'Warriors': MSCS leader Toni Williams on her mother's battle with sickle cell disease & her legacy

The Memphis-Shelby County Schools Board of Education work session on Feb. 20 began like most others. Board members and interim Superintendent Toni Williams took their seats at the front of the auditorium, while MSCS staffers and community members filed in.

The agenda included the usual items that needed to be discussed: the board chair’s report, the superintendent’s report, proposed policies, and an array of potential contracts.

But it wasn’t long before Williams deviated from the standard routine and began talking about her mother, Shirley Yvette Greene, who had passed away in July at the age of 58, after a lifelong, hard-fought battle with sickle cell disease.

For Williams, this was unusual. She rarely discussed her personal life in a public setting. At times, MSCS communication staffers had said to her, “You never show anything personal about you; people don’t know who you are.” Williams hadn’t even told colleagues when her mother was on life support late in the summer.

But there she was, talking to an audience about her mother’s private fight against a merciless blood disease.

“My mother was a woman of grace, fortitude, who battled against the relentless grip of this disease,” Williams said during the meeting. “I want to give you a glimpse of what a sickle cell warrior looks like.”

Everyone watched as a video began to play on the auditorium’s projection screens. They saw clips and photos of Green that detailed her struggles with sickle cell disease and listened to a recording of Williams as she spoke about her mother’s strength in the face of adversity.

More: Who is Marie Feagins? What a former colleague and student said about the next MSCS leader

As the video played, Williams did her best to stay composed. Being this vulnerable wasn’t easy for her. But she was determined to honor her mother ― in more ways than one.

After showing the footage of Green, the video’s focus shifted, and it began to show clips of MSCS students who also had sickle cell disease.

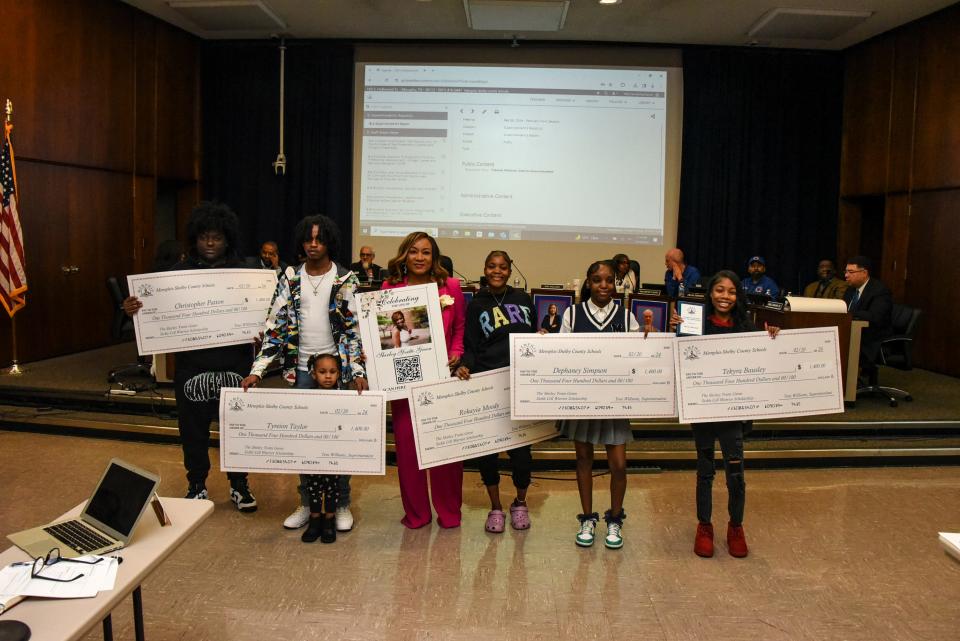

These students were in the auditorium, and when the video ended, Williams welcomed them and their families up to the front, announcing that they were recipients of a new, $1,400 award named after her mother: the Shirley Yvette Green Sickle Cell Warrior Scholarship.

