What the polls can't tell you about the coming campaign

Other than a signed contract with Donald Trump, there may be nothing as worthless in the world as a presidential poll 18 months from an election.

All of us who work in the political media know this, or should anyway, and yet we continue to conduct these polls and dissect them. I guess that’s because we need something to talk about, or more likely because we can’t think of any way to make sense of a political campaign that doesn’t resemble baseball’s power rankings or an NCAA bracket.

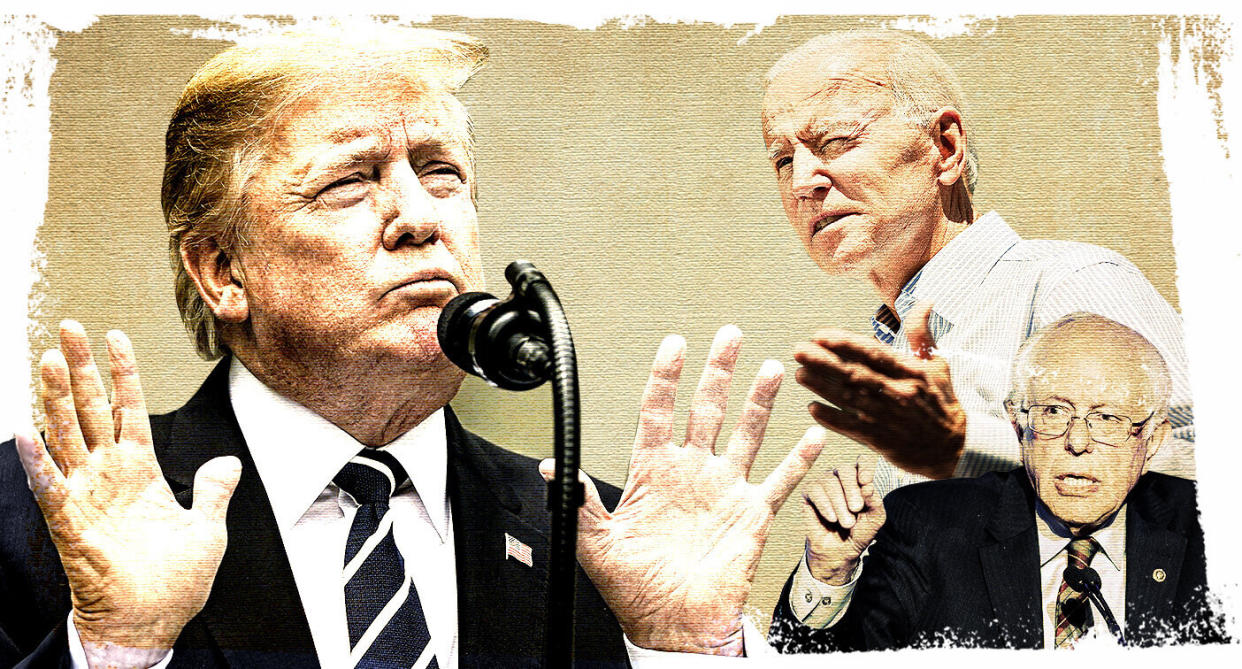

And so everyone knows by now that Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders are way ahead of everyone else in the crowded Democratic field, which is right up there with other irrelevant stuff, like the revelation that bedbugs have been around since the dinosaurs, or Scarlett Johansson’s engagement, or Bill de Blasio.

Your basic national poll at this nascent stage of a campaign is really just a reflection of name recognition and media attention. A more detailed poll, the kind more likely undertaken by campaigns than by media, might tell you which obstacles will be hardest for a candidate to overcome in the public mind, or what assets about him or her are most valuable. But in terms of predicting results, you might as well bust out the Magic 8 Ball and start shaking.

At this time in 2007, a lot of polls would have told you not just that Hillary Clinton was a lock for the Democratic nomination (she wasn’t), but also that Rudy Giuliani would be her opponent.

(Yes, the same Rudy Giuliani who now appears regularly on your television sounding like the great-uncle who everyone swears was a big success back in the day, but who now hangs around the open bar at family weddings spouting conspiracy memes from Facebook.)

The problem is that while voters generally knew who Giuliani was and liked what he stood for well enough, voters in the early primary states preferred someone more, you know, nice. And what always happens in primary campaigns is that as soon as the earliest votes are cast, the polls everywhere else start to shift dramatically, as voters recalibrate their idea about who’s viable and who’s not.

Giuliani ended up winning exactly zero delegates, which, as you might imagine, dealt a significant blow to his chances.

At about this time in 2015, people in my business were proclaiming Scott Walker the emerging frontrunner for the GOP nomination, based on a bevy of credible national polls. Walker matched Giuliani’s total exactly.

I guess you could say that state polls are more relevant, especially in Iowa and New Hampshire and South Carolina. And they will be, for sure, once voters in those states start seeing candidates for the second and third times and thinking more deeply about the approaching primaries. That’s probably around October.

For now, though, the state polls are mostly just mimicking the national polls, because voters there are focused on the end of school and the start of summer, just like the rest of us.

In other words, the whole polling thing right now is really just a hall of distorting mirrors, and I’d expect both Biden and Sanders to fall back among the pack as the campaign becomes less of an abstraction.

But the deeper problem is that, in a race with at least 23 candidates, at least 15 of whom could fairly be called serious, polls don’t measure the main factor that will determine the shape of the field.

The traditional (and hopelessly clichéd) metaphor for a presidential campaign is, of course, the horse race. In that model, one or two candidates jump out to the head of the pack at some point, and everyone else tries to catch them.

With this many candidates, though, the horse race conceit doesn’t really fit. The best metaphor I can think of is a reality show competition, like “The Voice” or “American Idol.”

Slowly but steadily, candidates will start to face elimination, either because they have no momentum or no money, or both. And the question isn’t who can amass an insurmountable lead, as in a horse race, but rather which contestants can build a solid enough base of support to avoid elimination and move on to the next round.

In a campaign like this one, it’s not the level of broad interest in a candidacy that matters most, but rather the narrow base of unshakable support that can keep it afloat. It’s about staying power, which polls don’t really measure.

The best example of this is Trump’s campaign. By July of 2015, Trump was taking over the lead in national polls, and, contrary to what I thought would happen, he never relinquished it.

The mistake I made then, having covered a lot of “horse races,” was to assume that commanding 25 or 30 percent of the vote wasn’t enough to win the nomination. Which was true in a traditional field of six or seven candidates, but not when there were a dozen of them divvying up the same establishment-minded vote.

What mattered is that Trump was a celebrity and that he had stumbled on a single resonant issue — immigration — that energized a pocket of conservatives. His 25 percent wasn’t going anywhere, whereas everyone else struggled to consolidate a reliable base of support.

In the end, Trump didn’t so much squash the other Republicans as outlast them.

That’s going to be even more the dynamic among Democrats this year. First of all, they’re in a contest where delegates will be awarded by proportional voting rather than a winner-take-all system, which means that a candidate with modest but passionate support can rack up plenty of convention votes even without winning states outright.

And for right now, at least, most of the candidates don’t have so-called super-PACs, for fear it will offend good-government liberals. That means only a candidate with a highly motivated core of supporters will be able to raise enough money to last.

If I’m a Democrat running in this environment, my goal isn’t to be among the top three or four in national polls by the fall (although sure, that would be nice). My goal is to solidify 20 percent of the vote and hold it into next year, when the field will narrow.

Who can do this? Surely Biden and Sanders can hold at least that much of their bases. But so can a candidate like Pete Buttigieg, who makes a powerful generational pitch and can probably count on a solid bloc of pro-gay-rights voters and donors — a not insignificant group in Democratic primaries.

I’d guess Elizabeth Warren can get to 15 or 20 percent around an economic agenda that punishes the wealthy. Cory Booker might be able to do it around a message of healing, and Kamala Harris around pure celebrity. Maybe there’s room for one avowed defender of compassionate capitalism — a John Hickenlooper or Michael Bennet.

But can Kirsten Gillibrand find a bloc of voters who so identify with her feminist rhetoric that they won’t go anywhere else? Can a little-known governor like Jay Inslee build that kind of support around climate change? I’m doubtful.

The point is that this is why the campaigning really matters — all those stops at little diners and speeches in gyms, and especially the coming debates. The question isn’t who’s best known to voters now and can catapult to the top of meaningless polls.

The question is who can build a narrow following that will hang with them, because those will be the candidates who manage to hang around.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: