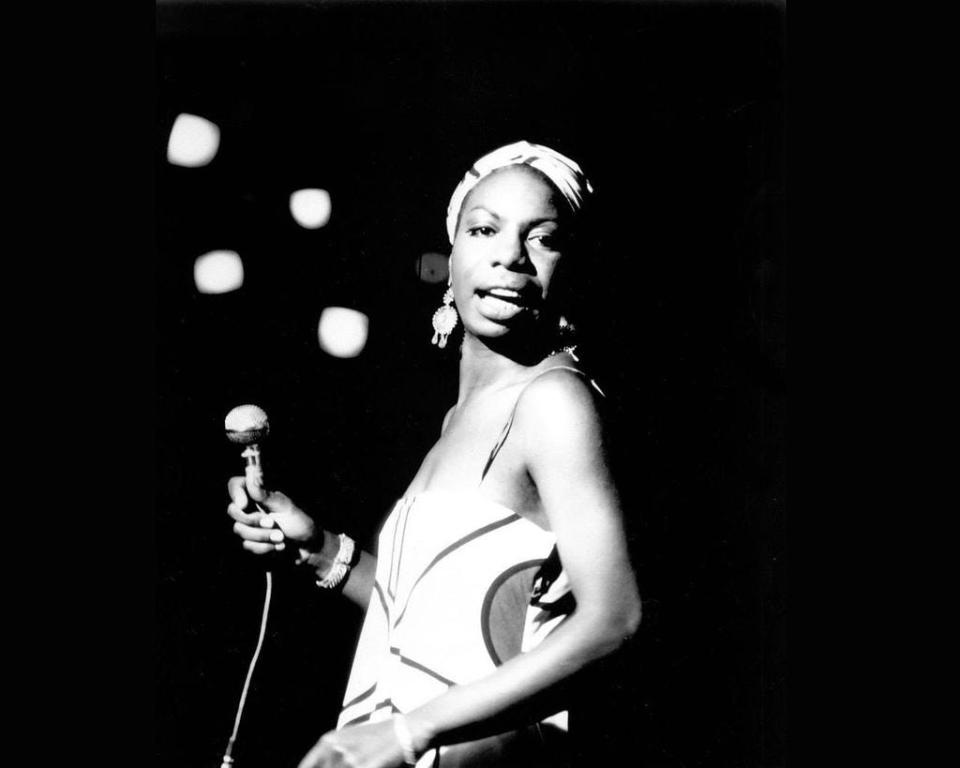

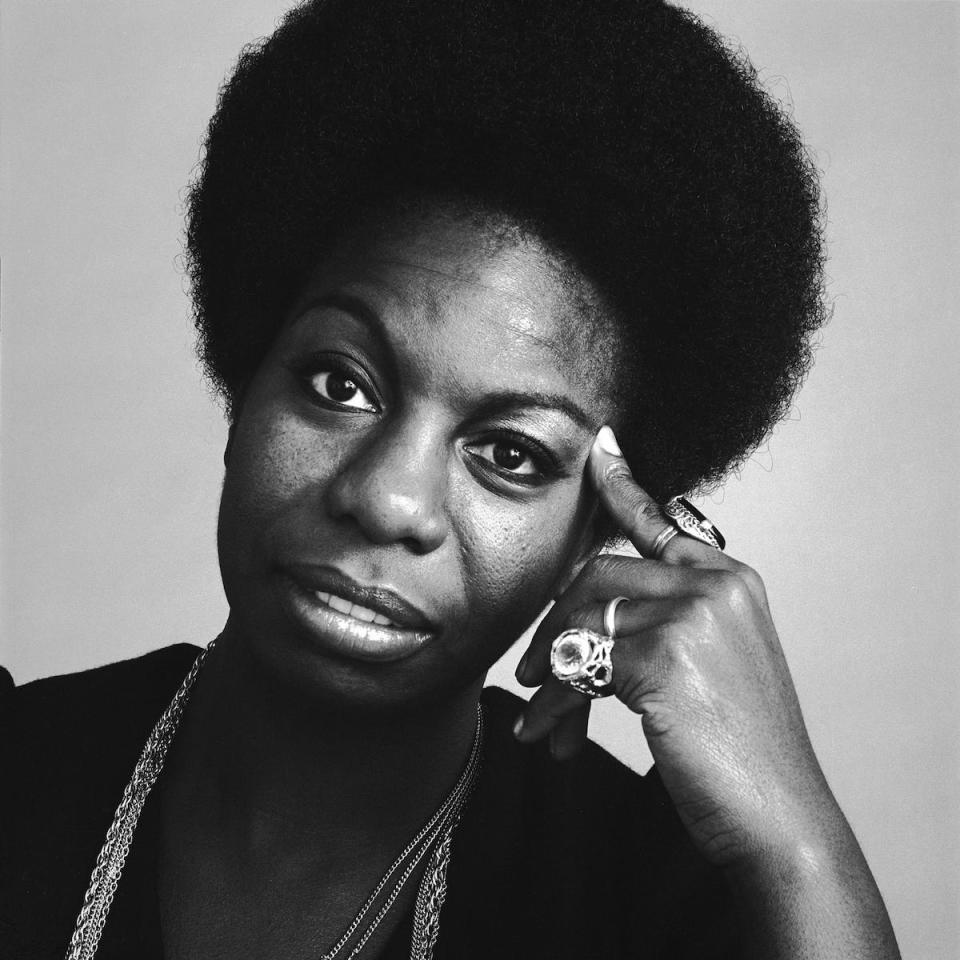

WNC History: Nina Simone's musical talent apparent while growing up in Western NC

Before the American public knew her as Nina Simone “the high priestess of soul,” Eunice Kathleen Waymon was already making a name for herself in Western North Carolina. Born in 1933 at 30 East Livingston Street in Tryon, Eunice’s musical talent was apparent almost immediately.

“When she was eight months old, my daughter hummed ‘Down by the Riverside’ and ‘Jesus Loves Me,’” Eunice’s mother, Mary Kate Waymon, a Methodist minister, remembered. At 2 1/2, Eunice was playing “God Be with You till We Meet Again” on the pump organ in her home.

She came by her talents honestly — her father played guitar, banjo, and harmonica, and sang in a quartet. Her mother sang and played both organ and piano.

Though Eunice’s father, John Divine, had run successful businesses in Tryon, the Depression and an illness that nearly killed him hit the family’s finances hard. By the time Eunice turned 5, the family had moved from E. Livingston Street into a smaller house, and her mother had taken a position as a housekeeper for Tryon resident Katherine Miller.

Nurturing talent

Though the Waymon family’s finances were suffering, her mother’s new housekeeping job became a boon for Eunice. After seeing Eunice play — likely with her sisters Dorothy and Lucille as the Waymon Sisters, Kathleen Miller offered to pay for Muriel Harrington Mazzanovich to give Eunice piano lessons, with the promise that if Eunice did well, they would find a way for her to continue her musical education. Eunice played Bach at her first lesson, and a year later, Mazzanovich started the Eunice Waymon Fund to raise money to guarantee her “secure musical future.”

By the time she was 6 years old, Eunice had become a regular pianist at her home church. She often traveled with her mother when Mary Kate served as a visiting preacher. As an adult, she remembered of her mother, “She knew what a sensation her tiny girl caused with congregations that had never seen me play before, and it was a good way of catching people’s attention before she started preaching.”

While training classically with Mazzanovich, Eunice continued attending church services regularly. She later recalled, “Gospel taught me about improvisation, how to shape music in response to an audience and then how to shape the mood of the audience in response to my music.” She also attended Holiness Services because, “the music ... had an incredible rhythm, it sounded like it came straight out of Africa, and I took to going … every week just to get that beat.”

People all around Tryon had begun to talk about the child prodigy. “Every church took up a collection for the (Eunice Waymon) fund, the paper started an appeal and the council collected on my behalf,” Simone wrote in her 1991 autobiography, “I Put a Spell on You.” In exchange, Eunice pledged to play regular recitals.

Early activism

It was around 1944, during one of these recitals, that Eunice first saw a chance to use her musical gift to fight for civil rights and social justice. She wrote in her autobiography: “When I was 11 years old, I was asked to give a recital in the town hall. I sat at the piano with my trained elegance while a white man introduced me, and when I looked up, my parents, who were dressed in their best, were being thrown out of their front row seats in favor of a white family I had never seen before. And Daddy and Momma were allowing themselves to be moved.”

More: WNC History: 'Moms' Mabley, from Brevard to Asheville to national prominence on the stage

More: WNC History: Bettie Sims was not a typical moonshiner

Though John Divine and Mary Kate Waymon had been invited, the public event was billed as whites only. Eunice spoke up. She remembered, “Nobody else said anything, but I wasn’t going to see them treated like that, and stood up in my starched dress and said if anyone expected to hear me play then they’d better make sure that my family was sitting right there in the front row where I could see them. ... So they were moved back.”

Simone recounted this incident in numerous interviews as being a turning point in how she understood the world and her place in it as a Black female. In her autobiography she wrote, “All of a sudden it seemed a different world, and nothing was easy anymore. I really had thought that all white people were like Miz Massy (Muriel Mazzanovich) and Mrs. (Katherine) Miller, all kind and elegant, all polite. I had no reason to think otherwise: they were the only white people I had ever talked to for any length of time. But now prejudice had been made real for me and it was like switching on a light.”

As Tryon developed in the early 20th century, the town — like those across the South — was segregated along racial lines. However, though schools, churches, and businesses were separate, they were often in close proximity to each other. Both white and Black businesses operated on Tryon’s main street, Trade Street, and both white and Black households were scattered throughout the town. Simone’s biographer, Nadine Cohodas, wrote of Tryon, “the two races lived near each other in checkerboard clusters, an arrangement that fostered, depending on one’s viewpoint, an inchoate integration or imperfect segregation.”

Eunice’s early confidence to push back against discrimination may have been influenced by other members of Tryon’s Black community. In one widely publicized incident, Leroy Wells, the principal of Eunice’s school, who for years had asked for funding for repairs and maintenance, paid two men to burn down the deteriorating school building, “so that they could have a nice brick building like the other schools.” Though Wells served prison time, his plan worked; the Tryon Colored School, in ashes, was rebuilt as the brick Edmund Embury School.

In the following years, contributions paid to The Eunice Waymon Fund were used to finance Eunice’s continuing education. She recalled, “Miz Mazzy wanted me to have the best music tuition possible, Momma wanted me to receive the social training a black pioneer would need in order not to let down her race, and Mrs. Miller wanted me to have a normal life that offered a chance of personal happiness. The answer they decided on was fifty miles from Tryon in Asheville: the Allen High School for girls.”

Move to Asheville

Asheville’s elite Allen School attracted young Black women from across the United States as well as from many counties in western North Carolina, where public education for Black girls and young women was often either inadequate or non-existent. A number of other women who would become famous or accomplished in their fields attended Allen throughout the years — including Christine Mann Darden, a NASA mathematician who was featured in the 2016 book "Hidden Figures."

(The former Allen School building is now home to Explore Asheville, the city’s tourism department. In October 2023, the school’s state-wide significance was recognized with an N.C. historic highway marker.)

Eunice began boarding at Allen in 1947 and continued studying piano, but quickly outgrew the school’s program. Mazzanovich arranged for her to take lessons with Grace Carroll, an internationally-recognized pianist. Notably, Grace and her husband, Dr. Robert S. Carroll, lived adjacent to Highland Hospital — a sanatorium and mental hospital in the Montford area that Dr. Carroll had started in 1904. In 1948, the year after Eunice arrived in Asheville, author Zelda Fitzgerald died in a fire at the hospital. Whether Eunice ever crossed paths with Zelda, who was well-known at the time of her death, is currently unknown.

While at Allen, Eunice also took classes from Clemens Sandresky, a Harvard-educated musician and teacher. Sandresky hosted Eunice’s Asheville debut piano recital at his home during the spring of 1948. According to Sandresky, the recital was “crowded with distinguished members of the community, classical-music buffs and most of (his) friends,” but Eunice’s friends “sat on the porch outside and listened through an open window.” One of the guests told Sandresky that “the evening was a first for Asheville … not because Miss Waymon was a budding virtuoso, but because she was black (and) poor.”

Eunice excelled at Allen — she served in student government, drama club, and in the school’s NAACP chapter, even helping to bring Langston Hughes to Asheville for a presentation. After Eunice graduated from Allen as valedictorian in 1950, Sandresky recommended her to The Juilliard School of Music in New York, which he had also attended.

Mazzanovich helped Eunice secure a scholarship for the school’s summer session, and Eunice’s mother used her church connections to find her daughter an apartment close to Juilliard. Eunice traveled back to Asheville throughout the summer to work with both Mazzanovish and Carroll to plan and prepare to audition for the prestigious Curtis Institute in Philadelphia; this would be the next step in achieving her dream of becoming a concert pianist.

In 1951, 69 other students applied alongside Eunice for three openings at Curtis. She later wrote, “when I was rejected by the Curtis Institute it was as if all the promises ever made to me by God, my family, and my community were broken and I had been lied to all my life … and all I could think about was what I had given up over the years to get where I was the day I heard Curtis didn’t want me, which was nowhere.” The rejection stung and even more so when people told her they believed that she was not accepted because of the color of her skin.

More: WNC History: The Revolutionary journeys of 2 young WNC women

More: WNC History: Rumors of Babe Ruth's death after Asheville stop were greatly exaggerated

Popularizing a legacy

Though she continued her studies, she began letting go of her dream to be a professional classical musician and took up teaching. But when she discovered she could make more money playing Atlantic City clubs, she hired an agent, who booked her at the Midtown Lounge in June 1954. Worried that her mother, who had moved with other members of her family to Philadelphia to support Eunice’s career, would disapprove, Eunice gave the venue the name Nina Simone — Nina had been a nickname and Simone the name of a favorite actress (Simone Signoret).

Over the next six years, though she continued quietly planning a return to classical music — perhaps at Julliard — her career in popular music grew. She was picked up by a record label, released albums, and began playing larger venues and performing on television shows.

As her public profile became more recognizable, Simone became a vocal Civil Rights activist, writing, releasing, and performing songs that spoke directly to the movement. She now saw a permanent future for herself beyond the world of classical music. “My music was dedicated to a purpose more important than classical music’s pursuit of excellence,” she wrote in her autobiography. “It was dedicated to the fight for freedom and the historical destiny of my people.”

Simone continued this musical trajectory, one that she had begun as a child in Western North Carolina, until she died at age 70 in 2003.

The Eunice Waymon Birthplace

It was not long after her death that the Waymon family's small three-room E. Livingston Street house in Tryon “where (Eunice) was born and was first introduced to music and learned to play the organ and piano” began to face threats of demolition.

After years of uncertainty, the home which the National Trust for Historic Preservation calls the best surviving “symbol of Simone’s early life and legacy,” seems to have finally been guaranteed protection. In 2017, four African-American artists from New York City purchased the house and began working with the National Trust, the Nina Simone Project, World Monuments Fund, and N.C. African American Heritage Council to “apply their collective artistic vision to reinterpret Simone’s home into something that reflects her dynamic, complex legacy.”

The National Trust named the house a “National Treasure” in 2018, an honor that has been bestowed on only 80 other sites across the United States. In 2020, Preservation North Carolina received a preservation easement on the property, and, in May 2023, the house — now known as the Eunice Waymon Birthplace — was added to the National Register of Historic Places because of “the influence of her experience in Tryon on her later musical career and Civil Rights activism.”

For more information, visit savingplaces.org/places/ninasimone.

Anne Chesky serves as the executive director of the Presbyterian Heritage Center in Montreat. She grew up in Riceville.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: WNC History: Nina Simone's talent apparent while growing up in Tryon