Trump should have picked a true conservative for the Supreme Court

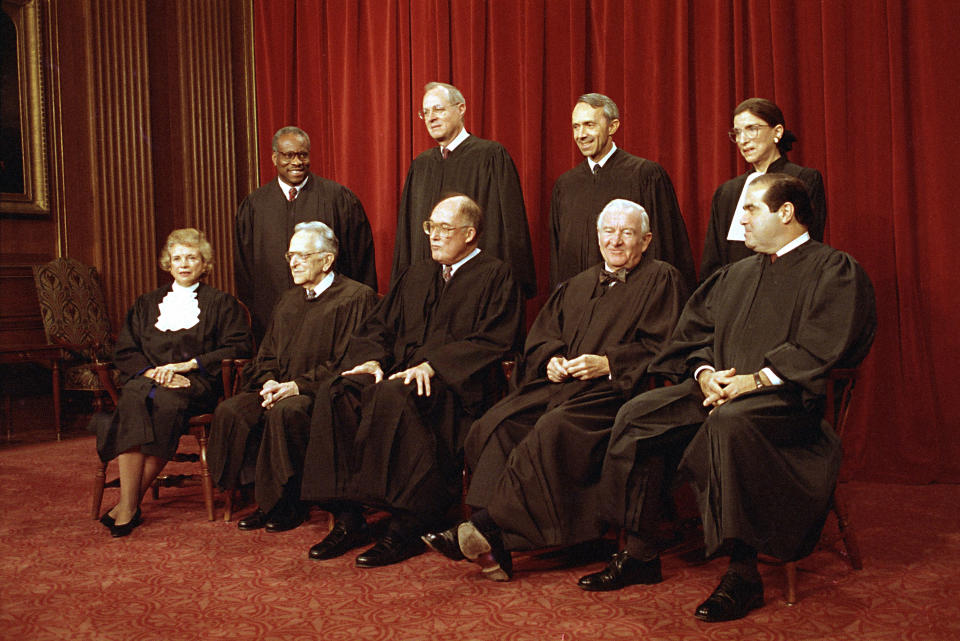

With the selection of Brett Kavanaugh, conservatives are celebrating President Trump’s move to push the Supreme Court to the right. But what, exactly, does it mean to be a conservative Supreme Court justice? The model most commonly touted is the late Antonin Scalia, who, along with Justice Clarence Thomas, held down the court’s right flank for nearly two decades before his death in 2016. A better model — a healthier example for preserving a stable constitutional democracy — would be Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who exerted far more power than Scalia over the court’s decisions during her almost 25 years (1981-2006) on the bench. Best known as the court’s first woman, O’Connor should be remembered for the wisdom of her restrained approach to the law.

Scalia liked clear, bright-lined opinions. But he rarely forged a majority; indeed, his friend Ruth Ginsburg had to privately warn him that he was alienating his Brethren. O’Connor’s opinions were far more incremental and cautious (and not nearly as fun to read). But she had an uncanny sense of finding the middle ground that not only produced court majorities but more or less helped keep the court from getting too far ahead — or too far behind — the American body politic. She was in the majority in 5 to 4 cases some 330 times. She disliked the term “swing vote” because it conveyed fickleness, but she was so often the decisive vote that, by her second decade, the press began referring to “the O’Connor Court.”

On the two most divisive issues — abortion and affirmative action — she found a way to split the difference. She discarded the unworkable trimester system of Justice Harry Blackmun’s majority opinion in Roe v. Wade to preserve a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion — while giving the states significant leeway to limit it. Similarly, she did not close the door on using racial preferences in hiring, awarding government contracts or school admissions, but she steered institutions away from explicit quotas and narrowed the circumstances when race could be a factor.

She rejected rigid formulas. O’Connor was a staunch conservative when it came to the power of the executive to wage war, but she did not believe the president’s power was absolute. In the Hamdi case in 2004, she argued that the government could not just lock the door and throw away the key on War on Terror prisoners. A state of war is “not a blank check for the president,” she wrote, with a rare turn of phrase. A firm believer in the separation of powers and the role of an independent judiciary, she emphasized that the courts have a role to protect individual liberties even in times of war.

Her critics complained, with some justification, that her avoidance of inflexible rules made it hard for lower court judges and litigants to know what the law is. O’Connor liked vague “reasonable man” standards, and her successor, Justice Samuel Alito, pointed out that the answer to the question of what is “reasonable” sometimes turns out to be whatever the judge says it is.

As a person, O’Connor could be — she would be the first to admit — directive. She told her law clerks not to chew gum and when to exercise. But as a judge she was modest, humble, a minimalist. She didn’t go around invoking great jurists as her avatars; she implicitly followed the model of Judge Learned Hand, who said that the spirit of liberty is the spirit which is “not too sure it’s right.” She was keenly sensitive to unintended consequences, that hard cases can make bad law. Most important, she understood that the highest court in the land was not some Olympian last word, but rather a critical participant in an ongoing national debate over right and wrong. She was perfectly content to send questions back to the lower courts or political institutions to let the debate go on, to allow consensus to emerge slowly.

Once, famously, she decided that time had run out. In Bush v. Gore, she voted with the majority to stop the Florida recount, effectively guaranteeing George W. Bush victory over Al Gore. O’Connor was not one for looking back and second-guessing. A tough cowgirl raised on a ranch, she understood the need to step in and fix the problem. But in this one instance, she did wonder if perhaps the court might not have found a way to duck the case.

Almost all modern Supreme Court justices have come from elite Ivy League schools (usually Harvard) and sat on federal Courts of Appeal. The Arizonan O’Connor went to Stanford (before it became a powerhouse) and was the only justice to have run for office. The first woman ever elected majority leader of a state senate, she had a natural feel for politics and for the importance of politics.

It is possible that Kavanaugh will turn out to be like O’Connor, a pragmatist in the pursuit of principle. But in the years ahead, the justice to watch will probably not be Trump’s latest appointee, but rather the chief justice. John Roberts is somewhat more ideological than O’Connor, but he shares— at least to some degree — her sense of the practical. He is likely to be the decisive vote on hard cases like abortion and affirmative action. Let’s hope he takes the path not of Antonin Scalia but of Sandra Day O’Connor.

Evan Thomas, a journalist and historian, is working on a biography of Sandra Day O’Connor.

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court: