Trump's Gold Star controversy tramples on sacred ground

On a chill November day in 2010, a crowd of mourners gathered in Section 60 at Arlington National Cemetery, America’s Valhalla. The highest-ranking U.S. military officer to lose a child in combat in the post-9/11 wars was there to bury his youngest son, 1st Lt. Robert Michael Kelly, killed in action in Afghanistan. Sitting at gravesite 9480 next to his son’s wife, watching her accept the folded flag with the thanks of a grateful nation, hearing the report of the rifle salute and the sound of the bugler playing “Taps,” Gen. John Kelly was confronted with the same question that haunted the families of the more than 5,500 Americans killed in action in Iraq and Afghanistan. Was such unbearable sacrifice worth it?

At some point Kelly realized it was not for him to say. His son had already answered the question. “In his mind — and in his heart — he had decided somewhere between the day he was born at 2130, 5 September 1981 — and 0719, 9 November 2010 — that it was worth it to him to risk everything – even his own life — in the service of his country,” Kelly would later tell other Gold Star families. “So, in spite of the terrible emptiness that is in a corner of my heart and I now know will be there until I see him again, and the corners of the hearts of everyone who ever knew him, we are proud. So very proud.”

Ever since that day, John Kelly has striven to keep from politicizing his son’s death or making too much of it based on his own stature. Just days later, he insisted that the loss of his son not be mentioned when he gave a moving speech commemorating two other Marines killed in combat. He has discouraged questions about his loss even as he rose from commander of U.S. Southern Command to the head of the Department of Homeland Security for the Trump administration and to White House chief of staff. When approached by the Washington Post for a profile in 2011, he revealed a source of his reticence in an email: “We are only one of the 5,500 American families who have suffered the loss of a child in this war. The death of my boy simply cannot be made to seem any more tragic than the others.”

Just as he has so often trampled the traditional boundaries of civil-military relations designed to cordon the U.S. military from Washington’s hyperpartisan politics, President Trump this week thrust Kelly and his loss into the bright glare of controversy. Trump was asked by a reporter why he had been uncharacteristically silent for 12 days about the death of four U.S. Special Forces soldiers in Niger. During that time, Trump had tweeted incessantly about NFL players failing to stand during the national anthem. He had engaged in public feuds with the mayor of hurricane ravaged San Juan, Puerto Rico, and with Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker. In that stretch, Trump threatened the media for spreading “fake news,” and taunted the leader of North Korea. But no mention of the loss of four U.S. troops killed in a firefight with terrorists in Africa.

Replying to the reporter in typical counterpuncher mode, Trump attempted to elevate his own stature by denigrating others, falsely accusing his presidential predecessors of never or only rarely calling Gold Star families who lost loved ones. “If you look at President Obama and other presidents, most of them didn’t make calls — a lot of them didn’t make calls,” Trump said. “I like to call when it’s appropriate, when I think I’m able to do it.”

When the predictable backlash erupted against those false claims, Trump characteristically doubled down. In an interview with Fox News radio on the controversy, Trump offered up his chief of staff as evidence that Obama didn’t call families of fallen U.S. service members. “I think I’ve called every family of someone who died,” Trump said in a comment that was later disputed by a number of Gold Star families. “As for other representatives, I don’t know. You could ask Gen. Kelly, did he get a call from Obama?”

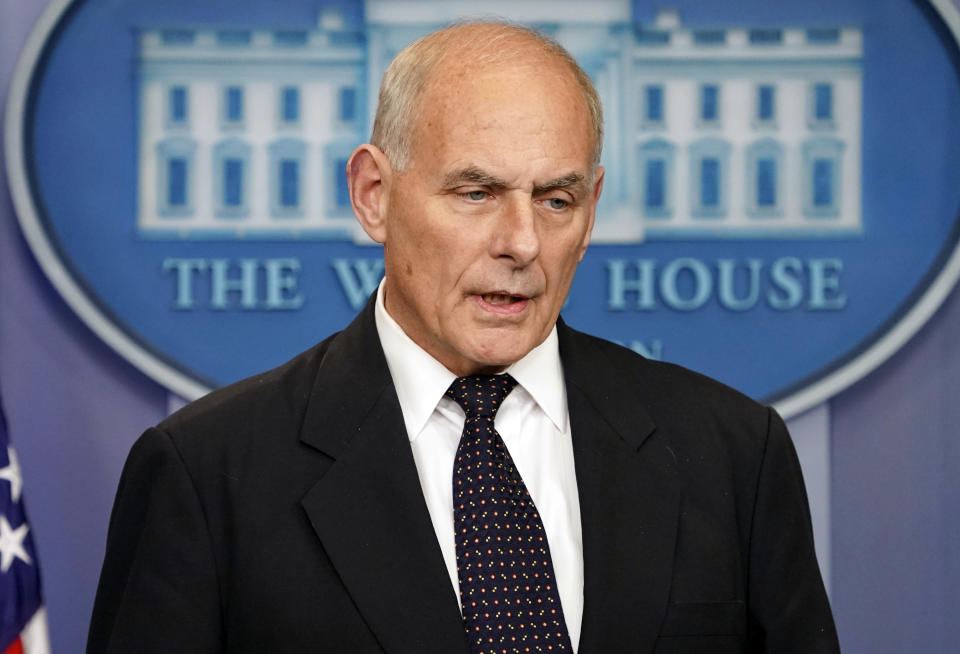

In an extraordinary press conference on Thursday, Kelly confirmed that President Obama did not call after the death of his son. That was not a criticism, Kelly said, and indeed he initially advised Trump against calling the families of the four soldiers killed in Niger because there was little he could say to ease their pain. When Trump called the widow of Army Sgt. La David Johnson, one of the troops killed in Niger, he reportedly told the grieving Myeshia Johnson that her husband “knew what he signed up for … but when it happens, it hurts anyway.” That was the account given by Rep. Frederica Wilson, D-Fla., a family friend who was with Johnson during the call and called Trump’s words insensitive.

Trump called Rep. Wilson a liar. Kelly said he was “stunned” and “brokenhearted” when he heard that a member of Congress had listened in on the call and made it public.

The bitter back-and-forth between Team Trump and its critics is already in danger of trampling one of the last plots of sacred ground in America’s increasingly charred political landscape. In truth, the need to console the families of fallen warriors is one of a commander in chief’s most difficult and emotionally draining duties. No two presidents approach the task in exactly the same way, and each brings to it their own unique interpersonal skills. Because the president is ultimately responsible for sending troops into harm’s way, there is inevitably an underlying tension in the exchanges, and the politics and policies of war always hover nearby.

“Because presidents sign off on the order putting troops in danger, they feel personally responsible for every death or injury that results, which makes calling on Gold Star families one of the most difficult things a commander in chief is asked to do,” said retired Lt. Gen. David Barno, who commanded U.S. and allied forces in Afghanistan. The willingness of partisans to exploit casualties for political gain, he noted, only adds to the pain of families who have lost love ones in combat. “It would seem Americans cannot even come together over our fallen troops anymore.”

Peter Feaver is a professor in security studies at Duke University who served on George W. Bush’s National Security Council staff. “I don’t think Trump helped himself with this controversy because you can never really win an argument with a grieving Gold Star family, but this is a fraught issue that every post-Cold War president has struggled with: How do you acknowledge the toll of war respectfully, and do so in a way that doesn’t overwhelm or even debilitate a commander in chief?” he said. “Because even when they go well these are emotionally overwhelming interactions.”

Bush met with a Gold Star family in 2004 on the same day as a presidential debate, Feaver notes, and fell flat in the debate because he was so emotionally drained. Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates wrote about the toll of writing the family of each service member killed in combat, and how it affected his willingness to stay in the job. Feaver believes that Barack Obama spent so much time with wounded veterans that it reinforced a tendency toward “hypercaution” about military deployments that persisted through his second term.

Nor do all the exchanges between commanders in chief and grieving families go well. Bill Clinton was criticized by some of the families who lost loved ones in the Black Hawk Down debacle in Somalia in 1993. After her son Casey Sheehan was killed in the Iraq War, Cindy Sheehan gained national media attention for an extended antiwar protest at a makeshift camp outside President Bush’s Texas ranch. The parents of two of the four Americans killed in a terrorist attack in Benghazi, Libya, in 2012 criticized Obama and later sued former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton over her role in the tragedy.

Investigations into the Benghazi attack marked the low-water mark in partisan efforts to turn tragedy into political gain. After spending more than two years and $7 million, the Republican-led House Benghazi Committee reached the same general conclusion as the seven previous U.S. government probes into the incident: No response to the attack would have enabled U.S. troops to reach the scene in time to save the four Americans. House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy alluded to the true target of the investigation in a 2015 interview with Fox News. “Everybody thought Hillary Clinton was unbeatable, right? But we put together a Benghazi special committee, a select committee. What are her numbers today? Her numbers are dropping. Why? Because she’s untrustable.”

Trump himself insisted that Benghazi was “bigger than Watergate,” and he tweeted about it scores of times. This week the left-leaning outlet Salon wrote that “Niger could be Trump’s Benghazi.” As Washington partisans unsheathe the long knives in their endless grapple, some may not even realize or care anymore that they are trampling over hallowed ground.

After having his personal pain exposed in the current controversy, John Kelly said he visited Arlington National Cemetery to clear his head and “walk among the finest men and women on earth,” some of whom were following his orders at the time of their deaths. “I still hope as you write your stories, and I appeal to America, let’s not lose this maybe last thing held sacred in our society — a young man or woman going out and giving his or her life for our country,” Kelly said at the end of yesterday’s press conference. “Let’s try and somehow keep that sacred.”

James Kitfield is a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress