In Trump Supreme Court immunity appeal, timing of case could be a win for ex-president

In the wake of the Supreme Court's decision to hear former President Donald Trump's presidential immunity appeal in late April, legal experts disagree on whether the scheduling is a gift for the Republican frontrunner — and whether it signals the justices may be sympathetic to his argument or desired timeline.

Scheduling oral arguments for two months after that decision is faster than the court's typical timeline for hearing cases. It leaves open the the possibility of a trial in Trump's federal election interference case before the election.

Still, liberal critics ? who noted the court has moved more quickly in urgent cases ? lambasted the schedule for potentially delaying a trial or verdict until after the November election. Many fear Trump will take the unprecedented step of ordering the Justice Department to drop the criminal case if he becomes president next year.

"They've created a schedule that I think is going to make things very, very difficult, and so I think the idea that the Supreme Court is going to be some form of salvation here is not a sound one, we don't have any reason to believe that," said Sherrilyn Ifill, the former head of the the NAACP legal defense fund, on MSNBC.

A trial falling further behind schedule

Trump's Washington, D.C. federal election interference case, from which the Supreme Court appeal arose, is on hold. He faces charges of conspiring to defraud the country and obstruct the presidential election certification process in order to overturn his 2020 defeat.

District Judge Tanya Chutkan initially scheduled the trial to start March 4, but agreed with Trump that many pre-trial proceedings needed to be paused as he appealed over the presidential immunity issue.

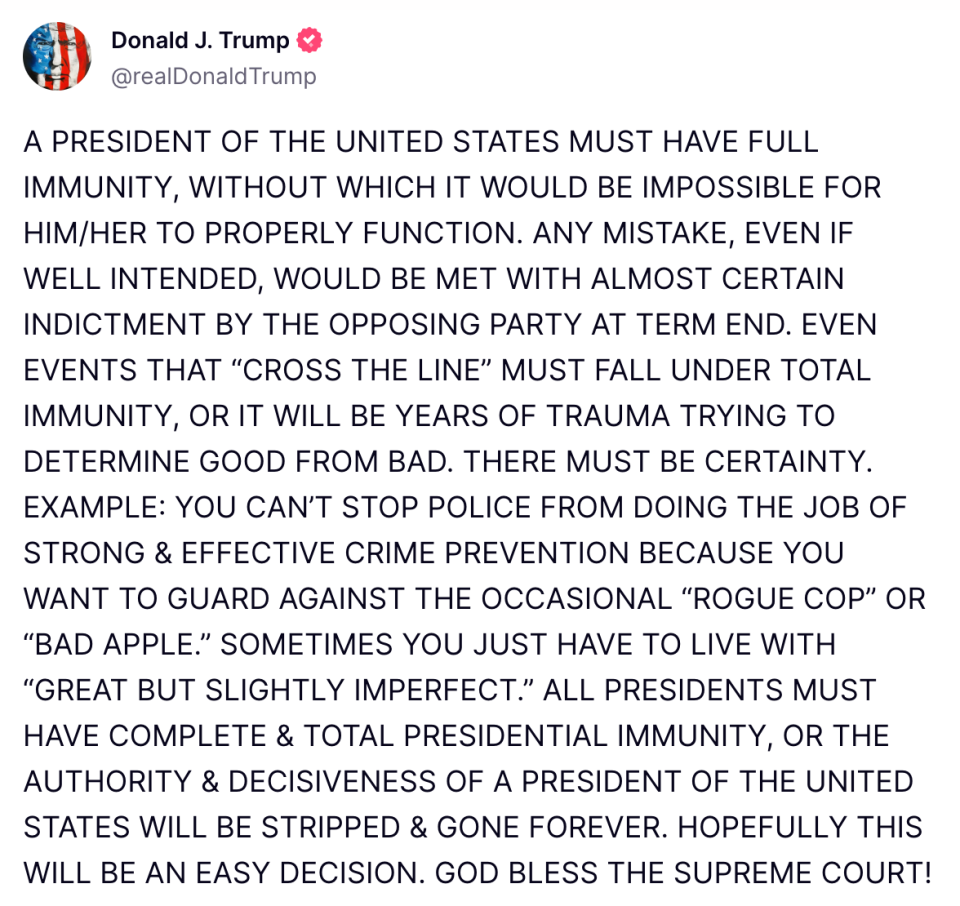

Trump's legal team has argued that the targeted actions in the indictment fell within the scope of his presidential duties, and he therefore "is absolutely immune from prosecution." That stance was rejected by Chutkan and later unanimously by a federal appeals court three-judge panel.

Special prosecutor Jack Smith has argued that legal principles and historical evidence show former presidents are subject to federal criminal prosecution "like other citizens," and even if there were permanent criminal immunity for presidential actions, the case would survive because that immunity wouldn't encompass every allegation in the indictment.

Chutkan tossed out the March 4 date as the immunity appeal dragged on.

Did the Supreme Court speed up or slow down?

Anticipating exactly this potential time crunch, Smith asked the Supreme Court to leapfrog an appeals court and take the case on Dec. 12, 2023. The justices declined. After Trump lost at the appeals court and asked the high court to keep the case on hold on Feb. 12 pending his expected appeal to the Supreme Court, the justices could have refused his request, and ultimately let the appeals court ruling stand.

As several days went by without the high court taking the case and scheduling arguments, some observers thought the justices might be preparing to do just that, especially since Trump had argued for extremely expansive immunity. A president who ordered a political opponent's assassination could not be prosecuted, Trump's lawyer told the appeals court, unless he is first impeached and removed from office. The appeals court had already issued a lengthy ruling denouncing his claim "that a President has unbounded authority to commit crimes that would neutralize the most fundamental check on executive power — the recognition and implementation of election results."

Instead, the justices waited two weeks, granted Trump's request, decided to review the case, and then set a schedule that pushed oral arguments out about two more months, to the week of Monday, April 22 (the court has since settled on Thursday, April 25 as the exact date). It takes four justices to decide to hear a case and typically five to place or keep proceedings at a lower court on hold.

If the justices wanted to weigh in, why didn't they just take the case back when Smith asked them to? The most plausible explanation, some say, is to help Trump, and that implies they will be on his side through the rest of the case.

When the justices take about two weeks "to issue this order, and then they come back and they say we're going to get to these arguments in seven weeks, they are going up to that calendar and they are putting nine weeks of days and they are burning them for Donald Trump," MSNBC host Chris Hayes said on "The Late Show With Stephen Colbert."

"If they wanna move fast after April 22 and they want to issue that opinion, they can. Do I think they will after what they signaled today? Not likely," Hayes said.

The Supreme Court is capable of moving faster than it has chosen to thus far in the case. In Bush v. Gore, the case that suspended a Florida recount and effectively declared George W. Bush the 2000 presidential winner, the court accepted, heard, and decided the case in under a week. In Trump v. Anderson, in which the justices kept Trump on the Colorado ballot Monday, they accepted the case in two days, scheduled arguments for less than five weeks later, and issued an opinion within a month from there, in advance of the Super Tuesday presidential primaries.

Still, under normal procedures the justices could have waited much longer simply to schedule arguments, and then held those arguments in the fall.

"The briefs are due very soon, the orals are in April, that's actually a pretty expedited review at this point," said David Schultz, a visiting law professor at the University of Minnesota who teaches about election and constitutional law.

"I know some people are saying, 'Oh, the court's delaying on this.' No, I think they're actually moving pretty quickly on this one," Schultz told USA TODAY.

Some — though probably not all — of their two-week delay in deciding whether to take the case and how to schedule it could be explained by the unusual procedural issues they were faced with, according to Leah Litman, a University of Michigan law professor and former clerk to retired Justice Anthony Kennedy. She noted on Strict Scrutiny, a legal podcast that issued two March 4 episodes discussing the case, that Trump had only asked the justices to keep the case on hold, but Smith asked them to treat Trump's request as a request for Supreme Court review.

Nonetheless, Litman thought the court took longer than it needed.

"There are some things to sort out — I don't think two weeks of things to sort out," Litman said on the podcast.

Andy Grewal, a law professor at the University of Iowa, argued that the high court's schedule is "lightning fast" for a question that involves not just Trump, but the entire institution of the presidency. The normal procedure for this type of question, he said, would be to schedule arguments for October and then sit on the case for months while trading drafts before issuing a decision.

"If it wasn't for this election, there's no way the Supreme Court would rush such a monumental decision," Grewal said.

Impartial justice?

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas' wife, conservative activist Ginni Thomas, advocated in messages to state lawmakers and Trump's chief of staff for efforts to overturn Biden's election, which she called the "greatest Heist of our History." She also attended Trump's Jan. 6 "Stop the Steal" rally that preceded the attack by other Trump supporters on the Capitol.

Nonpartisan good-government advocates including Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington have called on Thomas to recuse himself from Jan. 6-related cases. Thomas has largely ignored those requests, although he recused himself from one Jan. 6-related case involving his former law clerk, John Eastman.

Looking out for their legacy

Two of the six Republican-appointed justices on the court — Thomas and Samuel Alito — are in their seventies. Perhaps those justices, nearing the question of who will replace them, would like to see Trump win, and therefore don't want a trial that could hurt Trump's chances before Election Day, Melissa Murray, a New York University law professor, said on Strict Scrutiny.

"There are two septuagenarian justices who might want to step down under a Republican president and have their replacements be movement conservatives just like them," according to Murray.

"For that reason, maybe they're just not that inclined to throw a wrench in the works that subjects their preferred candidate to a criminal trial where he might be found guilty and be wearing an orange jump suit on January 20th," Murray said.

What a ruling could look like

Michael McConnell, a Stanford law professor and former federal judge, pointed to the Supreme Court's framing of the issue it will address as a signal of how it may rule. In its Feb. 28 order agreeing to hear the case, the court said it will review whether "and if so to what extent does a former President enjoy presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts during his tenure in office."

The court's language departed significantly from proposals both Smith and Trump made in December for what the justices should address. They asked the court to weigh in on "absolute immunity" for a former president or for a president's official acts, as well as on how congressional impeachment proceedings could impact potential presidential immunity.

The Supreme Court, by contrast, didn't explicitly raise the idea of "absolute immunity" at all, and its "if so to what extent" phrasing might indicate an interest in applying immunity to some actions but not others.

"It is significant that the Court revised the question presented to avoid the all-or-nothing questions both sides prefer to raise," McConnell told USA TODAY.

McConnell said the court will likely conclude former presidents have immunity for some acts within their official duties, but not for others — such as acts committed in their capacity as reelection candidates.

Jack Goldsmith, a Harvard law professor and former clerk to retired Justice Anthony Kennedy, suggested on X that the justices may be considering presidential immunity for a subset of official acts — such as acts within the executive branch's most core functions.

"Such a ruling might, however, leave the district court w/ legal work to do, on remand, before trial—not sure," Goldsmith posted.

Grewal highlighted portions of the indictment that target Trump's handling of the Justice Department as an area where the Supreme Court — or a lower court tasked with implementing its ruling — might take issue. Smith alleged that Trump tried to use the Justice Department to open sham election investigations and influence state legislatures with claims of fraud that Trump knew were false.

"When it comes to managing the DOJ, that's something only the President does," Grewal said.

Grewal added that he "can't imagine that all the counts of the indictment would be dismissed, because it describes some things that just really don't sound like Trump was acting like the President at all."

Smith accused Trump in the indictment of pushing state officials to disenfranchise voters, trying to enlist then-Vice President Mike Pence to fraudulently alter the election results, and repeating election fraud claims he knew were false to supporters while directing them to the Capitol to obstruct the election certification process.

Trial back on track or even more delay?

Schultz said the high court could issue a ruling that calls for distinguishing between allegations that are and are not protected by presidential immunity, but then leave it for a jury to apply that distinction at trial.

But the court could also order trial Judge Tanya Chutkan to make that determination, thereby creating another round of pre-trial proceedings.

"If that's the case, with another round of briefing and decisions in the lower courts, then any prospect of a trial before the election is decisively eliminated," University of Pennsylvania law professor Kate Shaw said on Strict Scrutiny.

"It will take time to scour through the indictment to separate the wheat from the chaff, which will make it difficult for the trial to take place before the election," McConnell said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Does Supreme Court schedule on Trump immunity signal how it will rule?