Trump’s New York criminal trial begins soon – but will the public care?

As the criminal cases mounted against Donald Trump last year, one could be forgiven for not giving much thought to the New York case that charged him with 34 felony counts for falsifying business records.

Related: Ex-Trump Organization CFO Allen Weisselberg sentenced to five months for perjury

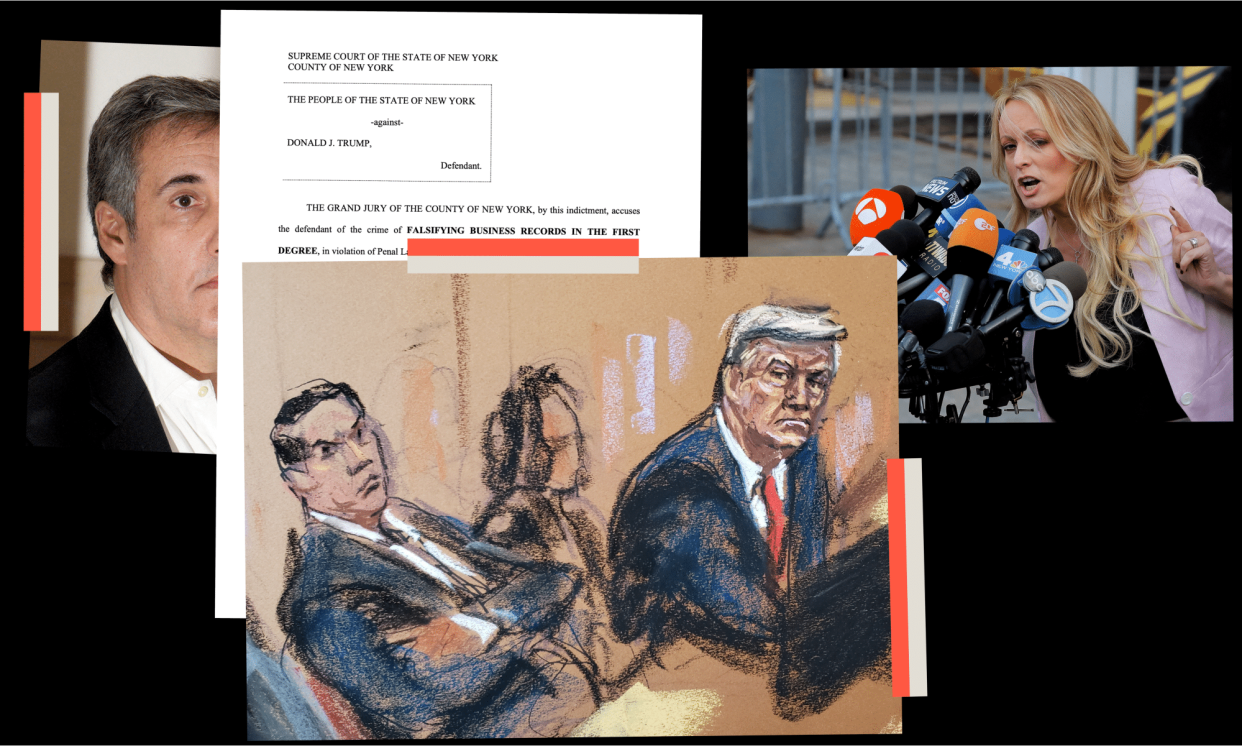

The episode was a bombshell when the Wall Street Journal first reported it in January 2018. Trump paid the adult film star Stormy Daniels $130,000 on the eve of the 2016 election to keep quiet about an affair. He funneled the payment through his lawyer, Michael Cohen, and then lied about the purpose of the payment in his business records. By the time the case was filed last year, it had largely faded in the public psyche – buried under Trump’s efforts to steal the 2020 election and an avalanche of other lies.

Now, the once-sleepy case will be the first time a former president has gone to trial on criminal charges. It’s an awkward incongruity – the case with what appear the more benign crimes is taking on an outsize importance by going first – and a dynamic that’s been shaped entirely by Trump, who has used an array of legal maneuvers to delay the other three criminal cases against him.

Like all of the trials against Trump, there will also be a case in the courtroom and in the court of public opinion. And first-term district attorney Alvin Bragg will need to clear both hurdles by not only presenting a cut-and-dried case about falsifying business records, but reminding the American public who the true victims are: themselves.

“The prosecutor is going to want to sort of detail a precise case of ‘these are the documents, it was falsified, he knew and he had the intent’ and is going to try, in some ways, to simplify and streamline this case for the jury,” said Cheryl Bader, a professor at Fordham law school who specializes in criminal justice. “On the other hand, they also want to show why this matters as a matter of election democracy and choosing the highest officer in the land.”

Bragg has already started trying to frame the case as a matter of election interference, casting the hush-money payments and efforts to hide them as part of a scheme to conceal information from voters ahead of the 2016 election.

When Bragg first filed the charges, the biggest issue in the case was whether the crimes amounted to a felony. In New York, falsification of business records is a misdemeanor, but can be charged as a felony when it is done with the intent to commit another crime. Bragg has said Trump falsified the business records with the intent to violate federal and New York state election laws, among other things – a novel way of charging the crime.

Many experts were initially somewhat skeptical of this strategy. While Judge Juan Merchan and a federal judge have both allowed Bragg to proceed to trial on this theory, it will probably be a central issue at the trial. Bragg will need to convince the jurors beyond a reasonable doubt not only that Trump falsified business records but also that he intended to violate another law.

Other Republicans and critics of the case also see the trial as a ripe opportunity to paint Bragg, a Democrat, as a partisan player. The perception that the crimes in the case are relatively minor compared with the other charges Trump faces only augments that narrative.

“If I were designing a case that would be easy for Republicans to dismiss as a partisan witch-hunt, I would design exactly this case,” said Whit Ayres, a longtime Republican pollster. “This does not look like a prosecutor fairly and objectively trying to uphold the rule of law. It sounds like a Democrat out to get Donald Trump by any possible means.”

But Karen Friedman Agnifilo, a former prosecutor in the Manhattan district attorney’s office, said the facts of the case were relatively routine, and described it as a “boring paper case” dealing with charges that are routinely brought.

New York court data obtained by the Guardian shows there have been nearly 600 cases since 2013 in Manhattan involving a charge of falsification of business records. A New York Times analysis found only two other felony cases over the last decade in which someone was charged with falsification of business records but no other crime.

“The only thing special about this case is the defendant. That’s it,” Agnifilo said. “This is not anyone bending over backwards. This is not anyone doing anything other than enforcing the law.”

Bragg had also offered to let the federal cases go first last year, noted Bader, the Fordham professor. “There’s other dockets here, broader justice may warrant another case going first, but we stand at the ready,” Bragg said in a January interview on NY1.

“There’s a little bit of an unfair comparison to say that this case isn’t as significant as the January 6 case,” Bader said. “Comparing this crime to other crimes is not a legal defense. It is like going to trial to defend against pickpocketing charges and saying ‘since it’s only pickpocketing and not armed robbery, you shouldn’t convict my client.’”

The case puts lying, a critical part of Trump’s political rise, back into the center of public discourse. It also showcases an embarrassing moment for Trump in the public spotlight – reminding voters that he was concerned enough about news of an affair getting out that he was willing to pay a substantial sum to keep it quiet.

“Hush money for sex is never really dry,” said John Coffee Jr, a professor at Columbia University.

Ayres said he was doubtful those allegations would make a difference.

“Gee, Trump screws around on his wives. Whoa, what a revelation. And then he tries to cover it up. Whoa, what a revelation,” he said. “Evangelical voters long ago made peace with the fact that Donald Trump is not exactly a model for fidelity in marriage.”

Other risks for Bragg lie ahead. A star witness in the case is Michael Cohen, Trump’s one-time confidant who has pleaded guilty to campaign finance and tax evasion charges and since been disbarred. Trump’s attorneys are likely to go hard and try to undermine his credibility when he takes the stand, making it more difficult for Bragg to convince jurors he can be believed.

“Prosecutors are used to trying cases where their witnesses are flawed and have a lot of baggage,” Bader said. “They know how to prepare a witness who has lied in the past and has committed crimes in the past to answer questions in cross-examination and to admit, right, to come clean to the jury and therefore show that they are willing to answer honestly even about the wrongs that they’ve done.”

Cohen’s credibility may also be enhanced because he is not testifying in exchange for any leniency since he has already served a prison sentence, Bader noted. “They could still say, OK, you know, he has an axe to grind and he hates Trump. But that’s a different kind of motive,” she said. “Lying on the stand because you hate somebody is different than lying on the stand because you want to save yourself from going to jail.”

But Cohen hasn’t done himself any favors. Last month, a federal judge suggested Cohen may have committed perjury when he testified in October that he hadn’t actually committed tax evasion even though he pleaded guilty to it in 2018.

It will also be difficult for Bragg to define a clear victim in the case. Stormy Daniels received a payout for her silence and Cohen also willingly accepted money. That puts the pressure on Bragg to explain why the true victims are the voting public.

“You don’t need Michael Cohen or Stormy Daniels or any victim, you know – all New Yorkers are victims because … all of us who have businesses who do things the right way,” Agnifilo said. “ If I were them, I would say this case has nothing to do with Michael Cohen. It’s more about concealing something from voters.”

Fred Wertheimer, the founder and president of Democracy 21, who has been supportive of the prosecution, said that keeping the focus on the political significance of the hush-money payments would be key.

“This is not just a hush-money case, as it tends to be described,” he said.

“The money was given to influence the 2016 election. In other words, the silence was purchased so [Daniels] would not provide damaging information in the closing weeks of his campaign.”