What are we willing to do about low-performing schools in Milwaukee Public Schools and beyond? Right now there's no real plan for change

The most striking thing about Milwaukee’s James Madison High School doesn’t involve the students inside the building.

The most striking thing is the students who aren’t inside.

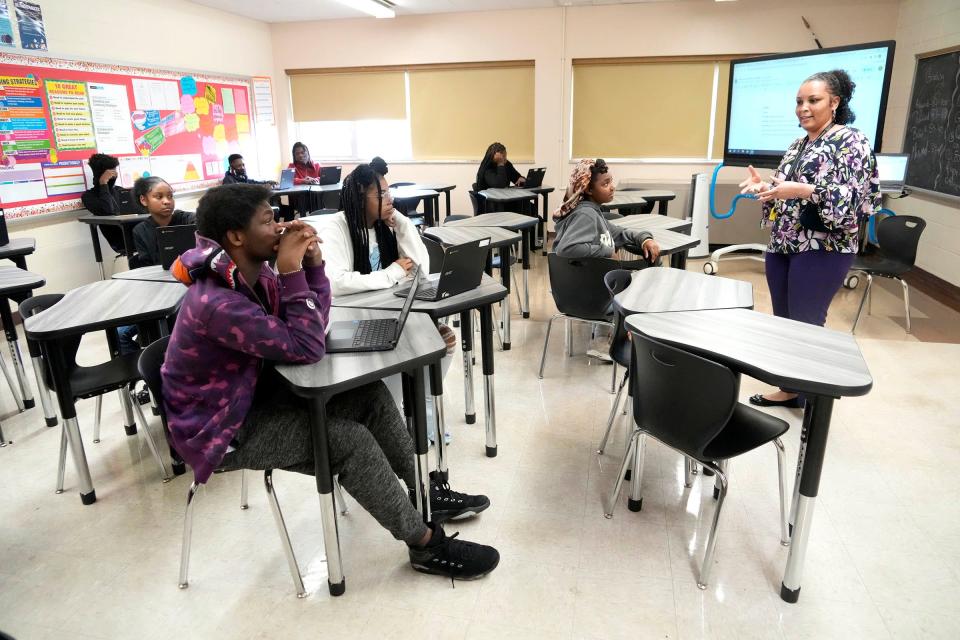

Oh, there’s plenty of reason to take seriously the situation of the students inside. But a recent visit to the northwest side Milwaukee Public Schools building at 8135 W. Florist Ave. showed there were serious efforts to help those students. Teachers and staff were doing pretty much what they were supposed to be doing. School officials say the teaching staff is in reasonably good shape. Classes were proceeding pretty much by the book. The hallways were orderly.

The visit to Madison High is important because it offered a look into big problems facing many schools, in Milwaukee and nationwide, where large numbers of students are on paths to limited success — or no real success — in getting an education. There are things going on inside Madison that deserve appreciation. But, overall, Madison is an example of issues in education that get too little attention or draw resigned responses because solutions are so hard.

Let’s start with how quiet it was inside the school. One reason was that there were so few students present.

Consider a ninth-grade English class on this particular morning. There were 25 desks in the room — but just nine students. At least the nine were there. An administrator confirmed the class roster is actually about 25.

The teacher, Zulica Spencer, is from Jamaica, one of many teachers from outside the United States who were recruited by MPS because of teacher shortages. She was prodding students to talk about a short story. Several of the nine were at least somewhat engaged. Several were not.

Next we visited a ninth-grade class that introduces students to career-oriented programs offered at the school. There were 12 students present and about twice as many desks. The teacher, Justin McMurtry, known as Mr. Mac, talked to students about handling money and things they will need to consider when they get paychecks. He introduced a guest speaker, an events manager at a downtown Milwaukee hotel who offered advice on careers, particularly in the hospitality industry.

As we observed the class, the school’s principal, Alonzo Fuller, said he wants students to learn about real experiences and opportunities. “The goal is to build them up and make them strong in class,” said Fuller, who is in his 29th year in MPS, his 15th year at Madison High and second year as principal. “We try to enrich their lives and make sure they have a bright future in front of them.”

Exposing students to the working world

We also visited the school’s lab, where students are trained to become certified nursing assistants. The program is run in conjunction with the Milwaukee Area Technical College; across a semester, it can serve 10 students. During our visit, two were practicing with manikins the kinds of things a CNA would do for patients in a hospital or care facility. “There’s a waiting list for the program,” Fuller said.

The most active of the classes we visited was in the culinary lab, where 14 students were making pancakes, eating pancakes, doing some textbook work (and socializing). Madison High has emphasized culinary career preparation in recent years. Fuller said the school offers two levels of culinary classes, with six classes and up to 25 students in each class.

Fuller said Madison High offers career-oriented programs from the National Academy Foundation, a private nonprofit based in New York. The school has three NAF academies, focused on health science, finance and hospitality. He said more than 300 students are enrolled in the academies.

“We have a great school; we have great students,” said Lisa Byrd, an assistant principal. “We’re trying to expose them to the working world so they have better choices.”

Improvements are being made every year, aimed at helping students and getting better overall results, she said.

Chronic absenteeism is a problem, as is declining enrollment

Is anything being done about attendance? Several school leaders said individual phone calls are made by an attendance secretary. There are automated phone calls to the homes of students who aren’t in school on a given day. A parent coordinator tries to engage and encourage parents to connect themselves and their children with the school. Every student receives a personal phone call from a teacher at least once a month.

But the number of students in each class stands out. As of the day of this visit, daily attendance at Madison was at 58.6% so far this school year, said Melanie Stewart, director of research, data and assessment for MPS. That’s up slightly from last year. The recently released state report card for the school shows that more than 80% of students have been labeled chronically absent in recent years.

The empty desks speak loudly. Attendance has been a big issue in many urban high schools nationwide for years, and the problem has increased in the aftermath of the pandemic. Wisconsin Public Radio reported on Nov. 21 that nearly 1,000 students enrolled in MPS schools had not attended a single day of school this year. That’s about 1.5% of all MPS students.

Enrollment is also an issue for Madison High. For many years, enrollment was over 1,000. In 2014-15, it fell to 892 students, according to Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction records. It’s been lower than that every year since. As of Nov. 15, enrollment was 625, Stewart said.

Combine the enrollment and attendance figures, and you get a large building with a lot of elbow room.

Student turnover is another concern. Fuller said it was a positive sign that the school enrolled 273 new students this year. However, total enrollment changed little, which points to more than 40% of the students being new to the school this year.

The enrollment follows a pattern that has been common in many MPS high schools for years: Ninth grade is the largest class. Enrollment goes down in each succeeding grade. Specifically, as of one recent day, there were 224 ninth-graders, 180 10th-graders, 134 11th-graders, and 86 12-graders. But that requires some detail: Of the 224 ninth-graders, 130 were “first year” freshmen, and 94 were doing ninth grade for at least the second year. Not earning enough credits to make it out of ninth grade is a long-time MPS issue, which led one administrator years ago to use the term “the ninth-grade parking lot.”

Another major focus of attention within the school: At 26.7%, the percentage of students with special education needs is high.

The state report card for Madison HS says that, as of 2021-22, the graduation rate within up to seven years of starting ninth grade was 72.1%, compared to a state average of 91.8%.

Madison High School principal says the school is safe

This visit indicated that it is generally safe inside Madison High. “It’s a very safe environment, a rich environment,” Fuller said. He said the school's involvement in the Milwaukee Violence Free Zone, an initiative of the nonprofit Greater Milwaukee Foundation, helps.

The school is part of the MPS “community schools” program, led by the United Way of Greater Milwaukee and Waukesha County, which aims to provide services to students and families and help with issues in people’s lives.

More directly when it comes to safety, security aides were at the entrance and many of the hallway intersections in the school. Metal detectors check students for weapons as they arrive. During our visit, we saw no “hall walkers,” students wandering around during class time.

You wouldn’t get that impression of safety from an incident in mid-October when social media postings claimed there were fights involving guns underway in the school. In short order, more than two dozen police squads were parked outside, several TV crews were waiting near the entrance, and a TV helicopter circled overhead. School leaders say the incident was overblown: There were no guns and no injuries. Four people were arrested.

As for fights in the school, Fuller said, “We get ahead of fights.”

Low academic performance — at Madison, but also at other large urban schools nationwide

Academically, student performance, gauged by Wisconsin’s statewide tests, is very low. In spring 2023, in reading and language arts, 2% of Madison High ninth- and 10th-graders were rated proficient or advanced, 13% basic and 35% below basic, while 50% didn’t take the test. In math, fewer than 1% were rated proficient or advanced, 12% basic and 39% below basic, with 49% not taking the test.

That said, the percentages of students who showed at least basic performance in reading and math was higher than in the prior two school years, which is a key to how the school earned a two-star rating on its state report card. The DPI lists two stars as meaning the school “meets few expectations.” A year ago, Madison High got a one-star report card, carrying the label “fails to meet expectations.”

What would it take to improve students’ proficiency in core subjects? Fuller said, “We meet kids where they are, and we build from there.”

Byrd said the school sets “smart goals” for students. You can’t go from A to Z in one step, she said, so they aim for progress and engagement.

Madison High does not stand alone in Milwaukee. State report card scores are not the end-all of judging a school. But the scores offer one gauge of how a school is functioning.

By that measure, three large MPS high schools (Obama, Washington and the Wisconsin Conservatory of Lifelong Learning) had lower overall scores than Madison, and scores were only a few points higher for five other large high schools (Marshall, Pulaski, South Division, Bay View and Hamilton). Test scores were low to very low in all of them; attendance and general student engagement is a problem in all.

Nationwide, much of what is found at Madison High is found at many large urban high schools serving children from low-income homes, and the students are disproportionately Black and Hispanic. (The student body at Madison High is 89% Black and 1.5% white, with small percentages of several other groups.)

Madison can be looked at as a case study in a broad problem. A long list of efforts — federal, state, local, private-sector — have brought little change and little improvement in these high schools, going back more than 25 years. More broadly, studies have concluded that climbing the economic ladder in America has gotten harder in recent times, and young people such as those at Madison High are generally on their way to making a living in lower income brackets.

The paths being offered to the students within the school and in similar schools can lead to stable jobs; CNAs, food service workers, hotel workers are in demand. But these jobs simply don’t pay much.

If what is being done at Madison is by the book, this is not the book being used in a lot of high schools serving students from higher places on the economic ladder or schools where students generally have grander life ambitions.

Issues at Madison reflect more than just what's going on at school

The roots of the issues being faced in a school such as Madison are by no means confined to things going on inside the school walls. They reflect things that have gone on in the lives of students going back to early childhood, and, in many cases, going back for generations. And they reflect things that went on during the elementary and middle school years of all of the children now enrolled in schools such as Madison.

In short, there is a lot of history, much of it not conducive to good school outcomes, behind students inside Madison — and, even more so, behind all of the empty desks on a typical day.

So what could or should be done about the state of Madison High and similar schools? On every level, no real plan for change is being pursued.

The era of big initiatives such as the No Child Left Behind federal law signed in 2002 has waned. Few can even name the current federal education law, which amounted to a substantial retreat from the whole subject. (It is called, one could argue cynically, the Every Student Succeeds Act.) There is no particular sense of urgency around changing the prospects of students in schools such as Madison High.

A visit to the school finds some positive signs amid the multiple problems. There are students who doing their best. There are staff members who are dedicated, hard-working and willing to take on the challenges.

But is that enough for a bright future for most of these teens? And what are we — the big “we” — willing to do about it?

Alan J. Borsuk is senior fellow in law and public policy at Marquette Law School. Reach him at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: No apparent plan to help improve low-performing MPS schools