It was a fitting name for students who had shown resilience against a ruthless disease. To Williams, they were warriors ― just like her mother.

What is sickle cell disease?

Sickle cell disease is a severe, genetically inherited blood disorder that predominantly affects African Americans. The American Society of Hematology has estimated that 8% to 10% of African Americans have the sickle cell trait, and a National Library of Medicine Study calculated that 93.4% of the patients hospitalized for sickle cell disease from 2016 to 2018 were Black.

Whereas normal red blood cells are disk-shaped, flexible, and easily able to move through blood vessels, blood cells with sickle cell hemoglobin are stiff, sticky, and crescent-shaped. Sticking together, they struggle to move through blood vessels and can block the movement of healthy, oxygen-carrying blood.

Put simply, the disease interferes with the delivery of oxygen to the tissues ― and this can wreak havoc on the body of those with sickle cell. They’ll have bouts of excruciating pain, hospital trips are frequent, and their life expectancies are usually shorter. A 2023 study in the publication Blood Advances put the life expectancy for a publicly insured individual with sickle cell disease at 52.6 years.

When Williams’ mother was growing up, it was even shorter.

The daughter, the caretaker

In 1985, the year she was supposed to die, Green gave birth to Williams.

She was 20, the age doctors had initially said she wouldn’t exceed because of sickle cell disease. They were nearly right.

Giving birth to Williams, Green flirted with death; the situation became so perilous that blood for her had to be flown in from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But she lived and continued to defy predictions. Each year was a reason to celebrate, but life wasn’t easy, and sickle cell disease continued to take its toll on Green.

There were different levels of pain. Sometimes, she’d just feel numb or sore. Then, sometimes she’d feel like someone was stabbing her with a knife all over her body, and a young Williams would listen as her mother screamed in agony.

It was hard for her to hear, and at an early age, Williams decided she would be a caretaker for her mother. During Green’s stays in the hospital, Williams would be right by her side, reading to her. The nurses would look in and say, “There’s Shirley, and there’s Tu Tu," Williams' nickname.

More: This Memphis area hospital is giving high schoolers an inside look at healthcare jobs. Here's how.

But while Williams saw herself as a caretaker, Green didn’t. To her, Williams would always be her child.

“Her number one job was, “I’m your mother,” Williams said.

Showing resilience

Green felt strongly that she should be taking care of Williams; it wasn’t supposed to be the other way around. She often didn’t even want her daughter to know she was sick ― she didn’t want anyone to know she was sick.

Green was determined not to let sickle cell disease be the defining factor of her life and she worked hard. When Williams was young, Green owned a hair salon, and she would wake up at 6 a.m. and work until close to midnight. She was a fun, jazzy mother who wore stylish clothes.

And every time sickle cell disease knocked her down, she got up and punched back. She ate healthily and exercised. She kept track of which medications were effective, often educating the doctors on what was working and what wasn’t. She would drive herself to the emergency room, rather than ask someone else. When she was in the hospital wrestling with dreadful pain, she would say, “God, when I get up.”

When she was discharged and wheeled out, she’d tell officials that her “ride was waiting,” then sneak off, get in her car, and drive home. It wasn’t long before she’d be back at work.

Green was a fighter ― and learning from her mother, Williams became one too.

“You’re beautiful,” Green told her daughter. “But being pretty is nothing. Try to be smart.”

Williams did.

Motivated by her mother, Williams excelled, graduating from Whitehaven High School, and earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in accounting from Clark Atlanta University. She launched a successful career in finance, and in 2019, she was named chief financial officer of MSCS.

