Why presidential records are quickly becoming the 'dark archives' of America's past

WASHINGTON – White House documents found at the homes of Donald Trump, Mike Pence and Joe Biden barely scratched the surface of problems the National Archives and Records Administration faces in tracking and storing presidential records for posterity.

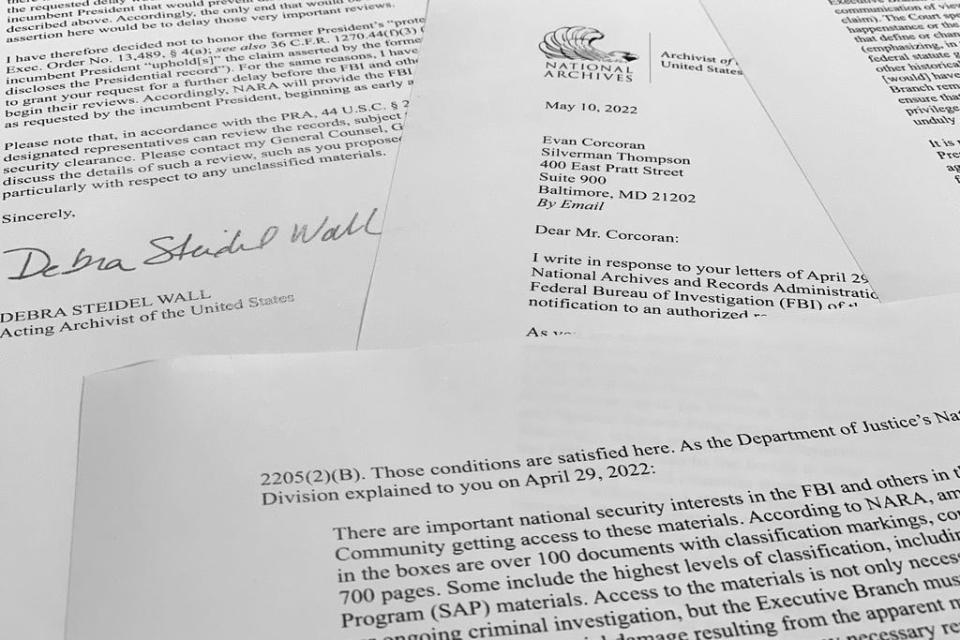

Government officials sometimes cart home documents, in a dispute over what is public and what is personal. FBI agents seized 11,000 documents at Trump's estate Mar-a-Lago beyond the hundreds of classified records.

Thanks to new apps, a growing portion of records disappear as soon as they’re read, like the mission instructions in a spy thriller.

And sorting through the flood of electronic records that become National Archives property under the Presidential Records Act is a massive challenge.

The documents flowing into the archives have grown exponentially over the years. Paper records peaked under the Clinton administration, but the volume of electronic records exploded from 4 terabytes at that time to 250 terabytes under the Trump administration. Each terabyte holds about 500 hours worth of movies, 17,000 hours of music or nearly 86 million pages of documents, according to Kelly Brown, an IT professional at the University of Oregon.

The flood hasn't crested. A White House directive, which has already been postponed a couple of times in the last decade, aims to preserve all federal records in electronic form by June 2024.

The threat is that as documents become inaccessible, it will create blind spots in tracking what an administration did and why. Because of the volume, a significant portion of presidential records remain hidden in plain sight as the National Archives copes with a stagnant budget and the challenges of rapidly evolving technology.

Email records and attachments are piling up so fast, the National Archives can review only a sliver of them for public access – an estimated 0.1% in the past 40 years, according to Jason R. Baron, a professor at the University of Maryland and a former director of litigation at NARA.

“The rest are what I call dark archives,” Baron said. “The problem is that the numbers are only increasing.”

Presidential records 'increasing exponentially.' The budget is not.

Despite the enormous growth in public records, funding for the National Archives budget has remained relatively flat for the past 30 years, according to experts and agency reports.

The agency received 10,645 cubic feet of paper from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s unprecedented four terms. Bill Clinton’s two-term administration generated the most paper records, with 33,196 cubic feet totaling 76.8 million pages.

But that’s when the balance tipped from paper to digital archives. At the dawn of email, administrations for Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush each had 20 gigabytes of electronic records – less memory than a phone now holds.

Graphics: Graphics: How Biden's case differs from Trump's classified documents seized at Mar-a-Lago

The figures grew to 4 terabytes from the Clinton administration, 80 terabytes from the George W. Bush administration and 250 terabytes each from the administrations Barack Obama and Donald Trump. The Trump administration accumulated its records in only one term.

Against that backdrop, the agency's funding for operating expenses totaled $373.3 million in 2012 and $388.3 million last year, according to annual reports. For comparison, President Joe Biden’s proposed budget this year for the Justice Department is $39.7 billion, or about 100 times more than the National Archives, while spending this year on just the juvenile justice system cost about $400 million.

“It’s a tiny agency, frankly with no clout,” Anne Weismann, chief counsel for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington and the Project on Government Oversight, told USA TODAY. “We find ourselves in a position where the number of records of a president is increasing exponentially, especially with email. Yet the resources aren’t, both in terms of money and staff.”

'Nixon could only have dreamed' of apps that erase messages

Congress passed the Presidential Records Act after the abuses of the Nixon administration during Watergate. But a federal judge said in a recent case Nixon could only have dreamed about how apps have made it easier to destroy records.

Apps such as WhatsApp, Wickr, Signal and Confide erase messages after the recipient reads them.

“Richard Nixon could only have dreamed of the technology at issue in this case: message-deleting apps that guarantee confidentiality by encrypting messages and then erasing them forever once read by the recipients,” a D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals panel noted.

After reports early in the Trump administration that top officials were using the apps, the advocacy group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington filed a lawsuit to halt the practice.

“The use of automatically-disappearing text messages to conduct White House business would almost certainly run afoul of the Presidential Records Act,” U.S. District Judge Christopher Cooper wrote in March 2018.

But Cooper refused to order the administration to halt the use of the apps because the Trump administration pledged to preserve its records. A February 2017 memo from the White House counsel’s office reminded staffers to “conduct all work-related communications” on official email and that use of messaging apps such as Snapchat, Confide, Slack and others “is not permitted.”

The appeals court ruled that CREW failed to prove the administration was defying the law.

The strategy to keep things out of the public record is nothing new. Under the Bush and Obama administrations, White House aides scheduled meetings at nearby coffee shops to avoid creating records. The court decisions left watchdogs wondering how much is systematically being lost.

“It’s a huge concern,” Weismann said.

Shift from paper to electronic records left documents harder to search

The technology for storing and transferring the records has changed dramatically in the last 40 years.

When former Bill Clinton left the White House, eight C-5 flights carried 67,000 cubic feet of records totaling an estimated 835 tons to Little Rock.

When George H.W. Bush sent his records to Texas A&M University, local law enforcement guarded a truck convoy at 4 a.m. carting the records to a converted bowling alley for storage until his presidential library was built.

But email – and attachments – emerged under Reagan and exploded from then on. An estimated 600 million emails have been preserved under the Presidential Records Act, totaling the equivalent of 1 billion to 3 billion pages, according to Baron.

The proliferation of records made it difficult for NARA to review each document to remove personal information such as Social Security numbers from records before they are made accessible to the public. The result is only a small fraction of administration emails are publicly available.

Two exceptions that forced the release of emails: lawsuits and congressional requests for documents about Supreme Court nominees.

Three key lawsuits dealt with the Iran Contra scandal under Reagan, the tobacco case U.S. v. Philip Morris and a criminal conspiracy case.

The congressional requests covered documents dealing with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Elana Kagan and Brett Kavanaugh, from when they each worked at the White House.

Absent a staff review, NARA policy is to release documents after 75 years to protect the privacy of people involved.

"But many of these records contain some of the most candid conversations of high-level officials that make up the meat of history," Baron added. "Don’t we want to know sooner than in 75 years what people in the Obama White House said to each other?”

Artificial intelligence technology could help make electronic records more accessible

Baron believes that new forms of artificial intelligence tools may greatly help process records and make them publicly available faster.

Cost estimates for the technology to be used by an agency such as the National Archives would range in the hundreds of thousands of dollars – less than the price of a military helicopter – and could unlock the records for researchers and the public, he said.

"The same tools and techniques can be applied to searching and filtering government records," Baron said.

'Niagara Falls'

The National Archives has begun preparing for the continuing flood of electronic messages, but it’s a daunting task.

Congress began providing additional funding two decades ago under a program called Electronic Records Archives, which grew from $9.9 million in 2002 to $94 million a decade later, before becoming part of the agency’s overall operating funds.

Leslie Johnston, director of digital preservation, said in a statement the National Archives developed expertise in preserving a large variety of electronic records after it began accepting records that were born digitally in 1971. In 2014, the National Archives updated its guidance to federal agencies about the preferred and acceptable file formats for long-term preservation, she said. By 2019, the agency published a Digital Preservation Framework outlining its approaches to preserving nearly 700 types of files, a plan that is updated quarterly, Johnson said.

Laurence Brewer, chief records officer for the National Archives, said in a statement a key part of the agency's ability to preserve the increasing volume of records is the Electronic Records Archives 2.0 system. The system, which is now being tested, is a secure, cloud-based system federal agencies developed to preserve the ever-increasing volume of electronic records, he said.

"NARA is focused on issuing updated guidance, new regulations, and additional oversight and reporting to facilitate and support this mission-critical function," Brewer said.

While the National Archives prepared to handle the wide variety and volume of electronic records, the government has edged toward preserving all of its records electronically.

In August 2012, Jeffrey Zients, the current White House chief of staff who was then acting director of the Office of Management and Budget, directed all federal agencies preserve all permanent records in an electronic format by the end of 2019.

The deadline slipped. In June 2019, OMB acting Director Russell Vought set a new deadline of the end of 2022.

On Dec. 23, 2022, OMB Director Shalanda Young moved the deadline to June 30, 2024.

Whenever the change happens, the government will produce even more electronic records.

“Then expect a flood after that – Niagara Falls – within five to 10 years, consisting of potentially hundreds of millions if not billions of electronic records,” Baron said. “The question is: Is NARA ready for it?”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: National Archives struggles to maintain flood of presidential records

Solve the daily Crossword