Wounds are still raw in Ferguson, three years after Michael Brown

![Left to right, former Police Chief Tom Jackson, Police Chief Delrish Moss, former Attorney General Eric Holder, Lezley McSpadden, Rev. Tommie Pierson, Sabrina Webb. (Photo illustration: Yahoo News, photos; Michael Thomas for Yahoo News [2], Mark J. Terrill/AP, Jeff Roberson/AP, Michael Thomas for Yahoo News [2]; background photos: Charlie Riedel/AP, David Carson/St Louis Post-Dispatch/ZUMAPRESS.com, Lucas Jackson/Reuters)](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/W64fyxzMl81yfVfkEpUdlA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD03MTE-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/homerun/feed_manager_auto_publish_494/be28190a651a354bf862e5a1597dff08)

FERGUSON, Mo. — Canfield Drive is the kind of winding, tree-lined street that feels safe to walk in the middle of — especially on a hot summer day.

On a recent steamy afternoon, the loudest noise on Canfield came from girls playing in the small field of grass beside one of the several apartment complexes lining the street.

Only the discreet bronze plaque in the sidewalk signifies that this quiet block is where, just before noon on a similarly steamy Saturday in August 2014, a white police officer shot and killed an unarmed black teenager, leaving his bleeding corpse to lie on the hot pavement for four hours.

The plaque bears a copy of the picture that was widely shared in the media, of 18-year-old Michael Brown in his cap and gown on graduation day, and reads in part: “I would like the memory of Michael Brown to be a happy one. He left an afterglow of smiles when he was done.”

In the telling and retelling of the story of Brown, whose last minutes have been analyzed and disputed endlessly (did he have his hands up when he was shot? What happened in the convenience store just before he was stopped?) those four hours have taken on enormous symbolic significance.

To some of Ferguson’s African-American residents, who make up more than two-thirds of the population, the decision to leave Brown’s body in full view of neighbors and passersby, including members of his family, was an indication of how little the black teen’s life mattered to the police.

For others, the open-air crime scene wasn’t just inconsiderate or disrespectful, but motivated by something far more malicious.

“For the police to shoot somebody and leave him laying in the street in the heart of a community, in front of his family and friends and neighbors…to me, that was tantamount to slavery,” said Rev. Tommie Pierson, whose Greater Saint Mark Family Church was a hub for protesters in the days and months after Brown’s death.

“When you punish somebody, you make everybody look.”

As the anniversary approached, Yahoo News went to Ferguson to find out how Brown’s death has changed the city and the people involved in it, and how the case has cast a long shadow over relations between the police and minority communities in cities around the country. Some — like the former police chief, Tom Jackson, who was dismissed in the wake of the case, and former Attorney General Eric Holder, whose department issued a scathing report on the state of criminal justice and race relations in Ferguson — were eager to share their stories. Others, like Police Officer Darren Wilson, who did the shooting, or Brown’s friend Dorian Johnson, who saw it happen and whose provocative account of Brown kneeling on the ground with his hands in the air when he was killed triggered the weeks of protests that followed — refused to talk or couldn’t be located.

Slideshow: Dramatic images from the 2014 Ferguson protests >>>

What we found was a city still traumatized by its turn in the national spotlight, but hopeful that new police leadership will heal its wounds — and a nation that has reluctantly been forced to come to grips with a problem it thought had been resolved a half-century ago.

Pierson is hardly the only person to interpret those first few hours after the shooting as a lynching-style warning to the rest of the community — a fact that still bothers Jackson.

“What a horrible thing to say,” said Jackson. “I mean, what a horrible thing to think. … It’s outrageous.” Jackson says that while he now regrets leaving the body outside for so long, the delay was because the county’s crime scene investigation team was busy dealing with a hostage crisis an hour away from Ferguson.

“In retrospect,” he said, it might have been better to “take some pictures, get whatever angles we can get, collect whatever evidence we can get, and just get the body out of there in a volatile situation like this.”

Then again, he said, “there’s no winning. You take your time, we have this conversation. You snatch and go, and then you’re covering something up.”

That anyone in Ferguson — the town he’d called home since age 10, when his father moved the family from Massachusetts for an engineering job at Emerson Electric — could believe that he would do something so hateful is among the things Jackson has struggled to understand for the last three years.

“It’s heartbreaking to think there’s something in their history or background or experience that would…” Jackson trailed off, shaking his head. “A lot of people think that. It’s bad.”

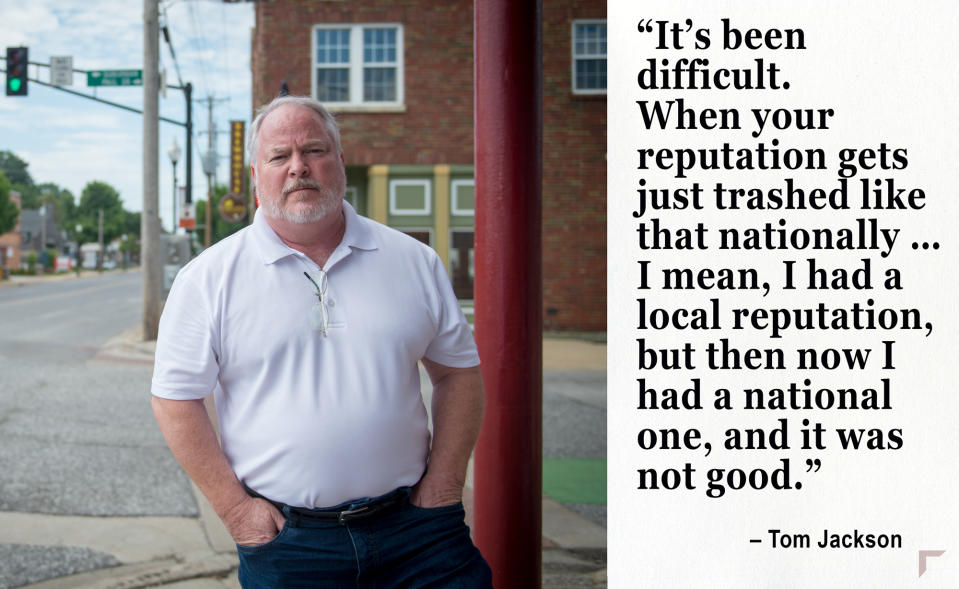

The past few years have been hard on Jackson. Under intense media and public scrutiny as this quiet town of 21,000 was besieged by protests, riots and reporters from around the world, and after the U.S. Justice Department published a scathing report accusing his police department of a number of biased patterns and practices, Jackson succumbed to pressure to resign in March 2015.

Among the findings of the DOJ report were that Ferguson police and courts systematically discriminated against African-Americans, targeting them for traffic stops and arrests and piling on exorbitant fees and fines for missed ticket payments and court appearances.

“It’s been difficult,” said Jackson, who has grown a white beard that matches his formerly blond hair. “When your reputation gets just trashed like that nationally. … I mean, I had a local reputation but then now I had a national one and it was not good.”

Though still visibly shaken by the shooting and protests, Jackson seems relatively at ease on the patio of Marley’s Bar & Grill, a local law enforcement hangout, where he’s greeted warmly by both the staff and his former colleagues, who stop by to shake his hand or give him a hug.

“I remember one local [St. Louis] Post-Dispatch reporter came out to interview me early on, and he knew that I was sort of a liberal kind of guy … for a cop,” Jackson said, lowering his voice as he glanced toward the restaurant where several officers were eating lunch inside.

“You know, you’re the new Bull Connor,” the reporter told him, referring to Birmingham, Alabama’s former commissioner of public safety, a staunch enforcer of segregation who infamously battled civil rights marchers with attack dogs and fire hoses.

“I’m like, how can that be?” Jackson asked, wonderingly. “How can people say that about me?”

In an effort to repair the damage to both his and Ferguson’s reputations, Jackson has written a book called “Policing Ferguson, Policing America,” in which he attempts to discredit the findings of the DOJ investigation and provide insight into some of his own controversial actions.

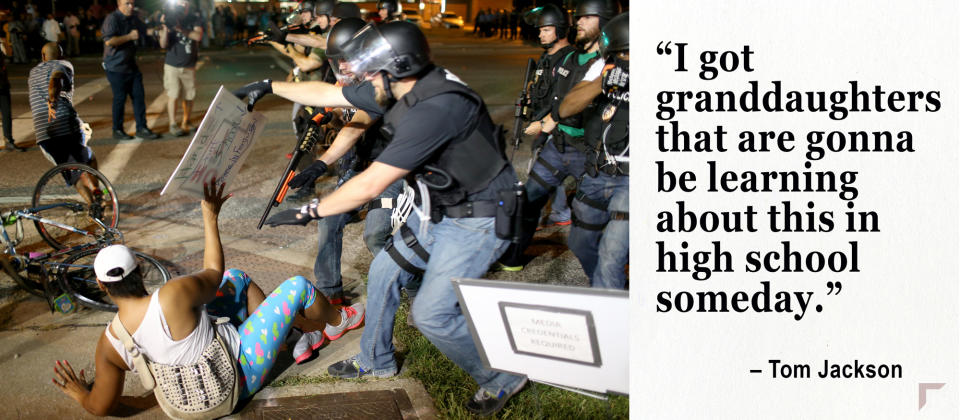

“I got granddaughters that are gonna be learning about this in high school some day.”

Before now, he continued, “there was just one side of the story. The Ferguson side of the story — the Ferguson that existed before Aug. 9, 2014—really wasn’t out there.”

“If this was going on, if this kind of oppression was going on, somebody would’ve told me,” he insists.

Of course, Jackson has plenty of reasons to want to shed the “racism” albatross he’s been forced to carry for the past three years — including that he’s considering a run for public office.

But as steadfast as he is in his belief that both he and the city of Ferguson have been portrayed unfairly by the national media, he also seems genuinely bewildered by much of what happened after he first got the call that one of his officers was involved in a fatal shooting on Canfield Drive. He still wonders at how many people in Ferguson and around the country quickly accepted that “in a densely populated neighborhood, on a hot August day at noon with people out, that there was a kid standing in the street with his hands in the air, surrendering, and the officer just callously pumped lead into him until he was dead.”

‘HANDS UP, DON’T SHOOT!’

There were dozens of witnesses to the fatal encounter between Darren Wilson and Michael Brown. But the one who is credited, for better or worse, with spreading the account that quickly garnered so much outrage was Brown’s friend, Dorian Johnson, who told various media outlets that Brown was on the ground with his hands in the air when Wilson fired.

As the investigation proceeded to unfold, Johnson’s version of events would be picked apart, contradicted and eventually deemed unreliable. But by then, “Hands up, don’t shoot!” had already become a rallying cry for Brown supporters and protesters of police violence nationwide.

Jackson believes the deck was stacked against Wilson and the Ferguson Police Department from the minute Johnson’s account began to spread across social media. The impression it created was reinforced by Jackson’s refusal for six days to identify the officer involved, then releasing the name along with security-camera footage from earlier that day allegedly showing Brown stealing a package of cigarillos from a nearby convenience store. (A new documentary raises the possibility that Brown wasn’t stealing from the store but trying to collect on a debt owed by one of the workers.) To Jackson, that incident implied that Brown wasn’t the “gentle giant” described by his friend, but to Brown’s defenders it was a cynical attempt to blame the victim.

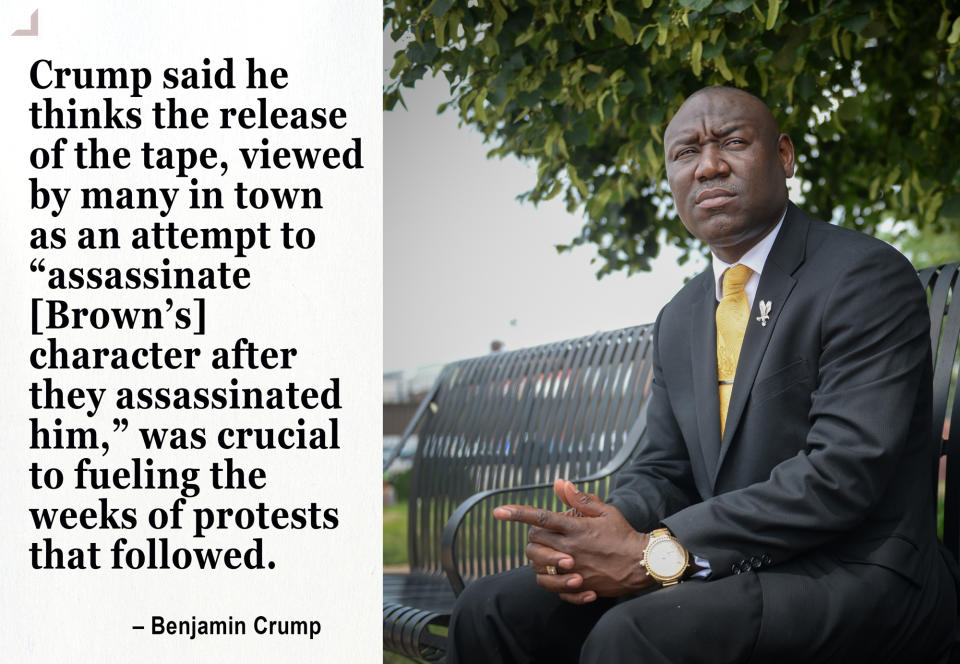

“It’s like they got a playbook,” said Benjamin Crump, an attorney for Brown’s parents, who has represented the families of several other police shooting victims.

In case after case, Crump said, he’s watched as police first try to “sweep it under the rug” by saying the investigation is ongoing. “Then when that doesn’t happen … they start leaking information out piecemeal to try to frame the narrative against the dead person, as if they caused their own death.”

Crump said he thinks the release of the tape, viewed by many in town as an attempt to “assassinate [Brown’s] character after they assassinated him,” was crucial to fueling the weeks of protests that followed.

“It’s like the ultimate disrespect,” he said.

Jackson, for his part, insists he only released the tape because reporters had requested it.

“There was no motive involved in that,” he said. “The kid was dead, there was an investigation going on, why would I want to assassinate his character? He’s still got family.”

The Ferguson story riveted the nation for weeks. Night after night, what seemed to start as peaceful protests quickly devolved into riots, leaving windows smashed, businesses looted and police cars destroyed. Not far from where Brown was shot, a gas station was set on fire.

The initial outrage over the shooting itself continued to grow over the city’s lack of transparency around the investigation, as well as the increasingly militarized police presence. Armored vehicles topped with long-range acoustic devices to disperse crowds barreled down West Florissant as walls of officers decked out in riot gear were seen firing tear gas, rubber bullets and smoke bombs into the crowds.

Jackson maintains that, from the beginning, the violence that erupted after Brown’s death was more than his force of 54 officers could handle. He spends several pages of his book defending the police response. He has harsh words for former Gov. Jay Nixon, who took a number of controversial steps, including deploying the National Guard, declaring a state of emergency and imposing a nightly curfew in Ferguson, drawing criticism from local protestors all the way to the White House. “I don’t think anything that man did helped the situation,” Jackson said of the former governor.

Nixon declined requests for an interview from Yahoo News, explaining via email that he’s chosen to spend his first year out of office reading his journals and reflecting on his time in the governor’s mansion “with the hope of finding meaningful insights.”

“This process is amazingly liberating and hopeful, especially in light of the hyperpartisan, rude tone that appears to have overtaken thoughtful discourse in the public sector in our country,” he wrote.

Jackson’s frustration with Nixon is equaled by his resentment of then Attorney General Eric Holder.

Holder made the unusual decision to travel to Ferguson after 10 days of protests and rioting to reassure residents that the Justice Department would be investigating the shooting thoroughly and fairly.

“I had the hope that a visit by me would have a calming influence,” Holder said to Yahoo News’ Liz Goodwin in an interview. “It was a risky move, because the trip could have been a disaster.”

During his visit, the attorney general met with Ferguson residents who told him about their experiences with a criminal justice system that they believed was unfair and racially biased. Nearly seven months later, many of these complaints would be borne out by the Justice Department’s report. “The criticism seemed to be very widespread and the themes were pretty consistent,” Holder recalled.

He told them he knew first-hand the feeling of being treated as suspicious simply because of the color of his skin.

“I am the attorney general of the United States,” Holder told a group of local community college students in one of his meetings that day. “But I am also a black man.”

He spoke of getting stopped by police as a young man when he was running to catch a movie in Georgetown with his brother, and being pulled over and questioned on the New Jersey Turnpike when he wasn’t speeding. Holder says he didn’t plan to share these experiences, but hoped that by doing so he would convince residents the Justice Department took their concerns seriously.

“I wanted to reassure the community that we would do an independent, thorough investigation,” Holder said. “Looking back at that time, maybe I was thinking there was a way in which, by sharing my own experiences, it would demonstrate to the people … I was coming from a genuine place.”

The civil rights division of the Justice Department investigated Brown’s shooting to determine if Wilson was justified in his use of force. It also launched a separate investigation into possible civil rights violations by the police department. Nearly seven months later, Holder announced the results. Wilson’s actions were not unreasonable under the law, Holder said, because he had reason to fear Brown could disarm him even though Brown did not have a weapon. The report on Ferguson’s criminal justice system was a devastating critique of racial bias, citing among other incidents racist emails sent to and from police and city officials. One email joked about giving a black woman money from “Crimestoppers” to terminate her pregnancy.

Holder said he was surprised to find “that kind of empirical proof of racist attitudes.”

“At one point I thought it was a system gone wrong and that a lot of this stuff had been done in an almost unthinking way,” Holder said of the criminal justice system in Ferguson. “And I think there was a substantial element of that. But … it wasn’t simply a system gone off the rails, it was also a system driven by some of the basest and most deplorable of motivations.”

To Jackson, though, the emails were “twisted” by the Justice Department to justify finding that his department was “a hotbed of racism,” a conclusion that would balance out their decision not to bring charges against Wilson.

Holder “came into town, which he never should have done, and essentially, without saying ‘It’s a bad shooting’ said it’s a bad shooting,” said Jackson. “So what’s he gonna do, back off of that?”

“I can’t say none of it’s true,” Jackson said of the DOJ’s findings. But, he insisted, “the preponderance of it is a narrative that doesn’t exist.”

“Let’s say somebody took everything bad that you’ve ever done in your whole life and wrote it down on a piece of paper and made it look like that was a typical day for you. That’s what they did.”

“It’s hard to even talk about.”

There are a variety of words used in Ferguson to describe what happened here three years ago, depending on who you’re talking to: the uprising, the movement, the crisis, the unrest, the protests, the riots.

Many in Ferguson like to pin the worst aspects of what happened after Brown’s death on outside agitators, people who came from outside the community to cause trouble. That may be true, but before people began to descend on Ferguson from throughout the St. Louis area, and, eventually, the rest of the country, the first rumblings of outrage came from the crowd that gathered immediately at the scene of Brown’s death — people, including relatives of the slain teen, who lived in the residential neighborhood where he was shot.