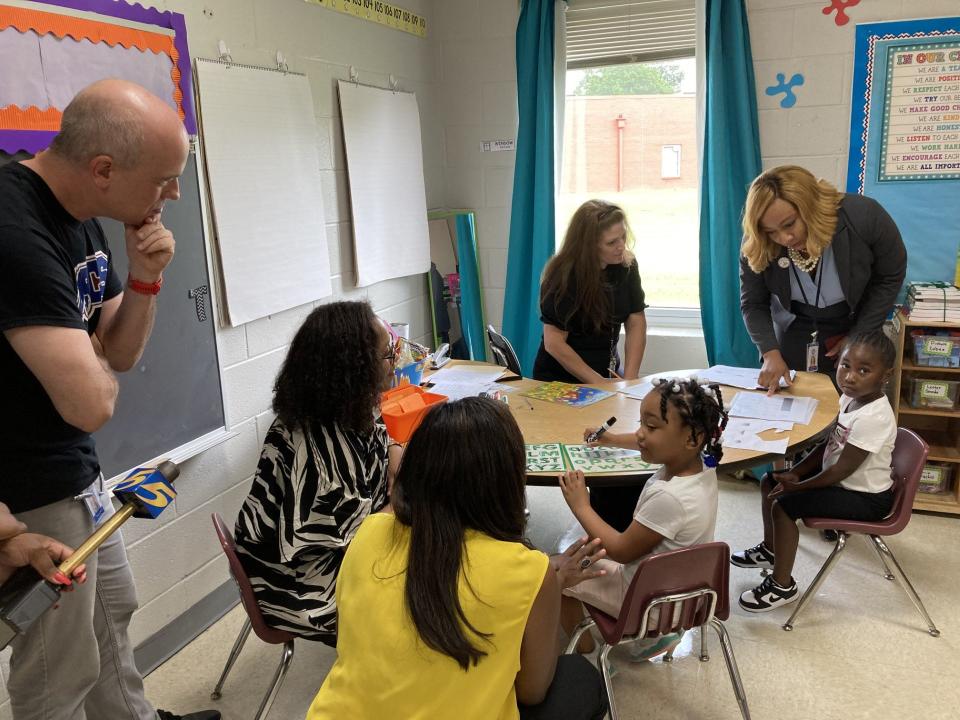

Then, in August 2022, she was tapped to be interim superintendent, after Joris Ray resigned amid an investigation. The promotion would place her in charge of the largest school district in Tennessee, one with around 100,000 students and 14,000 employees.

The demands of the job would also give her less time to spend with her mother.

“If I look back over my superintendency, I'm proud, but there's a sacrifice to this role,” Williams said. “I look, and my biggest sacrifice is not having the time to pay attention to her.”

What was hidden

As Green entered her late forties and early fifties, her physical condition worsened. She continued to valiantly fight back against sickle cell disease. She remained meticulous about her diet, exercise, and medicine. But decades of battling against the unforgiving illness took a toll on her body.

Her lungs were scarred; had you looked at an x-ray of them you would have thought she was a smoker ― but she had never smoked a cigarette in her life. She had to have her gallbladder removed, suffered several minor strokes, and developed an irregular heartbeat.

As an adult, Williams saw herself as a caretaker more than ever. But Green still saw herself as a mother first. Williams was her daughter, and she didn’t want to burden her. Often, she wouldn’t tell her when she was in the emergency room, and only call Williams if she wasn’t receiving adequate care ― at which point she would arrive swiftly and advocate for her.

More: Memphis-Shelby County Schools sets start date for new superintendent

When Williams became interim superintendent, she believed Green hid things about her health from her. After all, Williams had stepped into one of the most important jobs in the city, perhaps the state ― she didn’t want to trouble her with her health issues.

“She was so focused on hiding things from me, and dealing with it herself,” Williams said. “She did not allow me to know she was frequently in the hospital.”

But Williams did know that her mother was in the hospital in late June, not long after the board had voted to extend her tenure as interim superintendent. Something seemed different about her. She wasn’t screaming in pain, as patients in sickle crises often do. She was quiet. Though clearly still hurting, she was unconscious.

Something, Williams thought, was not right. But she told herself her mother would be fine.

Two weeks later, Williams wore a pink suit on Live at 9, News Channel 3’s morning show. Williams texted her mother about it, and Green responded, saying, “Wow, you did a good job.”

It was the last time Williams would talk to her.

