday. pic.twitter.com/ZB60Jfu9ZG

— Status-6 (Military & Conflict News) (@Archer83Able) January 19, 2024

The Houthis are the first to have ever fired an anti-ship ballistic missile in anger. The group also has a long history of attacking targets ashore in the Middle East, most recently in Israel. The Houthi’s drone and missile attacks on Saudi oil infrastructure in 2019 were wake-up calls to these threats, as The War Zone pointed out at the time.

Drones, even lower-end weaponized commercial types, present an ever-growing threat in their own right, something that the war in Ukraine has helped finally push into the mainstream consciousness. The barrier to entry in this domain is extremely low, with terrorists, criminal groups, and other non-state actors – like the Houthis – increasingly using uncrewed aerial systems to launch attacks, as well as to conduct surveillance. Even relatively cheap examples of these systems can fly over extreme distances and strike with pinpoint accuracy. Their low and slow characteristics, and the fact that launch points can come from so far away, make them very hard to defend against. This poses a whole new threat dimension to the U.S., one in which the homeland is clearly vulnerable.

Unverified video reportedly showing a Shahed-136 strike on a building in Kharkiv on June 10. pic.twitter.com/aOGe2ktssK

— War Monitor (@WarMonitors) June 30, 2023

Looking outward for drone threats from America’s borders only factors in one facet of the issue. Attacks present the additional danger of being something that small groups or even individuals within the United States, can readily mount. The complexity of these potential attacks will only increase as the hardware and software to execute them proliferates even in the commercial space.

The War Zone has been sounding the alarm about drones of many capability types for years, including in regards to their threat to the homeland. This is only becoming more dire as uncrewed aerial systems look to be on the cusp of taking another dangerous step forward thanks to developments in autonomy supported by work on artificial intelligence and machine learning.

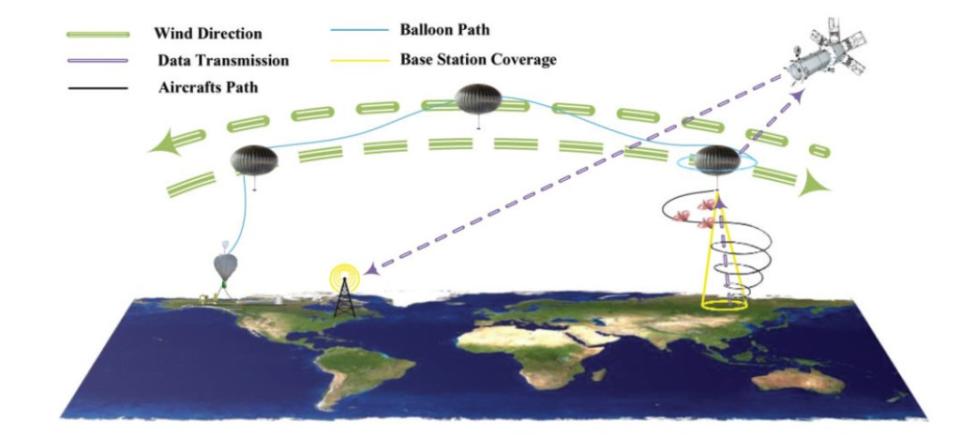

Reports of concerning drone activity over military bases and training ranges, as well as other sensitive sites, inside the United States, are only becoming more commonplace. U.S. authorities have said that many sightings of what are now commonly called unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP), previously referred to as unidentified flying objects (UFO), have been assessed to have been uncrewed aircraft, as well as balloons, on closer examination, as well. It’s worth noting here that the U.S. military and other armed forces around the world, especially China, have been actively working to develop and field high-altitude balloons as penetrating launch platforms for drones and munitions, among other missions.

Just in March, The War Zone broke the news that Langley Air Force Base in Virginia, a major East Coast air defense hub, had been swarmed by drones for several weeks in December 2023, prompting a whole-of-government response that you can read more about here.

All of this, in turn, is already driving demands for additional layers of defense from within the U.S. military, as well as both sides of the political aisle. It has also been highlighting worrisome deficiencies. The intrusion of a Chinese spy balloon into U.S. and Canadian airspace in 2022 exposed what U.S. military officials conceded were serious gaps in general situation awareness that they said immediate steps had been taken to try to mitigate. That balloon, as well as three other still unidentified objects, were subsequently shot down over and around the United States and Canada by U.S. Air Force fighters.

“I will tell you that we did not detect those threats. And that’s a Domain Awareness gap that we have to figure out, but I don’t want to go into further detail,” now-retired Air Force Gen. Glen VanHerck, then head of NORAD and U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM), said in February 2022. VanHerck was referring at that time to a series of spy balloon incursions into U.S. airspace dating back to former President Trump’s term in office.

There is a major debate ongoing now between the U.S. military and Congress about the best way forward to increase protection, especially at U.S. air bases, including domestic ones, against missiles and drones. The pros and cons of expanded use of hardened aircraft shelters and active air and missile defenses like SAMs have been particularly hot topics of discussion. New and improved weapon systems, including high-power laser and microwave directed energy weapons, sensors, and communications networks, are in the mix, too.

Specifically re-establishing a larger network of SAM sites within the United States to protect critical infrastructure and population centers has been under consideration at the highest levels of the Pentagon, as well as within NORAD, in recent years. At the same time, U.S. military officials have generally agreed that it would be unfeasible and uneconomical to provide this kind of active defense coverage across the entirety of the United States.

“We would place defenses on key critical infrastructure nodes. It’s infeasible that we can place kinetic, you know, surface-to-air missile batteries over the entirety of the United States, Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, and Canada. By the time we fielded such a system, it would probably — they would’ve found a way around it anyways,” NORAD’s Col. Struve said in 2021. “So we are working closely with OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense] and the National Security Council on where are we going to place those limited ground-based air defense assets that we’ll have in time of conflict to really change our adversaries’ calculus about their efficacy of being able to execute an attack on the U.S.”

“Simply put: We cannot defend everything,” now-retired Army Lt. Gen. A. C. Roper, then Deputy Commander of U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and the Vice Commander of NORAD’s U.S. component, said in 2022 at an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank. “Placing a Patriot or THAAD [Terminal High Altitude Area Defense] battery on every street corner is both infeasible and unaffordable.”

“Every time you start figuring out what you’re going to have to deploy to do this the way we traditionally do air defense, it is an extremely costly proposition,” another unnamed senior defense official said last year, according to Inside Defense. “So, our challenge is going to be: How do we do this smartly, right-size this thing.”

The ongoing war in Ukraine and Russia’s constant onslaught on drones, cruise missiles, with some ballistic missiles mixed in, is a reminder of just how costly things can get when you can’t protect even critical infrastructure and major population centers. At the same time, that conflict also underlines just how precious area air defense systems are and how costly they are to produce, deploy, and actually employ in a sustained manner.

Whether or not the ‘Iron Dome’ air defense shield over the United States that Trump and the rest of the Republican Party have now pledged to build materializes in any fashion remains to be seen. At the same time, there is an increasingly bipartisan consensus that threats to the U.S. homeland besides long-range ballistic missiles, and especially from cruise missiles and drones, are rapidly increasing and that new steps are required to protect Americans against them.

Contact the author: [email protected]