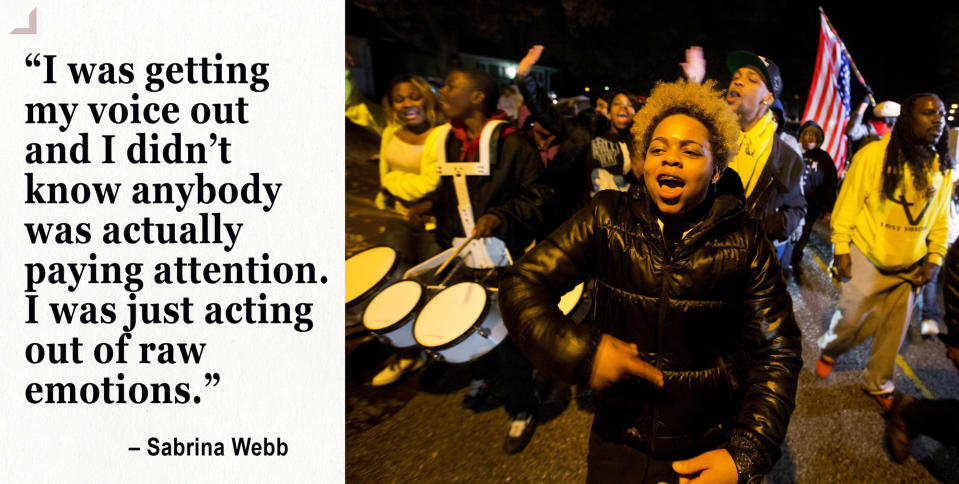

Brown’s first cousin, Sabrina Webb, is still haunted by the site of his body bleeding in the street outside her apartment at Canfield Green.

Webb, now 25, was at work that Saturday when she got a panicked call from one of her roommates telling her that someone had just been shot outside their apartment. Concerned about her friends, Webb says she left work and raced home to find her apartment blocked off by yellow crime-scene tape. One of her roommates was standing on the balcony, pointing at something on the ground.

“I look down, and I kind of like stumbled upon his body,” she told Yahoo News.

In a contrast to the blonde afro that made her easily identifiable among hordes of protesters, Webb’s hair is now pulled back and covered by a khaki baseball cap, the brim curved and pulled down low, casting a shadow over her dark brown eyes.

Only when she heard her roommate yell “That’s your cousin!” did she realize whose body it was.

For Webb, who was often pictured on the front lines of demonstrations that dominated Ferguson for the next several months, protesting her cousin’s death was “was just acting out of raw emotions. I was getting my voice out and I didn’t know anybody was actually paying attention,” she said.

The raw emotions that erupted out of Ferguson soon turned this obscure St. Louis suburb into the epicenter of a national movement. Videos of police shootings spread across social media and protesters took to the streets to in New York, Baltimore and Chicago to protest the deaths of other unarmed black men at the hands of police. Justice Department investigations continued to reveal patterns and practices of systemic bias and excessive force in police departments across the country.

But as the movement grew, it sparked a backlash of its own, driving a wedge between supporters of law enforcement and their opponents, and forcing people to choose sides.

The protests energized the “Black Lives Matter” movement, which had begun in 2012, after the death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Fla., and the acquittal of the local vigilante who shot him. But it has been met with counter-slogans, including “All Lives Matter” (a seemingly innocuous statement that nonetheless is often viewed as minimizing the specific problem of police racism) and “Blue Lives Matter,” meant to convey support for law enforcement officers.

HuffPost reported in March that 32 so-called Blue Lives Matter bills had been introduced in 14 states since the beginning of this year.

As of late May, a Blue Lives Matter bill had passed the Missouri state Legislature and was awaiting signature from Gov. Eric Greitens, who vowed to implement “the toughest penalties possible for anyone who attacks a law enforcement officer.”

“Missouri will show no mercy toward cowards who assault cops,” Greitens said, according to the AP.

Three years after rioting broke out in Ferguson and sparked a national debate about race and policing, former Attorney General Eric Holder told Yahoo News he believes fragile progress has been “set back” in the Trump era as Americans are pressured to choose sides between police and the people they serve.

“It shouldn’t be about choosing, it shouldn’t be about different sides,” Holder said. “It ought to be police and law-abiding citizens against people who want to break the law. That’s the division that there ought to be. Not certain communities — in particular communities of color — versus the police. That doesn’t work.”

The former attorney general, who made addressing the criminal justice system’s historic unfairness to people of color a cornerstone of his seven-year tenure, said he believed the issue has been politicized by President Trump, whose nominating convention dedicated a session to honoring the police under the rubric of “Make America Safe Again.” Trump’s attorney general, Jeff Sessions, a longtime opponent of increasing police oversight, has expressed opposition to Holder’s use of federal consent decrees to reform police departments.

In Ferguson, however, the Justice Department report did result in at least a few immediate changes.

The DOJ’s revelations of biased and predatory ticketing practices prompted a number of reforms at the state level.

In fact, before the DOJ even released its report, the Missouri Supreme Court issued new rule allowing those who can’t afford to pay off fines in full to do so in installments, without risking arrest.

In May 2015, the state Legislature passed a law imposing a 12.5 percent cap on the amount of revenue municipalities in St. Louis County could generate from traffic fines, a significant drop from the previous statewide limit of 30 percent. For cities outside St. Louis County, which was the focus of the DOJ’s damning report, the law set the limit at 20 percent.

In May of this year, however, the Missouri Supreme Court deemed the law unconstitutional because it created different standards for St. Louis County than the rest of the state, setting a unified 20 percent limit on traffic-related fines across the state.

“You don’t see police hiding behind every corner anymore. That has changed,” said Pierson, who served in the state Legislature until this year. Rather than seek reelection in 2016, Pierson launched a campaign for lieutenant governor of Missouri, but lost in the primaries.

A number of new African-American candidates also threw their hats in Ferguson’s 2015 city council race. Two were elected, bringing the number of blacks on the six-member city council from one to three.

In addition to Jackson, who departed the Ferguson Police Department with $96,000 in severance exactly five years after he was sworn in, a number of other officials were either fired or forced to resign because of the DOJ report — including the city manager, two police captains, the municipal court judge and a court clerk.

For the role of city manager, effectively Ferguson’s chief executive, the city council appointed De’Carlon Seewood, an African-American man who previously served as assistant city manager from 2001 to 2007. Former St. Louis circuit judge Donald McClellan, who is also black, assumed the role of Ferguson’s municipal court judge until his death last fall.

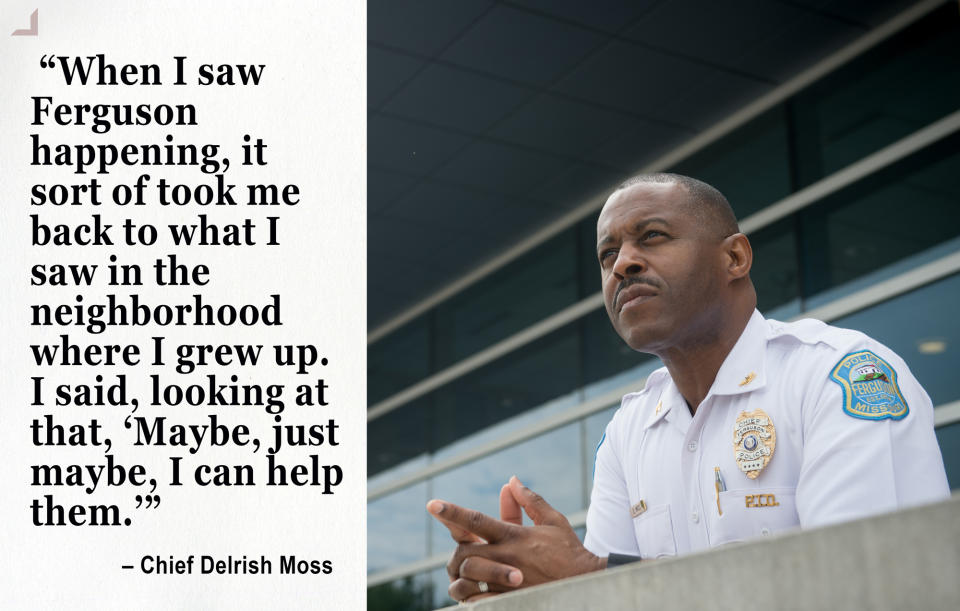

The city cast a much wider net in its search for the new face of its embattled police department, and on May 9, 2016, after 32 years with the Miami Police Department, Delrish Moss was sworn in as Ferguson’s first African-American police chief.

“I think that Ferguson, in large part, was a call to mission,” Moss told Yahoo News from behind a cluttered desk in the office that once belonged to Tom Jackson.

Peeking out from beneath one of several piles of paper in front of him is a cream-colored pocket edition of the New Testament, with gold-embossed font. A framed photo of Moss grinning beside former President Barack Obama sits near the top of his bookshelf.

Moss is no stranger to racial tensions, controversy or the national spotlight.

By the time he joined the Miami police force in 1984, Moss had already watched multiple riots tear through his neighborhood — including those sparked by the acquittal of four Miami-Dade police officers in the death of a black man in 1980 —one of the country’s deadliest race riots since the 1960s.

Years later, he would become nationally recognized as the public face of the Miami police, speaking for the department during a number of high-profile crises, including the controversial repatriation of 6-year-old Elian Gonzales to Cuba, which prompted rioting and fires across Miami’s Little Havana.

“When I saw Ferguson happening, it sort of took me back to what I saw in the neighborhood where I grew up,” Moss told Yahoo News. “I said, looking at that, ‘Maybe, just maybe, I can help them.’”

Like any good communications expert, Moss understands the value of a narrative. He shares a story that was a staple of several news articles published ahead of his move to Ferguson, about the two negative encounters he had with police as a teenager in Miami that inspired him to become a cop.

In one instance, Moss said, “I was called the N word, roughed up, and searched by a police officer,” for no reason.

“At that time, my hope was to become a music education major and become the best trumpet player … better than Wynton Marsalis,” he said. Instead, “I decided I needed to become a police officer” — partly to help the community, partly to become a boss “and fire the two guys that treated me badly.” He believes he succeeded in the first, at least.

Before Moss arrived in Ferguson, city officials spent months negotiating an agreement for a wide range of criminal justice reforms with the DOJ, only to back out, claiming the plan would be too costly. The city council ultimately agreed to the terms of the deal last year, with prodding by a Justice Department civil rights lawsuit.

“It didn’t take a consent decree for me to say we have to rewrite policies,” said Moss, who notes that Jackson inherited many of the bad practices from his predecessor as chief.

On the use of deadly force, Moss’s message to his officers is “I don’t care if it’s legally justified, it has to be absolutely necessary. It has to be the absolute last resort.”

“Police chiefs have an obligation to clearly communicate to their officers what it is they want and what it is they expect from them, regardless of policy,” he said, printing out a recent example of “The Chief’s Daily Dose,” department-wide emails Moss sends every day, usually featuring a personal story or anecdote that illustrates his philosophy on policing.

Moss said that part of his vision for Ferguson is to have “all of my police officers carrying a basketball, a baseball or Frisbee or something like that, and when they see a bunch of kids out playing, get out and play with them.” But in the fallout from the shooting, Ferguson’s 54-person police force has shrunk to 40, leaving little time for bonding opportunities with local youth.

Though Moss insists, “I don’t think about being the first African-American police chief as much as other people do,” he can’t deny that his own experiences with law enforcement as a young black man have shaped his approach to the job.

“Police officers are very powerful people in that they’re the only profession that on a day-to-day basis, exercises more power than the president of the United States,” he said. “At the stroke of a pen, you can take away someone’s freedom, change the course of their life, and determine what jobs they can get.”

“I realize what that power is because it’s been trained on me,” he continued. “So there, being African-American is very significant.”

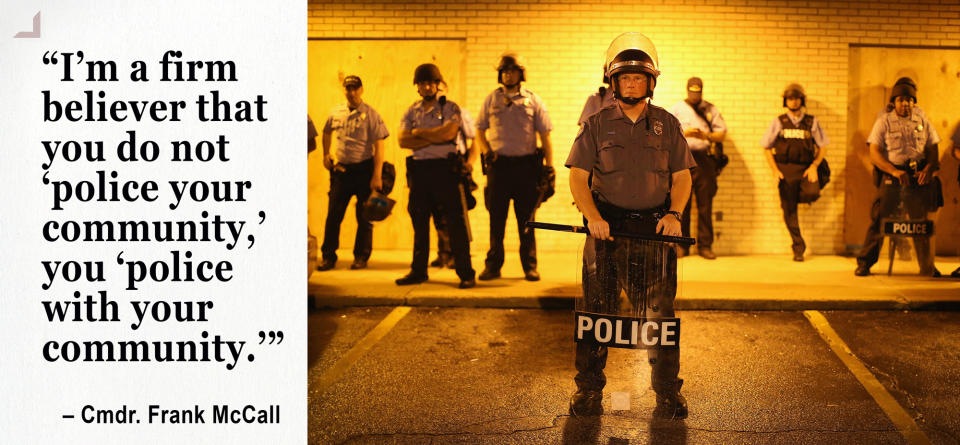

Among the other finalists for Jackson’s former office was Frank McCall, previously the police chief in neighboring Berkeley, who assisted in the regional police response during the riots in Ferguson.

He didn’t get the job, but six days into his retirement, McCall was brought in to serve as the Ferguson Police Department’s community liaison.

“I still feel that I got something left, and that I could contribute something positive,” he told Yahoo News.

As a communicator, McCall is less polished than Moss, but he speaks about some of the realities of policing with a candidness rarely displayed by law enforcement officials.

“I’m a firm believer that you do not ‘police your community,’ you ‘police with your community,’” McCall said. “I think years ago, people were more concerned with policing a community.”

When he first started at the Berkeley Police Department back in the early 1990s, McCall said that in the “us-against-them” climate of those years there was an unwritten rule that officers didn’t shake hands with the public or give out their first names.

“If somebody did, they got in trouble,” he recalled.

“As a new officer, I didn’t understand that,” McCall said, adding that he still doesn’t.

He may no longer go by chief, but now Cmdr. McCall is playing a key role in the implementation of the consent decree, acting as the direct link between the police department and the community where the divisions in Ferguson unearthed by the Michael Brown shooting are perhaps most overtly visible.

As a requirement of Ferguson’s consent decree with the DOJ, the Neighborhood Policing Steering Committee was created as a forum for members of the community to have a say in new policies, hiring procedures and various other aspects of the reform process.

Though described in the decree as a “diverse and broadly representative set of members of the Ferguson community,” among most glaring issues on display at the most recent NPSC meeting last month was that a majority of the 50 or so people in attendance — a larger-than-normal turnout- for the group’s monthly gatherings — were white. Ferguson is more than two-thirds African-American.

“I feel like we should be reaching out to more people that live in Canfield,” said Tiffani Reliford, a longtime Ferguson resident and local activist who has grown increasingly frustrated with the NPSC, told Yahoo News. “To me it’s kind of disempowering the black community if their input is not being heard, right?”

