What is the confirmation process for Cabinet picks — and what are ‘recess appointments’?

President-elect Donald Trump continues to push his friends and closest allies as nominees for key roles in government. The picks have sent shockwaves through the hall of Congress.

Trump has vowed to get them into their positions — and it's been floated that he could do something that hasn’t been done in the nearly 250-year history of America to make it happen. How would he achieve this, when usually he would have to go through an official confirmation process? Through recess appointments.

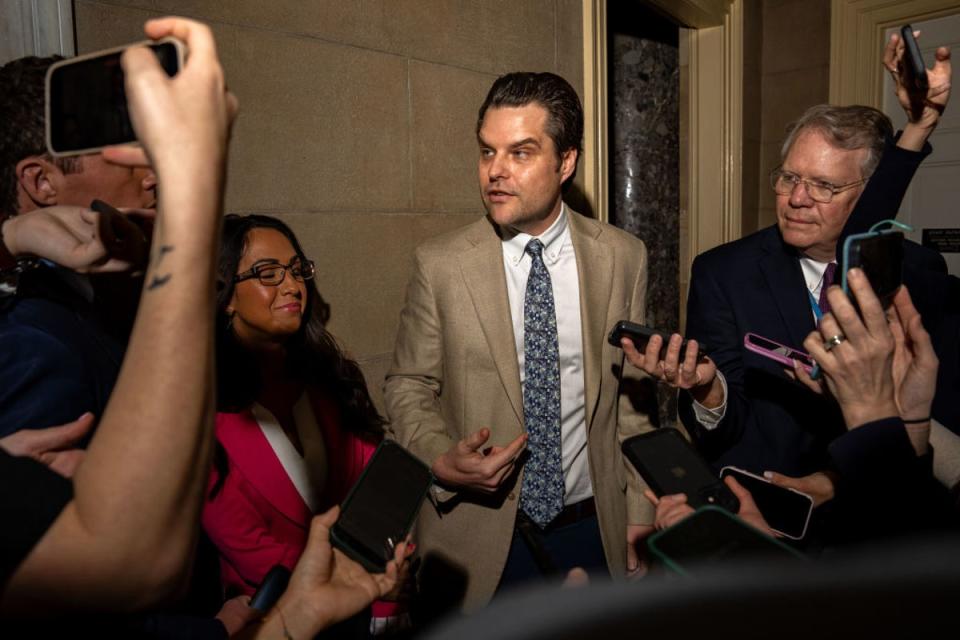

Some of Trump’s most controversial choices so far include Robert F Kennedy Jr, the environmental activist-turned-vaccine-conspiracy theorist, for secretary of Health and Human Services; former congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard to be Director of National Intelligence; and former congressman Matt Gaetz to serve as attorney general.

Republican Senators seemed downright uncomfortable talking about the picks when asked. Democrats don’t seem too enthused about helping Trump if any Republicans defect.

“I've got a lot of questions, and that’s why we have advise-and-consent,” Senator Mark Warner, the top Democrat on the Intelligence Committee, told The Independent. “And the first step is to go through appropriate background checks. Then there’s a public hearing and then I'll reach a conclusion.”

Warner was being polite compared to Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who sits on the Armed Services Committee, which would be in charge of confirmation hearings for Fox News pundit Pete Hegseth, Trump’s nominee to lead the Pentagon.

“Being on Fox News is not enough to substitute for the kind of experience that years in different parts of the military and grappling with different issues in defense give to a possible nomination,” she told The Independent.

Trump will come to Washington with a sizeable Republican majority in the Senate after Republicans flipped seats in Montana, West Virginia and Ohio. Pennsylvania’s Senate race is currently in a recount, but if incumbent Democratic Senator Bob Casey loses, that will give Republicans one more vote to confirm Trump’s team in the form of Dave McCormick.

At the same time, it might not be enough. Even in an era where Republicans are far more subservient to Trump than his first go-around in office, some Republicans will not want to bend the knee and vote for unqualified nominees.

Enter recess appointments. Earlier this week, as Republicans geared up to nominate their new majority leader, Trump tweeted: “Any Republican Senator seeking the coveted LEADERSHIP position in the United States Senate must agree to Recess Appointments (in the Senate!)”

Article II of the US Constitution states that: “The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.”

Essentially, recess apppointments are when the president appoints a nominee to a Senate-confirmed position when the Senate is out of session, bypassing the need for colleagues’ say-so. Historically, Democrats and Republicans have used recess appointments for controversial nominations. Bill Clinton made 139 recess appointments, including one for James Hormel as US ambassador to Luxembourg, after Republicans opposed Hormel’s nomination because he was openly gay.

Recess appointments expire at the end of the Senate’s next session, according to the Congressional Research Service.

But since 2006, when Democrats took control of the House and Senate during George W Bush’s administration, the Senate has essentially stopped having recess appointments. Rather, it holds what are called “pro forma” sessions, wherein the House and Senate briefly conduct business as a way to prevent presidents from making recess appointments.

In 2012, as Senate Republicans continued to block Barack Obama’s nominees to the National Labor Relations Board, he made three recess appointments. However, in 2014, the Supreme Court ruled against Obama doing so, saying the Senate hadn’t been on a long enough recess to justify making appointments during that period.

That leads us to the next part, which would be unprecedented. Section 3 of Article 3 in the Constitution says that the president “may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper.”

That rule would allow Trump to adjourn Congress as long as he likes — allowing him the leeway to make a legally justifiable recess appointment.

This is not the first time that the president-elect has hinted at the need to do this. In 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Trump signaled that he would be interested in doing so. But even some Senate Republicans might chafe at the idea of the president using this power.

“It’s in the Constitution, but again, our job is to provide advice and consent,” Senator John Cornyn of Texas told The Independent on Thursday. “I think that’s sort of a failsafe in the event Democrats continue to block any of President Trump’s nominees. He has a right to get his team in place without unnecessary delays.”

Ironically, during that last time Trump threatened to adjourn Congress, he did so when Republicans — led by then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell — controlled the Senate. The divide between Trump and McConnell showed just how protective the Senate is about its “advise-and-consent” power that is enumerated in the Constitution.

The next Senate majority will not be led by McConnell, who announced at the beginning of this year that he would step aside as Republican leader. Rather, Senator John Thune, who currently serves as minority whip, will be the majority leader in January.

Thune beat Cornyn, a decidedly more conservative Republican, during the race to become majority leader earlier this week. But if Trump continues to push and prod Republicans on this, it could likely lead to Trump at least trying to adjourn Congress as a flex of his power. A flex that hasn’t been seen in three centuries.