Turned away by 2 countries, rescued refugees end their odyssey in Spain

VALENCIA, SPAIN — The first rays of dawn were just breaking through when the small speck was spotted in the Mediterranean’s turquoise waters off eastern Spain. It was the first of a three-vessel flotilla that for the past week has captured the world’s attention, triggering harsh words from European leaders, threatening to fracture alliances, provoking upheaval and illustrating how immigration, a polarizing topic in the U.S., is becoming the most fiery issue in Europe.

Shunned by other Mediterranean countries, the Aquarius rescue boat, accompanied by two Italian military vessels, was finally, after a week on the high seas, headed for port in Valencia, an elegant city famous for oranges, paella and its annual festival of Las Fallas, in which oversized effigies are set alight, covering the city in smoke. This weekend it was the site of a raucous gay pride festival with concerts and celebrations in all corners and spilling into the square in front of City Hall, which for days had been festooned with a banner: “Valencia: City of Refugees!”

On board the three ships were refugees from 26 countries escaping kidnappers, blackmailers, torturers, and groups such as ISIS and Boko Haram as well poverty and chronic food shortages. Many of the 630 onboard, including 100 children and teenagers and seven pregnant women, had come from West and sub-Saharan Africa, some trekking for weeks, some paying to cross in open trucks, having been recruited by shady agencies for nonexistent jobs. Some of those who set out on the journey died along the way as they crossed deserts where temperatures sometimes reach 120 degrees.

Slideshow: Rescue ship Aquarius docks in Valencia after weeklong odyssey at sea >>>

But after setting out onto the Mediterranean Sea, they found themselves the victims of the increasingly fraught politics of immigration, as a new government took control in Italy and reversed, in less than a week, that country’s long-standing policy of tolerance.

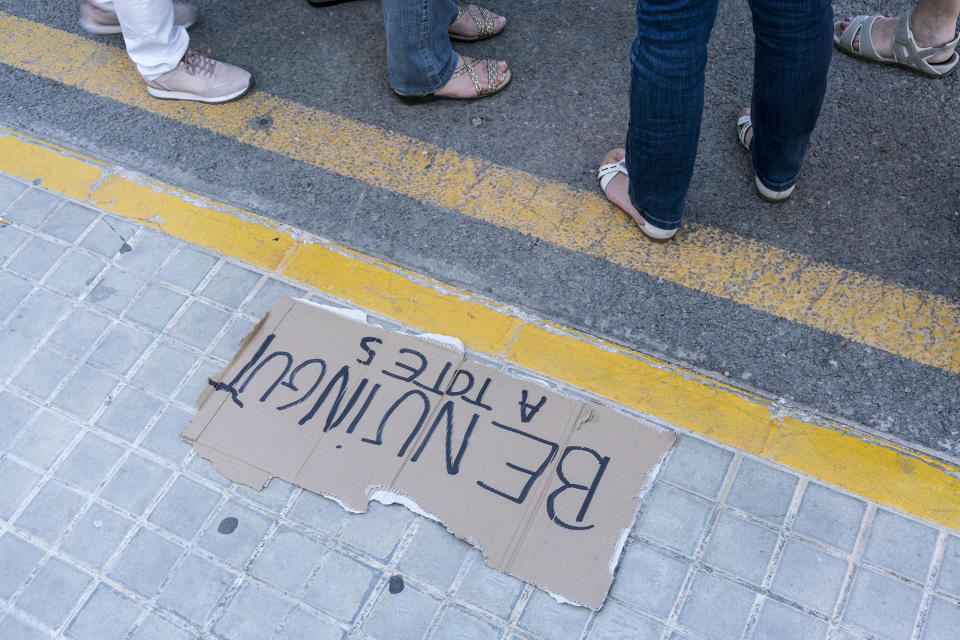

While hundreds of reporters from all over the world were kept waiting in a distant field from 5 a.m., the passengers came ashore near the dock for the luxury cruise ships that ply the Costa del Azahar (Orange Blossom Coast) to welcome signs in five languages.

They were met by translators of a dozen tongues, mask-wearing doctors and Red Cross volunteers. Their tales, as told to officials of Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières) and the rescue group SOS Mediterranée, the organizations that have plied the Mediterranean aboard the Aquarius since January 2016 and saved more than 30,000 refugees, were harrowing.

Wherever they’d started from, their first destination was Libya, which since the 2011 death of leader-for-life Moammar Gadhafi — who had accepted billions of Euros from the European Union to secure his borders and coastline against refugees trying to cross the Mediterranean — has become Africa’s main channel of escape to Europe. Once they reached that virtually lawless country, many of the refugees landed in detention centers, where they were subjected to beatings and rape, sold as slaves or forced into prostitution until relatives ransomed them. And having scraped together enough to pay smugglers the equivalent of hundreds of dollars for passage to what they thought was a better life, they were sent off on their own in small, overcrowded rubber dinghies with fake life jackets and little fuel, heading theoretically to the door of Europe — the rocky Italian island of Lampedusa.

In their flimsy vessels, many of those who set out never make it. Hundreds drown every week — some 10,000 perished in the Mediterranean between 2014 and 2016.

