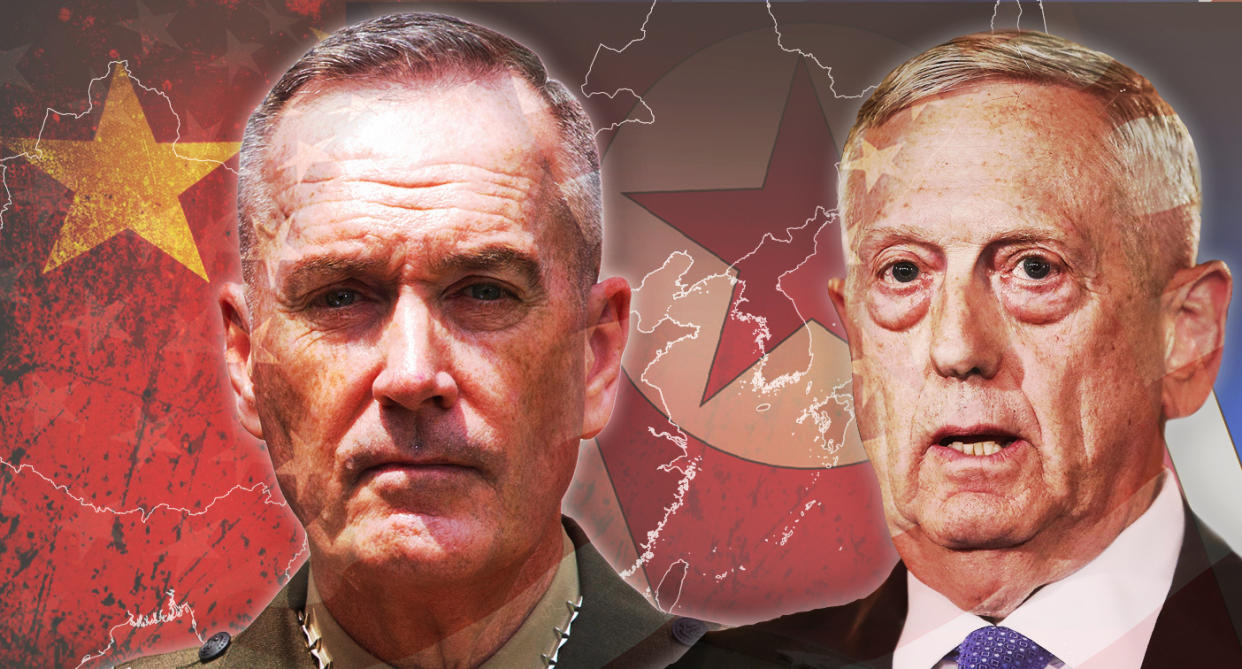

Trump’s generals try to reassure Asian allies

Singapore — The Istana presidential palace sits on a lush green hill surrounded by the towering skyscrapers of this wealthy city-state, its gleaming white columns and porticos recalling the colonial-era British Raj that built it on a former nutmeg plantation in 1867. Begun as a trading post of the British East India Company and occupied by the Japanese during World War II, Singapore today boasts one of the highest per-capita GDPs in the world and is a hub of global finance and commerce. Just off shore in the Strait of Malacca a mighty armada of cargo ships stretches to the horizon, a visible sign of the trade that has made modern Asia the most powerful economic engine in history.

On a recent morning Gen. Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was greeted at Istana by a full military honor guard and band. Singapore’s president, prime minister and military leaders ushered Dunford into a ceremony where the general was given the country’s Distinguished Service Order, a medal as big as a fist that hung from a wide ribbon draped over his shoulders. As a combat leader and no-nonsense Marine, “Fighting Joe” Dunford does not revel in pomp or personal aggrandizement. Yet he fully understood that the award was bestowed not so much to him personally, but rather for what he represents.

Like the other Asian Tigers, tiny Singapore has thrived in the rules-based international order that the United States constructed out of the wreckage of World War II. As the chief of the U.S. armed forces, Gen. Dunford personifies the enforcement of those international rules and norms, protecting allies from threats like a rogue North Korea and the encroaching shadow of a rising China asserting control over the vital shipping lanes of the South China Sea. Along with Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis, Dunford was in Singapore for the Shangri-La Dialogue, a major gathering of defense officials and foreign policy experts from across Asia. Both generals tried to assure nervous allies that the United States remains committed to an international order predicated on free trade and freedom from intimidation.

“I know there’s been noise about the United States supposedly walking away from our rebalance to Asia. That narrative is real and it’s out there in the media,” Dunford said in an interview with Yahoo News. “But when you look at the facts, we have a pretty compelling story to tell.”

Those facts include the Defense Department devoting 60 percent of its joint forces to U.S. Pacific Command, and a significant increase in the volume of multilateral military exercises in Asia. The Pentagon has also deployed the newest and most capable weapons in the U.S. arsenal to the Pacific, to include F-35 and F-22 fighter aircraft and littoral combat ships.

“We’re matching our actions to the message that the United States remains committed to the Asia-Pacific,” Dunford said. “And when you go country by country, and look at our military-to-military engagements with nations like Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Thailand, Japan, South Korea and Australia, I will tell you that the state of those relationships is very healthy, and they are absolutely valued in the region.”

Yet if facts are stubborn things, so too are narratives, especially when reinforced by the leader of the free world. As candidate and president, Donald Trump has suggested the possibility of withdrawing the United States’ protective nuclear umbrella over Japan and South Korea as retaliation for their failure to spend adequately for their own defense. He wrongly chastised Seoul for supposedly stiffing the United States for the cost of deploying the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system during the North Korea missile crisis.

Many Asian countries still feel bruised by Trump’s rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, on which Asian officials spent years and considerable political capital negotiating. They continue to argue that the web of trade relationships between the United States and its Asian allies is the underpinning of their military alliances, and critical for keeping China in check. Trump’s haranguing of NATO allies for not meeting defense spending goals, while failing to reaffirm the U.S. treaty commitment to defend its closest allies, was not lost on Asian observers. Most recently, the Trump administration’s decision to pull out of the Paris Agreement on climate change rankled Asian signatories whose coastlines are threatened by rising sea levels.

So the positive messages of U.S. commitment carried by Mattis and Dunford were greeted with relief at Shangri-La, but also with considerable skepticism. After all, the generals came as emissaries of the one man many allies fear could bring the international order in Asia crashing down.

Kori Schake, a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, and a former National Security Council staff member for George W. Bush, attended the Shangri-la Dialogue. “My sense is that in Asia, just as in Europe, Secretary Mattis and Chairman Dunford are there chiefly to reassure allies who yearn for an America that still supports the U.S.-led global order,” she said. Schake was struck by the traditional American foreign policy speech Secretary Mattis gave in Singapore, for instance, emphasizing enduring U.S. security commitments and the importance of trade in cementing relationships among countries that share common values. “I was also struck by the fact that every question Mattis fielded afterwards from the audience was a variation of ‘How can we believe you given the positions and statements of President Trump?’”

By a historic twist of fate, the first major crisis likely to test Trump’s unorthodox “America First” foreign policy is one that has bedeviled U.S. administrations for a quarter century: North Korea’s determined effort to acquire nuclear weapons and long-range missiles that can threaten U.S. forces and allies in Asia, and within an estimated two to four years the U.S. homeland as well. Responding to a rash of recent missile tests by Pyongyang, Trump administration officials have declared that the “era of strategic patience is over,” and the president has drawn a red line by insisting that North Korea will not be allowed to acquire an intercontinental ballistic missile. The tough rhetoric was recently backed by the deployment of the THAAD antimissile defense system to South Korea and a U.S. carrier battle group to the region. The stability of Asia and the very real potential for a second Korean War are now riding on Trump’s uncertain crisis management instincts, and the actions of a mercurial and bellicose Kim Jong Un in North Korea.

Given Pyongyang’s past unprovoked attacks on South Korea, its threats to attack the United States with a nuclear first strike, and its near-perfect record as a serial proliferator of its nuclear and missile technology, Mattis in his Shangri-La speech called North Korea’s nuclear program a “clear and present danger” and “the most urgent and dangerous threat to peace and security in the Asia-Pacific.” Privately, both he and Dunford walked allies in Asia through their plans to methodically squeeze Pyongyang with an ever-tighter noose of U.N. resolutions, economic sanctions and military containment. Notably, their strategy is based on the assumption that China will finally prove willing to implement potentially crippling sanctions on Pyongyang, and that North Korea can be pressured to relinquish a nuclear weapons program that it views as a guarantor of regime survival.

“I think the new United Nations resolution passed [on June 3rd] is significant, because it shows that there is now a shared sense of urgency in the international community,” said Dunford, referring to new sanctions slapped on Pyongyang after its ninth ballistic missile test this year alone. “I also think North Korea’s provocative behavior has captured China’s attention in particular. If you look at the timing of Kim Jong Un’s provocations, some of them seemed intended to insult China. [Secretary of State Rex] Tillerson has also made clear that the United States is not seeking ‘regime change’ in North Korea, but simply a denuclearized Korean Peninsula, which is a goal that China shares. So I believe the two U.N. resolutions this year and China’s concerns about North Korean behavior have set the right conditions. The entire international community is approaching this issue differently than in the past.”

Given Trump’s inexperience and past controversial statements about alliance commitments, however, a number of Asian allies are nervous about a strategy that is edging him closer to a self-declared red line, and the possibility of a preemptive U.S. strike that could have existential consequences for South Korea in particular. “I think now is the time to abstain from tough talk that might send the wrong signal or be misinterpreted in way that has unintended consequences,” said a senior South Korean official who asked not to be identified. “What we’re hearing privately from Mattis and other U.S. officials is that while ‘every option is on the table’ with North Korea, whatever the United States does will be in close consultation with South Korea.”

Mark Fitzpatrick is an Asia expert for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, which hosted the Shangri-La Dialogue. “Some of the Trump administration’s strong rhetoric may have had a deterrent effect because North Korea has not tested another nuclear device recently, but Trump’s volatile statements and controversial pronouncements about alliance commitments has understandably made Asian allies anxious,” he said. Given President Trump’s transactional approach to international relations, he noted, there’s concern among Asian allies that he might make a deal with China that trades more lax U.S. enforcement of “freedom of navigation” in the South China Sea in exchange for Beijing’s help with North Korea. “And while everyone appreciated Mattis’ assurance that the United States wouldn’t use its allies as ‘bargaining chips’ in that way, no one knows if they can really take that commitment to the bank. Only Donald Trump is the commander in chief.”

Indeed, after his meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Mar-a-Lago earlier this year, Trump revealed his transactional approach to foreign relations by backing off his oft-stated promise to label China a currency manipulator. “Why would I call China a currency manipulator when they are working with us on the North Korean problem?” Trump tweeted on April 16. “We will see what happens!”

Such transactional flexibility alarmed Asian allies who depend on the United States to be steadfast in pushing back against Chinese bullying in the South and East Asian Seas. Examples of China’s muscle-flexing are many, including dredging up seven artificial islands from reefs in the South China Sea, and claiming exclusive territorial zones around them. Beijing also ignored a binding 2016 finding by the United Nations Permanent Court of Arbitration that favored the Philippines over China in an island dispute. Chinese warships and military aircraft routinely violate Japan’s territory, and harass U.S. forces as they conduct “freedom of navigation” patrols in international waters and airspace.

“We made clear to our allies our continued support for a rules-based international order that requires the United States to uphold the principle of ‘freedom of navigation’ by operating wherever international law allows,” said Dunford, who reiterated the U.S. commitment not to use such operations in support of allied shipping as “bargaining chips” in negotiations with the Chinese. He also noted that China reversed a public pledge to the Obama administration not to place weapons systems and “militarize” the seven islands it has dredged from reefs in the South China Sea.

“It’s indisputable that China has militarized those artificial islands after promising not to do so in 2015, which tells me that they are trying to push the U.S. military further out to sea in order to prevent us from having free access to the region to meet our military commitments to allies,” said Dunford, who called China’s actions a “classic anti-access, area denial” strategy. “If you combine that with China’s pursuit of long-range anti-ship cruise missiles and rocket systems, it’s clear they are attempting to deny the United States the ability to operate freely in the region.”

The speech Secretary of Defense Mattis gave at the Shangri-La Dialogue on June 3 was arguably the most full-throated defense of traditional U.S. leadership that any Trump official has offered since the election. He spoke of the United States’ “enduring commitment” to the security and prosperity of the Asia-Pacific based on “strategic interests and on the shared values of free peoples and free markets.” He offered a “deep and abiding commitment to reinforcing the rules-based international order.” The speech was widely praised by delegates and was the talk of the conference.

And yet the cognitive dissonance of the messaging coming from the Trump administration was also confounding to the Asian audience. In the question-and-answer session after Mattis’ speech, an Australian delegate wondered if the administration’s rejection of TPP and the Paris Agreement, and its rough treatment of NATO, meant that Trump really wanted to deconstruct the rules-based international order. A Japanese parliamentarian questioned whether her nation’s security alliance with the United States was still based on common values like free trade, environmental protection and human rights. A delegate from Singapore wondered why the United States wasn’t more worried that China was aggressively filling the economic and trade vacuum left in the wake of TPP’s cancellation.

“As for the rules based order, obviously we have a new president in Washington, D.C. We’re all aware of that. And there are going to be fresh approaches taken,” Mattis answered, trying to frame the current American moment in a historic context. Of course there has long been a strain of isolationism in the body politic, a reluctance to serve as the world’s policeman. But after witnessing the carnage of tens of millions of people in World War II, Mattis noted, the “Greatest Generation” realized what a “crummy world” it would be if everyone just retreated back inside their own borders.

“Like it or not, we’re part of this world,” Mattis said, speaking for the change in America’s post-World War II mindset. “Even for all the frustrations that are felt in America right now and the sense that at times we carry an inordinate burden, that sense of engagement with the world is still deeply rooted in the American psyche.”

And then he paraphrased Britain’s World War II-era statesman Winston Churchill. “Bear with us,” Mattis told the Shangri-La Dialogue audience. “Once we’ve exhausted all possible alternatives, the Americans will do the right thing.”

_____

James Kitfield is a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of the Presidency & Congress and author of the recent book “Twilight Warriors: The Soldiers, Spies and Special Agents Who Are Revolutionizing the American Way of War” (Basic Books). He is a former senior correspondent for National Journal and has written about defense, national security and foreign policy issues from Washington, D.C., for more than two decades.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: