Women speaking out changed 2017. Will it be a permanent shift?

Time magazine dubbed 2017 the year of the silence breakers, as powerful men who misused their power were brought down by the women they’d wronged.

But while it’s true that 47 men have been forced out of prominent positions this calendar year, with another 26 suspended, on leave or under investigation, this cultural comeuppance arguably began the year before, on July 6, 2016. That’s when newly fired Fox News host Gretchen Carlson filed suit against then-Fox News chief Roger Ailes, accusing him of retaliating against her when she refused his sexual demands. At first she was a lone voice, but over the weeks other women came forward with similar stories, and on July 21 of that year, Ailes resigned.

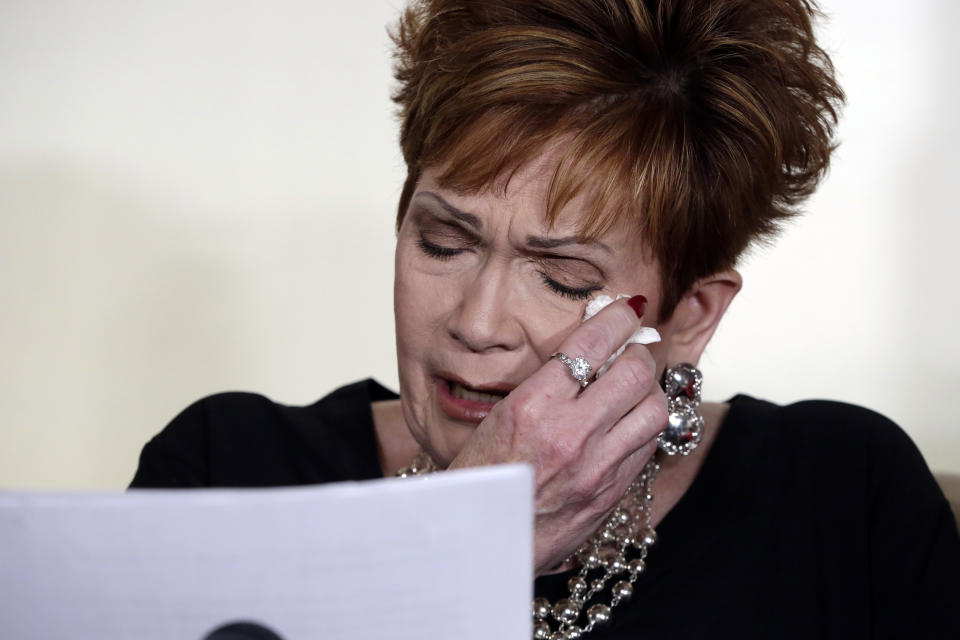

Looking back — and forward — from this vantage point, Carlson recently spoke with Yahoo News about the stunning domino effect of the past few months, why the so-called national reckoning had taken hold at this particular moment, whether the apparent cultural shift was permanent and what the next year might bring.

Carlson herself stresses that credit really belongs to Anita Hill, who testified before Congress in 1991 about how then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her when she was his employee at both the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Hill’s testimony was the first news story Carlson covered as a TV reporter at WRIC-TV in Virginia. It was also “the first national conversation about sexual harassment ever,” Carlson says, and while historic and a good start, the conversation’s impact only went so far. While anger at the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee being condescending to Hill did spur a record number of women to run for Congress and win, it did not keep Thomas off the court. And while it did lead corporate America to create rules about unacceptable behavior in the workplace, many of those rules proved to be ineffective at best and harmful at worst for later generations of women.

“A lot of companies put into effect sexual harassment training and thought the problem was solved — it would just go away,” Carlson says.

In particular, arbitration clauses became common for settling sexual harassment accusations in many workplaces, coupled with nondisclosure agreements barring women from speaking about their allegations as a condition of receiving a settlement. The result, Carlson says, “was a secret chamber of arbitration, which is why we haven’t heard about many of the cases that were settled over the years. It silences women.”

There was such a clause in Carlson’s Fox News contract, saying all lawsuits against the company must be heard by an arbitrator. Carlson’s legal team circumvented that restriction by suing Ailes directly. “That was a strategy my lawyers came up with that happened to work in New York because there was a law on the books that facilitated that. It was not the case in every state.”

At first, Ailes’s allies rallied publicly to his defense. “It was the most excruciating choice of my life and a very lonely experience,” Carlson says. Then five women came forward to New York magazine with stories similar to hers, and eventually the mogul was forced to step down — albeit with a reported $40 million severance package.

In the weeks and months after she came forward, Carlson says, she “heard from women throughout the country — first dozens, then hundreds, then thousands. They were from every socioeconomic level, every line of work. Teachers, police officers, oil rig operators, members of our military, waitresses, assistants, flight attendants.” She keeps listing and listing the professions. “That made me realize this was everywhere.”

“Everywhere” would soon include an “Access Hollywood” bus and an audiotape of a man who would be elected president of the United States — despite the 17 women who went public with sexual misconduct allegations against Donald Trump. On the one hand, Carlson says, Trump’s election in spite of all those allegations felt like a step backward from the progress her lawsuit had promised. On the other, though, she believes that everything that has happened this year was made possible by the anger many women felt last year as they watched an accused sexual predator reach the White House.

Ailes’s resignation “showed it was possible to be believed and to bring down a powerful man,” she says. Trump’s election, on the other hand, “showed that women still are not always believed.”

In that disconnect there was outrage. And many of those who accused Harvey Weinstein of rape, assault and harassment — telling their stories in the New York Times and the New Yorker in October this year — were spurred by that outrage. As Janice Min, former head of the Hollywood Reporter, told Bill Maher just after Weinstein was forced to resign from his company, the “feeding frenzy” over Weinstein was, in her opinion “all just sublimated anger towards Donald Trump.”

So it went through so many of the industries that Carlson had heard from the year before: restaurants, newsrooms, statehouses, fashion, finance, tech. The #MeToo hashtag brought out countless stories from women about their harassment and abuse. Then came another Election Day, Dec. 12, in Alabama, and this time a candidate accused of a history of sexual misconduct with underage girls was not voted into the Senate.

What, then, will happen next year? Was this swelling of voices a permanent change in the definition of what is acceptable behavior between men in power and women who work with them? Or was it just a blip, a noteworthy moment that will be looked back on as an incomplete promise, as was the case with Anita Hill?

Already there are signs of a backlash, an attempt to recast the outpouring of stories as an overreaction, an overreach. Last week, Rupert Murdoch dismissed as “nonsense” the charges that led to the payment of millions in sexual harassment settlements and the resignations of three of his most visible staffers. “That was largely political, because we are conservative,” said Murdoch, whose media empire includes Fox News.

And two days later Matt Damon caused an uproar when he tried to explain that not all harassment is equally bad. “There’s a difference between, you know, patting someone on the butt and rape or child molestation, right?” he said in an interview. Former co-stars quickly pointed out that nothing about #MeToo was equating these things and that to suggest otherwise was to dismiss the ubiquity of misbehavior of all kinds.

“Most men … simply cannot understand what abuse is like on a daily level,” said actress Minnie Driver, a former co-star and former romantic partner of Damon’s.

There is also increasing concern that the problem will be perceived as one of rich and famous men behaving badly, and will be seen as solved when enough such men are replaced. Rebecca Traister, a columnist at New York magazine, wrote of having to do a kind of triage as women contact her daily “ready to finally out their repellent bosses. To many of them I must say that their guy isn’t well-known enough, that the stories are now so plentiful that offenders must meet a certain bar of notoriety, or power, or villainy, before they’re considered newsworthy.”

Carlson also fears that because attention is de facto skewed to offenders in high-profile industries, the victims of less famous men will remain overlooked and powerless. She is somewhat heartened by recent articles such as the one in the Washington Post about harassment in the hospitality industry and in the New York Times about a decades-long pattern at the Ford Motor Company. And she regularly finds herself telling women in less visible fields, “Please go to your local media — in Topeka, in Tuscaloosa. If there ever was a moment when people are interested in telling your story, it would be now.”

But if all these stories are not accompanied by structural and cultural change, she says, the moment will be lost. This is why she is lobbying for passage of a bill just introduced in Congress that would eliminate forced arbitration clauses as a condition of employment. And she is working with the group All in Together to hold three-day workshops around the country for women in blue-collar, hourly-wage professions to train them about ways to fight back against domestic violence and sexual harassment.

She created that program, she says, “because when people first asked me, ‘How do you help the single mom working three jobs who does not have a voice?’ I did not have an answer. Now I hope I do.”

_____

Best of 2017 Yahoo News Features