A week ago, rescuers spotted hundreds of refugees in distress off the coast of Libya, some clinging to the sides of their boats. More than 600 were brought aboard the 250-foot-long Aquarius, in a precarious operation in which two refugees drowned. Working in coordination with the Italian Coast Guard, the vessel was directed, as had been the practice, to Sicily — where the captain was stunned to learn that the new populist coalition government, then in power barely a week, would not allow the boat to dock. Specifically, the new interior minister — Matteo Salvini — leader of the hard-line anti-immigrant League party, blocked the arrival, saying Italy’s doors were closed to refugees. His views, says Annalisa Camilli, an Italian specialist on migration who writes for the Italian periodical Internazionale, reflect a growing divide over the past two years in Italy, where she says a recent poll showed that over half of citizens do not want to accept more refugees. “Italians feel abandoned by other countries in the EU,” who haven’t helped in taking in more refugees. “Relations are very tense, especially with France,” which instituted border controls after the terrorist attacks in 2015.

With Italy having taken in more than 640,000 refugees in recent years — more than 14,000 thus far in 2018 — Salvini directed the vessel to the European island nation of Malta, but its prime minister, Joseph Muscat, likewise refused entry. While Doctors Without Borders sent out furious communications about sick and injured passengers in need of food, water, hospitals and firm ground, Italy wouldn’t budge, ignoring pleas from other EU nations.

Finally the Spanish government of Socialist Pedro Sánchez – itself barely a week old – stepped up and offered the vessel safe haven. And though Doctors Without Borders pleaded for Italy to allow the passengers even a brief respite on land before the four-day journey to Valencia, the Italian government refused — though it did authorize the delivery of oranges and water and provide a Coast Guard vessel and a warship to relieve the crowding on the dangerously overloaded Aquarius.

Spaniards, while largely sympathetic to the plight of the refugees, are themselves divided on the hospitality of their government, which has offered the refugees medical aid and possible asylum; unofficial newspaper site surveys show some two-thirds opposed. “It’s one thing to be generous if your country is doing well,” said a taxi driver en route to the port. But Spain, she notes, is still recovering from the devastating economic downturn that began a decade ago and sent unemployment to nearly 30 percent at its worst.

Many believe that after their horrifying journey to Spain, the majority of the refugees will end up back in the countries they first left. “I think most will be deported,” said Irine Pasqual, an electronics worker in her early 30s. She speculates that the Pedro Sánchez government may be hoping to win sympathy from the European Union and redeem the country’s reputation, which was tarnished last fall when the previous right-wing government of Mariano Rajoy used violence to shut down an unauthorized referendum on secession by the province of Catalonia, with its government seat in Barcelona.

Even those whose applications for asylum the Spanish government deems credible —typically less than half who apply for it — may not find the land of milk and honey they dreamed of. “People get stuck here,” notes photographer Laura Silleras, who has worked with refugees. While she notes that the Spanish government provides housing, Spanish lessons and a small stipend to refugees, it comes with a time limit. “If after a year, they haven’t figured out a life here, the government cuts them off — then what are they supposed to do?”

Others point out that Spain’s detention centers are substandard and that the country hasn’t yet accepted thousands of Syrian refugees and other asylum seekers it promised to take in two years ago. The European Union, meanwhile, keeps putting off a decision on a comprehensive plan for dealing with refugees, promised for this summer; last week, most parliamentarians didn’t bother showing up for the immigration debate, or walked out during it. Countries such as Sweden and Germany — the latter of which discovered that less than 10 percent of recent immigrants had found work — have taken the dramatic step of paying immigrants as much as $2,000 to return to their countries of origin.

Oddly, the International Organization for Migration notes that the actual numbers of people leaving Africa for Europe are down. According to Camilli the number has dropped nearly 80 percent since Italy — even before the recent change of government — began controversially training and paying the Libyan coast guard to block the refugee flow by force. That practice is now facing legal pushback.

The EU must do all it can to promote peace and economic development in Africa, warned the president of the European Parliament, Antonio Tajani, or “we will see migratory flows of biblical proportions — not thousands but millions moving from Africa.”

But while Europe experiences a panic attack, Spain appears to be taking its normal “ma?ana, ma?ana” approach, going paso a paso, step by step. The travelers aboard the Aquarius arrived safe and sound, if weary, and despite the tumultuous journey, the rescue mission was ultimately a success, declared Doctors Without Borders on Sunday. In a sometimes spirited and emotional hourlong joint press conference held at the port building Veles I Vents, staff of Doctors Without Borders and SOS Mediteranée expressed their frustration and incredulity at what had been an unnecessarily harrowing operation. They denounced the actions of Italy and Malta, and the inaction of the EU. “Europe has lost its moral compass,” said Dr. David Beversluis, who’d been aboard the Aquarius. They condemned Italy’s ongoing support — with EU complicity — of the often brutal Libyan coast guard, which they said tries to divert rescue boats such as the Aquarius. They disputed accusations that their rescue missions only enable and encourage illegal immigrants. “We are not the cause of this,” said Karline Kleijner, emergency manager for Doctors Without Borders, “nor are we the solution. We are merely a symptom of a failing [immigration] policy. Saving lives,” she concluded, “is not a crime.”

Outside the building, spectators sat at an outdoor bar, engrossed in a soccer match, while music from the ongoing Gay Pride Festival blasted across the port.

As to what will happen to the rescued refugees, nobody is sure.

Mayors across Spain have offered to take in dozens of families — Barcelona’s left-leaning mayor, Ada Colau, offered refuge to all of them — and Catalonia’s new president offered to take in some 1,200 more. And in a shocking reversal of recent policy, France — where President Emmanuel Macron railed against Italy’s recent move, and which shut its own doors to refugees three years ago — welcomed asylum seekers from the Aquarius who would prefer to move there.

The White House has not issued a statement on the situation.

Melissa Rossi, a writer based in Barcelona, is the author of the geopolitical book series “What Every American Should Know.” (Plume/Penguin).

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: