Who will be the next governor of California? And why it matters to the rest of the country

LOS ANGELES — It’s a midterm election year — the first of perhaps the most polarizing presidency in half a century. Control of Congress hangs in the balance. The House is likely to flip from Republicans to Democrats; the Senate may too. There are pivotal primaries coming up in Arizona, Virginia, Illinois, Maryland, Indiana, and West Virginia. And there are still House special elections in Ohio and Texas to obsess over in the months ahead.

So why should anyone in the rest of the country care what happens in the California governor’s race?

On paper, the case isn’t particularly obvious. Even in California, few voters seem to be paying attention, and the state is such an outlier in so many ways that it can be a stretch to draw political parallels between what happens here and what happens … well, anywhere else.

But dig a little deeper and it’s clear that the race to succeed four-term Gov. Jerry Brown has major implications for the rest of America.

Three major implications, to be exact.

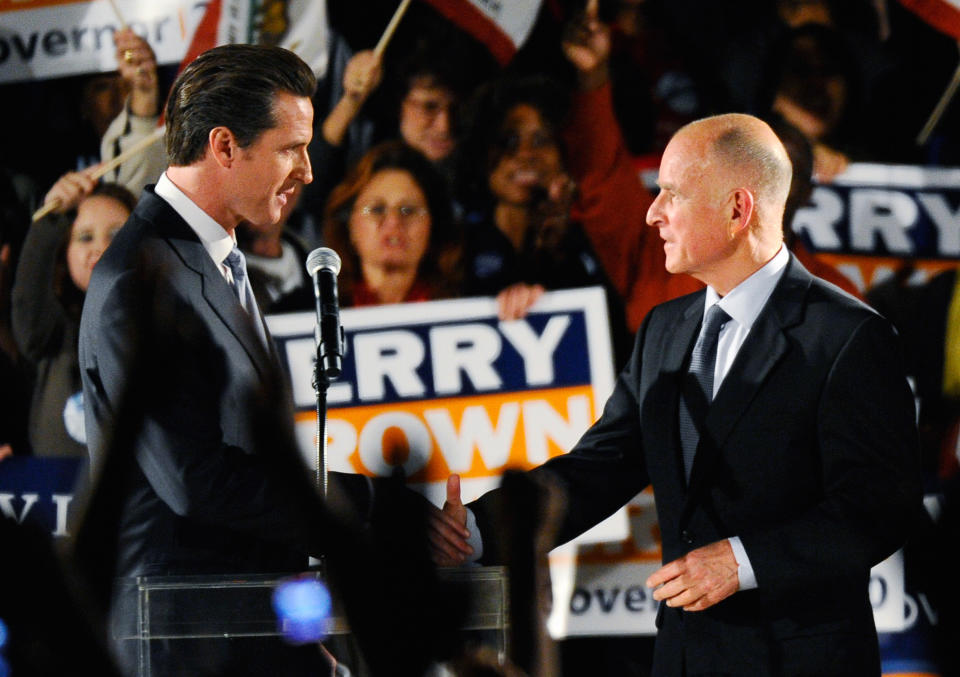

Let’s begin with the backstory. In early 2009, as once and future Gov. Brown was preparing a comeback campaign for the office he’d left 26 years earlier, Gavin Newsom, then the 41-year-old mayor of San Francisco, announced that he would be challenging him in the Democratic primary. Newsom never caught on; polls routinely showed him trailing by 20 points or more. A few months later, in the fall of 2009, he decided to drop out, and the following February, he filed to run for the largely powerless position of lieutenant governor. He won in November and has been serving as Brown’s No. 2 ever since.

But Newsom still wanted the top job. In fact, he wanted it so badly that in February 2015, a mere three months after securing a second term as second in command, he made his intentions known by launching a 2018 gubernatorial fundraising committee. “I cannot recall a candidate ever declaring this early,” Larry Gerston, a political science professor emeritus at San Jose State University, said at the time. The election was still 1,364 days away.

Extreme as it was, Newsom’s early-bird strategy seems to have worked. He’s led every single public poll released since last summer, often by double-digit margins; he’s also reported to have $17.9 million cash on hand, more than twice as much as his nearest competitor. Unless something changes, Newsom, now 50, is a near-lock to place first or second in the June 5 primary and proceed to the general election.

The question is who will go with him. All primaries in California are open and nonpartisan, meaning the top two finishers, regardless of party affiliation, continue on and compete in November. At first, former state Assembly speaker and Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, 65, seemed like the other favorite to advance. The thinking was that Villaraigosa’s potent base — more Latino and Southern Californian than Newsom’s — would propel him past whichever candidate California’s shrinking Republican Party eventually put forward.

Unfortunately for Villaraigosa, that’s not how things have been playing out. Two single-digit Democratic hopefuls (State Treasurer John Chiang, who boasts more money than Villaraigosa, and former state schools chief Delaine Eastin) have been splitting the party’s non-Newsom vote and, as a result, two Republicans (millionaire businessman John Cox and state Assemblyman Travis Allen) have been inching ahead of Villaraigosa in the latest polls.

None of which is to say the race is settled — far from it. California is so big and so expensive that statewide campaigns don’t really ramp up until about a month before voters cast their ballots.

In other words, right now.

During the past week or so, both Newsom and Villaraigosa have released their first television ads. Newsom’s spot, part of a seven-figure buy, claims that he’s been ahead of the Democratic curve on same-sex marriage, gun background checks, and universal health care. Villaraigosa emphasizes his humble beginnings. A charter-school PAC with $7.3 million in the bank — courtesy of donors like Netflix chief Reed Hastings, billionaire philanthropist Eli Broad and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg — has launched a pro-Villaraigosa ad of its own. Cox, meanwhile, has started to barnstorm the state, delivering boxes filled with signatures from voters — 940,000 in all — who want to add a gas-tax repeal measure to the ballot in November. And another independent expenditure group, this one in Cox’s corner, has just debuted a scathing ad that attempts to portray Villaraigosa and Newsom, who both got in trouble in the mid-2000s for having extramarital affairs, as just another pair of #MeToo creeps.

So this is the time to tune in. But why bother if you can’t vote in California?

For starters, what happens in the Golden State’s gubernatorial contest on June 5 could directly affect what happens to the U.S. House in November. In California, at least seven GOP-held House seats are at serious risk of going Democratic; that’s nearly a third of the total that Dems need to flip nationwide to regain control of the chamber. State Republicans fear that if neither Cox nor Allen advance to the general election — if there’s no Republican at the top of the ticket for the first time in California history — rank-and-file GOP voters won’t show up to vote for the party’s imperiled down-ballot candidates. According to the Sacramento Bee, an internal poll conducted by the Cox campaign showed that “barely more half of likely GOP voters in California would turn out” in that scenario.

“The first thing that people see when they open their ballot is the top-of-the-ticket race, and we don’t want Republicans to be discouraged,” GOP strategist Dave Gilliard told the Bee.

“We absolutely need a Republican to get through the primary,” Cynthia Bryant, the executive director of the state GOP said in a statement.

The Republican side of the primary race is important for another reason as well: as a referendum on how blue-state Republicans should run in the Age of Trump. It’s no secret that the president is particularly unpopular in California; he lost here in 2016 by 3 million votes, and a new poll shows that two-thirds of Golden Staters disapprove of his job performance. With headwinds that strong — and a debilitating statewide Republican registration deficit — it would be a shocking upset for either Cox or Allen to beat Newsom in November, assuming one of them even makes it onto the ballot. But both Republicans seem to be seizing on the same two issues as they scrap for second place in the primary: the recent gas-tax increase, which raised prices by 12 cents per gallon, and California’s so-called “sanctuary state” movement, which has seen various jurisdictions push back on Trump’s aggressive immigration agenda by directing state or local police not to assist federal enforcement efforts.

It isn’t hard to see the beginnings of a blue-state GOP playbook here. On the one hand, emphasize simple pocketbook issues that affect as many voters as possible. (“The whole state is paying this tax,” Cox, 62, said Monday, “and the whole state wants it gone.”) On the other, position yourself as a check on the anti-Trump “resistance” that’s gripped much of blue America — and that may be a turnoff for some moderate voters.

“It is absolutely objectionable for people like Gavin Newsom and Jerry Brown to say they are not going to adhere to the federal law on immigration,” Cox recently told the New York Times. “Jerry Brown should not be acting like George Wallace in front of the schoolhouse in Alabama.”

On the issue of Trump himself, Cox is a lot less enthusiastic than Allen. The latter, a 44-year-old former financial advisor from Huntington Beach, echoes the president’s “Make America Great” rhetoric at every turn; the former, a millionaire businessman who lives in Rancho Santa Fe, didn’t even vote for Trump and insists he wants “people to get away from harsh language.” That studied distance from the disrupter in chief, along with his huge cash advantage, is probably why if any Republican advances, it will likely be Cox, who would then be the one to test whether this emerging Trump-era, blue-state GOP strategy can truly compete with its Democratic counterpart.

The task facing Cox’s potential Democratic rivals is defining what that competing vision should be — and that’s the third and final reason why this year’s California gubernatorial race matters beyond California.

Conservatives tend to portray the state as an unbridled liberal fantasyland, and it’s true that Democrats dominate its political system. But that’s a fairly recent development; in 2010, the state’s governor, lieutenant governor, and state treasurer were all Republicans. Meanwhile, even as California Dems have amassed more and more power in subsequent years, including GOP-proof supermajorities in both houses of the state legislature, the party’s ostensible leader, Gov. Brown, has consistently acted as a brake on its most progressive desires.

Once Brown retires to his family ranch in remote Colusa County, however, all bets are off. With an activist base that’s veering leftward in reaction to Trump and legislature that’s largely sympathetic and no longer requires Republican votes to pass laws, a like-minded governor could quickly transform the country’s most populous state into the negative image of Trump’s Washington: that is, a place where policy responses to America’s most pressing problems, from income inequality to education to health care, could actually be implemented. And not just any policy responses — the kind of progressive policy responses that would be pretty much off-limits anywhere else, at a scale that would be impossible to match.

Newsom is the most progressive of the leading Democrats, and the most detailed in his policy prescriptions. His platform includes a number of proposals that national progressives are pushing the party to adopt: a statewide “Medicare for All” single-payer healthcare system; universal preschool; full-service community schools, open every day; a vast expansion of affordable housing, and a state bank dedicated to financing infrastructure projects, small businesses and the growing marijuana industry. He frequently cites his early decision as San Francisco mayor to grant the national’s first official same-sex marriage licenses as evidence that as governor he would have the “courage” to push for trailblazing reforms.

Long considered a fairly moderate figure, Villaraigosa is running as Newsom’s more pragmatic, centrist foil. “Pie in the sky doesn’t put food on the table,” he likes to say of the frontrunner’s single-payer plan, which would require an unlikely waiver from the Trump a.dministration. “It’s snake oil.” On education, Villaraigosa is advocating for more charter schools (hence the independent expenditures) and stricter rules for teacher tenure; as mayor of L.A., he tried to seize control of the city’s public schools, arguing a dramatic overhaul was needed.

“Antonio sees himself as a progressive, but it can’t be just a slogan or a litmus test,” Eric Jaye, a consultant for Villaraigosa, recently told the San Francisco Chronicle. “It has to be about progress.”

The choice for Democratic primary voters, then — and perhaps the broader California electorate, come November — is how far to the left they want the state to go. As far as it’s gone in the past? Or further? As it happens, this is the same choice confronting national Democrats as they struggle to respond to Trump. In that sense, California’s gubernatorial contest could foreshadow the risks ahead for the party, and the possible rewards. For now, the debate among Washington Democrats is just rhetoric. In California, it could actually become reality.

Read more from Yahoo News:

As House wraps up Russia inquiry, top Dem on Senate probe says there’s no end in sight

After relief debacle, Puerto Rico’s governor looks for political revenge in Florida

After a week of diplomacy, an Iran deal still seems out of reach

What Mueller’s questions for Trump reveal about the investigation

Photos: A look back at the work of Shah Marai, AFP photojournalist killed in Kabul