For those worried about Donald Trump, history offers survival lessons

Since election night, millions of Americans who voted against Donald Trump have been torn by competing impulses. They have heard the words of President Obama the day after Trump’s victory: “We are now all rooting for his success in uniting and leading the country” and “We have to remember that we’re actually all on one team.” They’ve thought of all the noble Americans in our past who found grace and magnanimity in more trying times. Lincoln! Speaking at his inaugural, extending a hand to the seceding Southerners: “We are not enemies, but friends.”

But then they turn on the television and watch commentators talk about the Trump transition as politics as usual. They feel a nagging doubt. They remember how fervently they believed during the campaign that Trump was a threat to the republic. Balancing generosity and vigilance feels impossible. They owe it to the republic to treat this transition as any other, to banish, at least for the time being, the idea that Trump is an American Putin, Mussolini or Hitler. But what if he is?

The history of the presidency does not offer easy comfort — we have simply never had a figure like Donald Trump in the Oval Office before. But consolation is there in the mere fact that the republic has survived 44 presidencies before Trump’s, not all of which were moments of shining glory. Some of our presidents were Trump’s equals as easily provoked hotheads — it’s probably for the best that Andrew Jackson did not have Twitter. Others were his equals in brutish vulgarity — one shudders to imagine what Lyndon Johnson might have said if given a few hours to kill with Billy Bush. Some presidents were simply bad at the job.

And yet we’ve made it through. If we are, in fact, in for a scary four years, previous moments of challenge in the history of the presidency offer lessons in how to survive several different kinds of trouble from President-elect Trump.

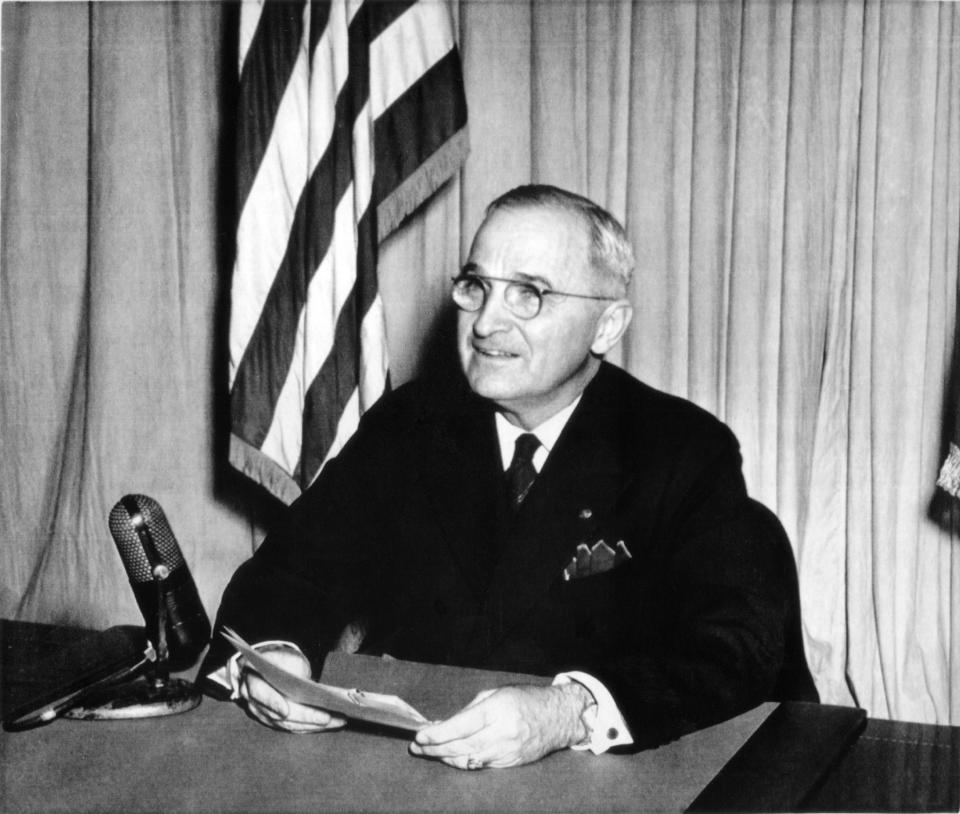

Scenario 1: He’s Truman.

The best hope for a Trump presidency is that the real Donald Trump is a much better person than he appeared to be in the campaign. While believing in this Good Trump requires a considerable suspension of disbelief, assume for a moment that it’s true. Even a goodhearted President Trump would still face a glaring experience deficit. In a moment when the American president faces myriad potential crises at home and abroad, we will soon have a chief executive who has never before held public office or apparently given much thought to many areas of public policy.

But if inexperience is Trump’s only problem, history says we may end up OK. Other presidents have come to the job facing similar experience deficits — and in even more difficult times than our own. In April 1945, Franklin Roosevelt died. His little-known vice president, Harry S. Truman, was thrust into the presidency in a moment of great trial. Americans were still fighting the Second World War in two theaters, scientists were in the late stages of developing an atomic bomb and the Allied powers had charged themselves with designing a new order for the globe. Plucked by FDR from the Senate, Truman had served less than three months as vice president and had virtually no experience in statecraft. His friends, Time magazine reported shortly after he took office, believed “with almost complete unanimity … that he would not be a great president.” Even Truman was struck by the awesome responsibility thrust upon him. “Boys,” he told White House reporters, “if you ever pray, pray for me now.”

Yet Truman endured, and historians have come to marvel over how, despite his inexperience, he was able to intuit postwar geopolitics and invent a new role for America as leader of the free world. Some of our greatest presidents were deemed similarly unprepared for the problems facing the nation at the outset of their terms. A newly elected Abraham Lincoln went to Washington derided as a “third-rate Western lawyer.” The columnist Walter Lippmann, assessing Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, declared him “a pleasant man … without any important qualifications for the office” of president. Meanwhile, sterling credentials have never been a guarantee of presidential success. It would be hard to design better résumés for governing than those of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, yet they still gave us Vietnam and Watergate.

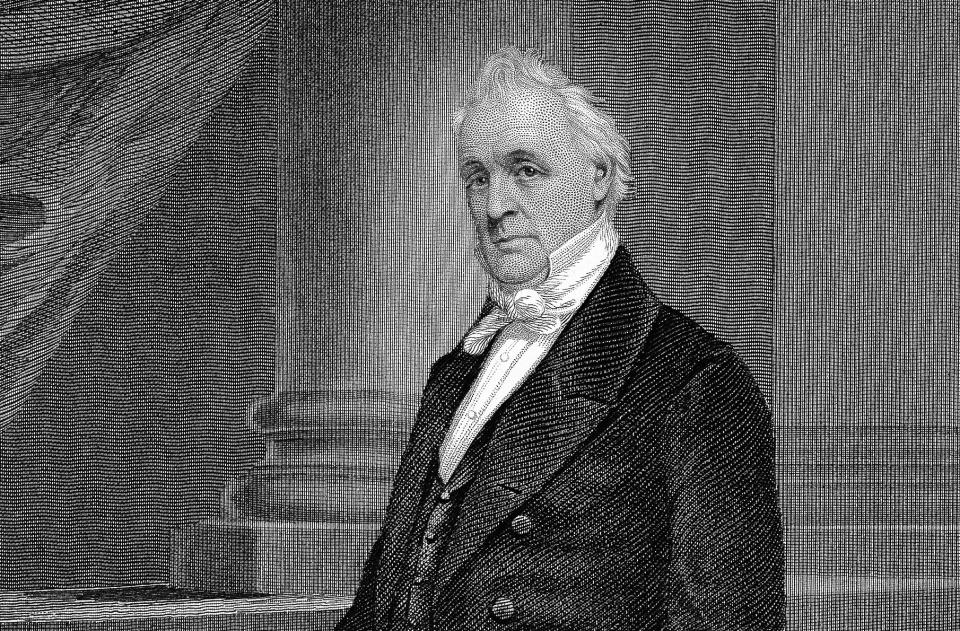

Scenario 2: He’s Buchanan.

But what about the many signs that Trump is not just inexperienced, he’s also incompetent? His multiple bankruptcies and failed businesses, his odd personnel choices, his seat-of-the-pants management style? The best example we have of a well-intentioned but utterly hapless president is James Buchanan, the man who failed to keep the country together as it divided over the issue of slavery. His four years in office were a sad cascade of bad decisions rooted in wishful thinking — that the Supreme Court could resolve the issue of slavery in the Dred Scott case; that secession-minded Southerners could be appeased with concessions and conciliatory talk. On his last day in office, he addressed his successor as they rode back from the inauguration: “If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland” — his Pennsylvania home — “you are a happy man.”

The consolation in the Buchanan example: That successor sitting beside him was Lincoln. Frequently, some of the worst presidents have been followed by some of the best — Buchanan was succeeded by Lincoln, Herbert Hoover by FDR. As a president’s public support falls away, a talented politician sees his chance to fill the vacuum. If Trump is truly in over his head, we will probably know it soon enough and, with good luck, a once-in-a-generation political talent will swoop in to clean up the mess.

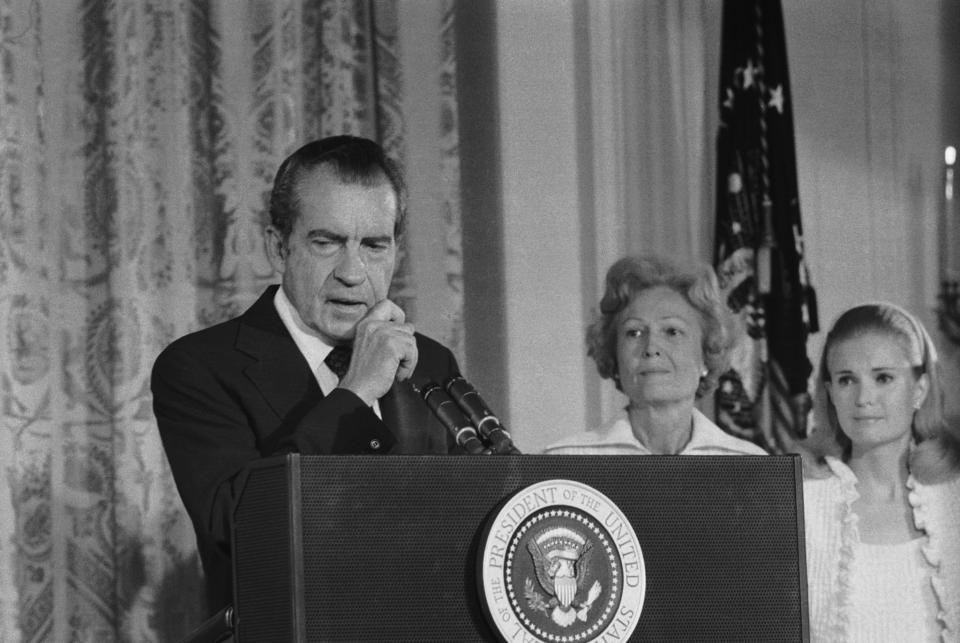

Scenario 3: He’s Nixon.

The more frightening possibilities for a Trump presidency surround his temperament and his authoritarian tendencies. There’s his hostility to the press and to peaceful protest, his threats to jail his opponents, his fondness for strongmen, past and present. For most Americans, Nixon’s presidency is the most vivid example of a presidency run amok, a cautionary tale for what Trump could become. But while the Watergate era showed the dangers of a president who steps outside his constitutional bounds, it also demonstrated how our system can effectively police a president who believes himself above the law. The Congress, the courts and the press all did their part to keep the country intact.

Trump is a more gifted public performer than Nixon and it is possible that he could use his talents to delegitimize the press and the courts in a way that Nixon could not. It’s worth remembering, though, that when the Watergate investigations began, Nixon’s bond with the public was quite strong: in his 1972 reelection he won 49 out of 50 states.

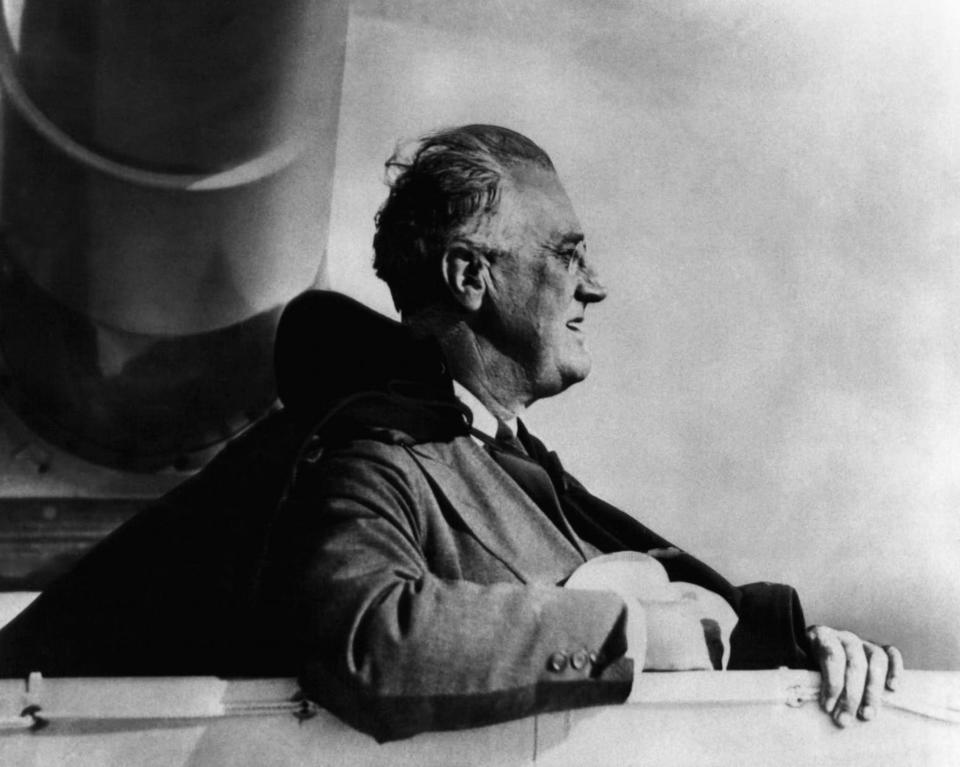

Scenario 4: He’s Adams, Lincoln or FDR.

American history contains an unsettling truth: The list of presidents who violated individual liberties includes some of the most exalted figures in our past. John Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. In the Civil War, Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus. In World War II, FDR ordered the forced relocation of Japanese-Americans into internment camps. With historical distance, we have justifications for their actions — Lincoln had a responsibility to preserve the Union that superseded constitutional constraints; the Japanese internment was a wrong and unjust decision, but one of many choices made by a president who was ultimately responsible for preserving freedom in the world. But viewed in isolation on purely moral grounds, Lincoln’s actions are difficult to defend and FDR’s impossible.

If presidents of the highest character and qualification were tempted to step outside the Constitution in moments of crisis, what’s to stop a President Trump? At present, conventional wisdom is that the unconstitutional ban on Muslim immigration that Trump floated in his campaign has no future — Trump doesn’t talk about it anymore, Congress wouldn’t pass it and, anyway, it’s impossible to administer. But imagine Trump riding a wave of public approval after a spectacular 9/11-style attack, theatrically rallying the country’s spirit, promising Americans he would act. Would a ban on Muslims, or, even worse, a registry of Muslim-American citizens (which at one point in the campaign Trump suggested he favored) seem so impossible then?

The Constitution offers us good remedies for dealing with bad presidents. If Trump appears to a majority of the nation like the second coming of Nixon, or Andrew Johnson or Warren Harding, or any of the other flawed presidents in our past, the republic will be fine. The more dangerous scenario is a popular Trump presented with a national emergency and a public demanding swift action. Given what he has already told us, that is the President Trump we should watch carefully — and fear.

Jonathan Darman is the author of Landslide: LBJ and Ronald Reagan at the Dawn of a New America.