Saying goodbye

Later that day, Williams got a call. Green was having a seizure, an unusual symptom for her. She was moved to the intensive care unit and put on life support. Two days later, an MRI showed that she was completely brain dead. She had had two major strokes.

Williams stayed next to her mother while she was on life support, taking district phone calls by the hospital bed and keeping her hand in her mother’s. She attended a school board work session, not telling people what was happening, then returned to the hospital.

At first, she had determinedly told the doctors, “She’s going to stay alive, and you’re going to wake her up.” But she also saw her mother suffering. She saw her on a ventilator. She knew it was time to say goodbye.

“With everything I know about your mama and the warrior that she is,” a longtime family doctor gently told her, “She wouldn’t want to live like this.”

After about a week and a half, Williams and her family took Green off life support. And when they did, her vital signs started to creep up. The fighter was fighting, one last time.

“I need you to talk to her,” the nurse told Williams. “You’ve got to talk to her because she’s not going to leave without you talking to her. She needs to know that you’re going to be okay.”

So, Williams gingerly took her mother’s hand and spoke.

“Mama, it’s time to rest. You have fought, and you’ve done well,” she said. “I’m extremely proud of you… It’s time to rest.”

As soon as Williams said this, Green’s vital signs went back down. She looked at the nurse.

“Is that it?”

The nurse replied: “She’s gone.”

'On a personal note...'

For six months after her mother’s death, Williams cried before every board meeting. She had always called her on the phone before them, and now she couldn’t. The tears would come, and she’d listen to gospel music to soothe herself; a favorite song was “I Know the Lord Will Make a Way.” Then, she would take her seat in the meeting, surrounded by board commissioners, and begin to speak.

“Hi, Memphis-Shelby County Schools family…”

More: Memphis high school receives musical instruments, $40K gift from foundation, Grammy-nominated singer

She had inherited her mother’s impressive collection of clothes and had wanted to sell it to raise money for sickle cell patients. But every time she looked through her things, she’d fall apart.

“You see me as a superintendent,” she said. “But on a personal note, during this journey on my superintendency, I’ve been dealing with my mom’s death.”

Williams still hasn’t completely worked through her grief. At times, she wrestles with feelings that she might have paid more attention to MSCS than her mother. She didn’t know what Green was going through, of course. But she feels like she should have known.

The five MSCS students who received the new scholarship named for her mother have given her strength ― and to an extent, they’ve helped her heal.

“I can't change the last 18 months ― and I get shaken up by this or just emotional ― that I was paying more attention to the district in some respects than I was paying to my mom,” she said. “I can't take that time back and replace it. But I can honor her legacy and life through our students.”

'I don't want my disease to set me back from anything'

The $1,400 scholarships could just be the beginning. Marie Feagins is slated to become the permanent superintendent of MSCS on April 1, and when Williams transitions out of the role, she plans to do more for the recipients ― recipients that remind her of her mother.

The Commercial Appeal spoke to three of the students who received the scholarship, and while all of them spoke candidly about their struggles with sickle cell disease, they also were optimistic about the future. They had endured suffering that was almost unimaginable, and been to the hospital time and again ― yet they were still setting goals for the years to come, talking about how the scholarships would help them pay for books and school.

One of them, Tyreion, a Memphis Virtual School student, spoke of how he had learned to better express himself and take care of himself more effectively. Tekyra, a student at Whitehaven High School, and Dephaney, a student at Trezevant High School, both emphasized how determined they plan to go to college.

Tekyra even noted that thanks to dual enrollment classes, she already has enough course credits to skip a year in college. She wants to eventually work in the medical field and help other people with sickle cell disease.

“I feel like the fact that I have sickle cell makes me want to be successful even more,” she said. “I don't want my disease to set me back from anything.”

It’s no wonder Williams sees similarities between these students and her mother. In many ways, Tekyra, Tyreion, Dephaney, and the other recipients are like Green.

They are strong. They are resilient. They are courageous. As Williams put it: "They are warriors."

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: MSCS leader Toni Williams establishes sickle cell student scholarship