He went to prison for Jan. 6. Now he's running for Congress. How do voters weigh insurrection?

CHARLESTON, W.Va. — On a college campus near the Kanawha River, dozens of residents, several wearing patriotic-themed colors or “Make America Great Again” shirts, walked past an RV bearing the image of Michael Flynn, a key figure in the effort to overturn the 2020 election.

Inside a brick building, they waited to see a film about the former general and Trump administration national security adviser – who pleaded guilty for lying to the FBI and was later pardoned – portraying him as a hero unjustly persecuted by the “deep state.” In the hallway, a banner that traveled with the show displayed a wall of shadowy photos and headlines, with a spiderweb of lines and simulated push-pins that intimated conspiracy.

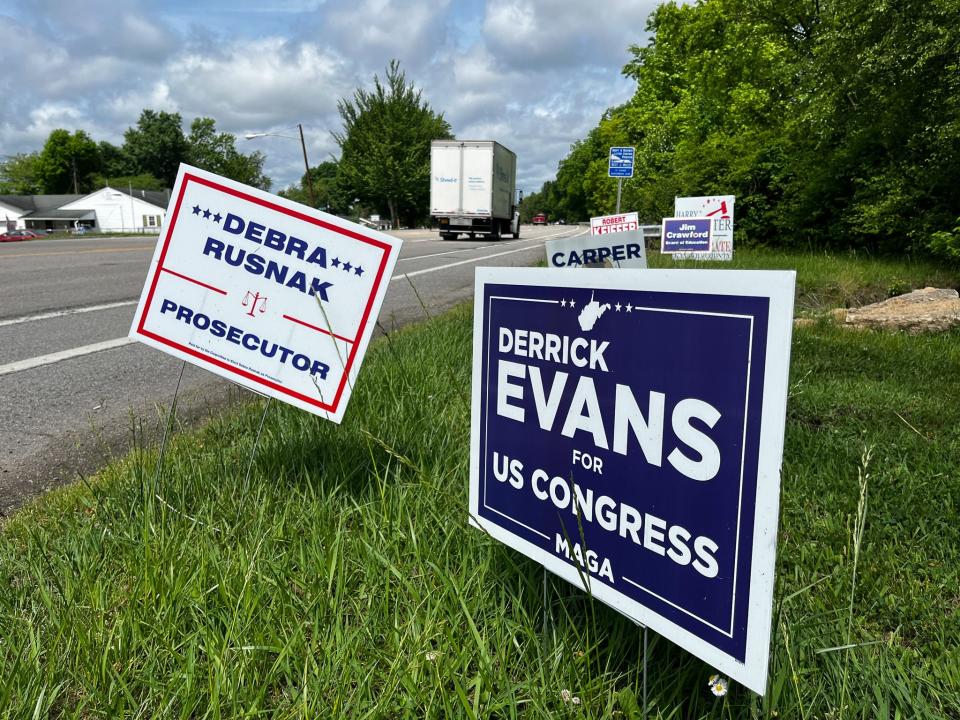

But Flynn’s screening in rust-belt Charleston served another purpose – highlighting his endorsement of Derrick Evans, who was running for the GOP nomination for U.S. House on his own story of political persecution.

Evans, 39, served three months in prison after joining pro-Trump protesters who invaded the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. That day, he had yelled, "We’re in! Derrick Evans is in the Capitol!” as he live-streamed crowds trying to stop Congress from certifying the election of President Joe Biden.

At the time, he had been a freshly elected West Virginia state lawmaker. Facing prosecution, he apologized and resigned from his post. But in this election cycle, he has proudly fashioned himself a “J6 political prisoner,” presenting his conviction as an ultimate MAGA credential in hopes of winning the GOP primary in the once-blue coal state turned reliably red.

It was Wednesday night, less than a week before the May 14 primary election, which could essentially decide who takes the House seat in Republican-heavy District 1. Amid gathering national attention – and national characters like Flynn – the race had become a key test of voters’ conclusions on Jan. 6, the event that cut a new dividing line through American politics.

Evans, a real-estate investor, is among dozens of people who participated in the riot in some capacity and have sought election to everything from school boards to Congress. This year, others include U.S. House candidate Chuck Hand, who is running in a Georgia GOP primary.

Then there is former President Donald Trump himself, still awaiting several trials including one on federal charges that he tried to steal the 2020 election. He has framed the Jan. 6 participants as patriots and suggested that if he retakes the White House, he could pardon them all.

Evans, and candidates like him, count on an electorate that sees the insurrection in the same light.

"When they find out that I'm the elected guy who got arrested for January 6, they shake my hand and they thank me and tell me they're gonna vote for me," he told USA TODAY.

Darlene Rose, who attended the screening, said she was drawn to vote for Evans by what she views as an unfair sentence that strengthened his political resolve.

“They put him in jail for no reason whatsoever, just because he was down at the Capitol,” she said.

Whether that message resonates widely enough to topple incumbent Carol Miller – herself a pro-Trump Republican, among the 147 in Congress to vote against certifying the 2020 election – is an open question.

Several West Virginia political observers downplay the likelihood Evans can best Miller, a Huntington bison farmer, in what’s expected to be a low-turnout primary on Tuesday.

Yet Evans has had at least some encouraging signs, including raising more campaign funding than some expected and winning an endorsement from Rep. Bob Good, R-Va., chairman of the House Freedom Caucus.

An upset win could leave Congress to grapple with how or whether to employ the Civil War-era 14th Amendment, meant to bar insurrectionists from taking office.

For Evans, however, such questions are easily answered by his views about the meaning of Jan. 6: It was simply the moment he had “the courage to stand up and speak out against a stolen election.”

More: His father founded the Oath Keepers, went to prison. He's running for office as a Democrat

Jan. 6 connection could draw voters, or repel them

Days ahead of the election, Jim Umberger, who is running in the Democratic primary for the District 1 congressional seat against Charleston resident Chris Bob Reed, wound his pickup down a two-lane rural road near Leslie. It’s a rural area dotted with closed churches and abandoned homes. The 74-year-old retired health administrator and Vietnam veteran was looking on a map to knock on doors of registered Democrats.

It was a lonely job.

The state’s Democratic supermajority, once powered by coal mining unions, has shifted to a Republican one. Its last Democratic senator, Joe Manchin, isn’t running for reelection when his term expires next year. Trump won every county in 2020.

Soon Umberger was talking to a retiree through a screen door on a porch fitted with security cameras. She said she had to install them all to ward off thieves, in a state that has suffered one of the nation’s worst drug epidemics.

Her top concerns were battling addiction and the need for more jobs, she said. As for Evans? That’s a no, she said. Jan. 6 made her sick.

“I’m ex-military; I hold the belief that this is the greatest place going. And to see that, I was just appalled,” she said.

Back in his truck, Umberger said the prospect of running in the general against Evans initially appealed to him, since his stance on Jan. 6 “may be a bridge too far for a lot of people.” But he also worries that Republicans who downplayed the riot have helped change such views.

In January, a USA TODAY/Suffolk Poll showed sympathy for the rioters has increased among the voting public, despite more than 1,250 people having been charged in the attack.

The percentage of people calling rioters “criminals” dropped from 70% two weeks after the attack to 48%. Nearly a third of those surveyed said the convictions and sentences for hundreds of people for their role on that day were inappropriate and should be overturned.

When Evans was arrested at his home in the 450-resident town of Prichard just days after the riot, he was condemned by many state leaders, including Gov. Jim Justice. He resigned the House of Delegates seat he’d won in November 2020 and expressed regret, WDTV reported.

But after Evans's release, he ramped up criticism of such prosecutions and spoke about his experience. He wrote a book titled “Political Prisoner: The Untold Story of January 6th,” deciding to try to return to the Capitol as a congressman.

“What I think has changed is that those people who really believe that the insurrectionists were saving the country and that the election had been stolen are now given a newfound legitimacy because of the changing verbiage that's coming from Trump and others supporters,” said Marybeth Beller, a political science professor at Marshall University.

But she doesn’t think it has changed minds about whether it was acceptable. And she said the debate over Jan. 6 has faded from the public eye and receded in significance for many everyday voters.

Chris Trent, a Logan County Republican, said most establishment Republicans support Miller, who emphasizes that she is pro-Trump. But he’s not surprised that at least some anti-establishment GOP voters, especially those frustrated at the lack of progress in addressing the state’s drug epidemic and or significantly boosting its economy, are drawn to Evans.

“From the people I speak to, Mr. Evans being charged over the January 6th stuff brings him more support than he would have had without those charges,” he said.

In October, a WV Statewide News Poll showed that Evans making gains from three months earlier, rising from 38% to 44%, while Miller fell from 62% to 56% support. And while Miller has outraised Evans, his fundraising hasn’t fallen too far behind. As of April 24, election filings showed he had raised $781,505 compared with her $977,031.

Still, Evans remained a relatively minor figure in Jan. 6 compared to Miller’s well-known name – recognition buoyed by her son Chris Miller’s run for governor. She likely has a better “ground game” in population centers, said Sam Workman, director of the Institute for Policy Research and Public Affairs at West Virginia University.

And Beller noted that two years ago, Miller won 66% of the vote in a five-candidate primary before winning a third term.

In email answers to questions, Miller said voters are more concerned about inflation – prices at the gas pump and grocery store – and issues like election security and illegal immigration.

Asked what Miller thinks about Evans' participation in the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol and if that should disqualify him from serving in Congress, she did not directly answer but responded: “I don't think about him at all.”

More: Calif. statehouse candidate says she didn't join Capitol riot. Video shows otherwise

Can a Jan. 6 participant be elected to federal office?

In downtown Charleston, across town from the gold-domed state Capitol, residents ducked into an early voting site in an election office on the ground floor of a parking garage, its glass windows reflecting the lights of a police car parked just outside.

Voters who spoke to USA TODAY cited a mix of concerns driving them to the polls: Inflation, coal’s decline and worries about U.S. border security. One woman complained of having to choose between Democratic “sheep” and Republicans who had “drank the MAGA Kool-Aid.”

Retiree Ken Sullivan, a Democrat, said he worried about threats to democracy and right-wing candidates on local boards. Asked about Evans, he said, “I can’t imagine a guy with that reputation” would prevail.

But if he did, could he even serve?

In West Virginia, voting laws strip convicted felons of the right to vote until sentences are completed, including probation and parole.

Despite his conviction – which came with a three-month prison sentence and 36 months of supervised release after he admitted that he “committed or attempted to commit an act to obstruct, impede, or interfere with law enforcement officers” and that he obstructed a federal function – Evans has contended that he can hold office.

But the group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, which has worked to challenge Trump’s appearance on primary ballots based on Jan. 6, has argued that Evans should have been kept off the ballot and would be disqualified from holding public office under a section of the 14th Amendment because of his conduct.

It applies to people who previously served in federal state or local office and took an oath to uphold the Constitution and then participated in an insurrection, according to UCLA law professor Rick Hasen, director of the Safeguarding Democracy Project. Such an oath is required of the state office Evans won in November 2020 and briefly held.

But it would be up to Congress to enforce the 14th Amendment, Hasen said, and it’s not clear if members would need to pursue it through a statute or by refusing to seat a representative they believe is disqualified.

Workman, of West Virginia University, said any attempt to challenge such a candidate’s seating in Congress would likely wind up before the Supreme Court – if it made it that far. He doubts a majority Republican House would attempt to enforce it.

The past quarter-century in politics, he said, has shown that rules and laws often amount to social norms that can be obeyed or not.

“The two parties’ internal dynamics are the center of our politics and politicking much more than our older debates over law, rules, or written policy,” he said.

With just days to go before the primary in West Virginia, Evans predicted he would prevail in any battle to block him if elected. He also cited a higher authority.

“Our rights do not come from the government, our rights come from God, our creator,” he said.

As his advisers hovered around him at the college campus interviews with what he called the “fake news media,” Evans said he was glad to be running his campaign in West Virginia, where he said people are critical thinkers, in contrast to “CNN parakeets” in blue cities.

Dipping into often-repeated phrases, he vowed to refuse to “play patty-cake politics” in his fight against political “swamps” and a corrupt “deep state” that he says victimized him.

“It wasn't until the illegitimate Biden regime and the weaponized deep state came to my house, and ripped me away from my family and drug me to the middle of the swamp that I looked around and said, I'm gonna have to fight my way back out of the swamp. So I decided, you know, what, they came to my front door, I'm gonna run for Congress and take this battle to their front door the same way they brought it to mine,” he said. “They picked this battle.”

He added, “If I win the election, oh boy, we're gonna have some fun.”

Evans, wearing jeans, boots and a sport coat, walked across the grassy campus to the building hosting the Flynn movie.

It was part of a national tour where guests paid $35 for the movie or could buy a $200 VIP ticket that included a photo-op with Flynn and gifts such as a Flynn book, a movie poster and collector coin. Several reporters arrived for the event, having gained permission from the film company to attend.

Just before the film started – and before anyone could ask about his support of Evans – Flynn demanded that the media be thrown out.

Chris Kenning is a national correspondent for USA TODAY. Contact him at [email protected] or on X @chris_kenning.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Derrick Evans' West Virginia congressional bid is a test of Jan. 6