Where and how the group should focus its outreach efforts is just one source of contention among NPSC members, who spent much of last month’s meeting arguing over things like whether to make decisions by consensus or a majority-rule vote, how and when they would determine which method to use and, at one point, what was the group’s actual mission.

By the time McCall and an attorney with the DOJ corralled the group to approve — via consensus — a draft of the police department’s new hiring procedures, one man had stormed out in frustration and several others had threatened to stop attending.

McCall said he worries that the group’s dysfunction might ultimately prevent them from playing a meaningful role in reforming Ferguson’s criminal justice system.

“It would be a shame when you’re in a position to be a part of something that can really set the mode for the communities that have had similar problems,” he said. “Because the only difference is that the problems here just became public. … They exist throughout this country, but they became public here.”

But Moss argues there’s a method to the group’s madness — even if its members don’t realize it.

“Part of all of this is an exercise in healing for the community,” he said. “Policing may have been a problem here, but it wasn’t the only problem. … Prior to the NPSC, most of those people would never have been in a room together having those conversations.”

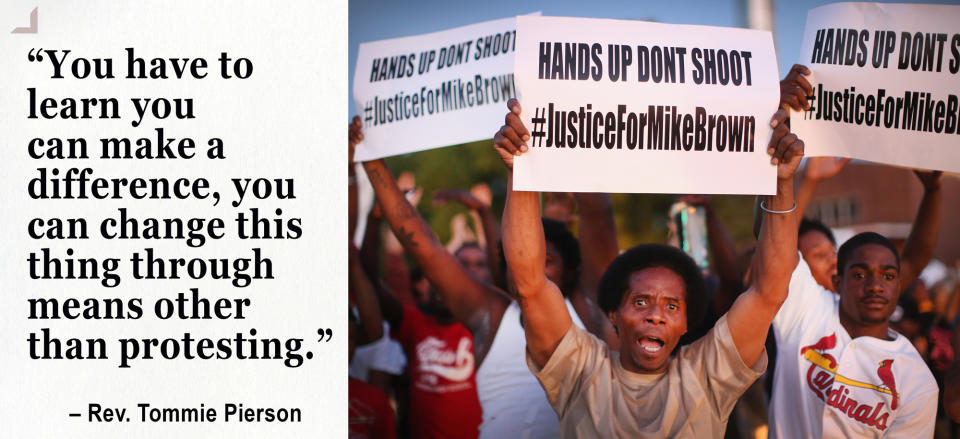

For Rev. Pierson, the biggest challenge since the protests ended has been trying to convince the people who marched against the police to get involved in the political process.

“People in the community can do a lot for themselves if they just … if they learn that they can,” he said. “You have to learn you can make a difference, you can change this thing through means other than protesting.”

But it’s “a slow learning process,” he said, evidenced by the reelection this April of Ferguson’s white mayor James Knowles III. His opponent, an African-American city councilwoman named Elle Jones, had her campaign headquarters at Pierson’s church, but he knew “the only way she could’ve won is you needed a heavy vote from those black wards where Michael Brown got killed.”

“They don’t vote,” he said. “They’ve convinced themselves that their vote doesn’t count and that if they cast it, nothing will change for them.”

Pierson said he tries to change that perception through both his weekly sermon and his own political involvement — which is why he decided last year to run for lieutenant governor, even though, as he said, “Missouri’s a slave state. No African-American has ever won a statewide election in Missouri in its history.”

“Our young people need to get used to seeing somebody like them running,” he said.

“Now more and more African-Americans are looking statewide. So that’s what has to happen. Somebody’s got to pave the way for them.”

Next year, he plans to run for mayor of Bellefontaine Neighbors, a nearby municipality where he resides.

“Now, I can’t preach change and then don’t do something myself in my own neighborhood,” he said.

Michael Brown was gunned down two days before his parents had planned to drop him off at Vatterott College, a career-training school where he hoped to learn heating and air conditioning technology.

This spring, Brown’s mother, Lezley McSpadden, who dropped out of high school at 16 to care for her newborn son, finally received her diploma alongside Michael’s younger sister, Deja Brown.

In the past three years, McSpadden has gone from working behind the deli counter at Straub’s, a gourmet grocery store in suburban St. Louis, to appearing on stage at the Democratic National Convention.

“The plans that I made for today, they no longer exist,” McSpadden told Yahoo News.

“I didn’t choose what happened to me to happen to me, but I know that I have to choose God’s purpose at this point. I have to continue letting him guide my steps.”

So far, those steps have included writing a book, and starting a nonprofit in her son’s name that creates community-based programs promoting a range of issues, including criminal justice reform and health education in low-income communities.

Frustrated with the way the system handled her son’s case, McSpadden said she’s considering running for office to try to change the system to prevent other families from going through the same thing.

“My son didn’t get justice the way he should have,” she said. “Every time something like this happens, I look at the TV, at the family, at the mother and I feel like I just gave my seat up to the next person. … I’m tired of seeing it.”

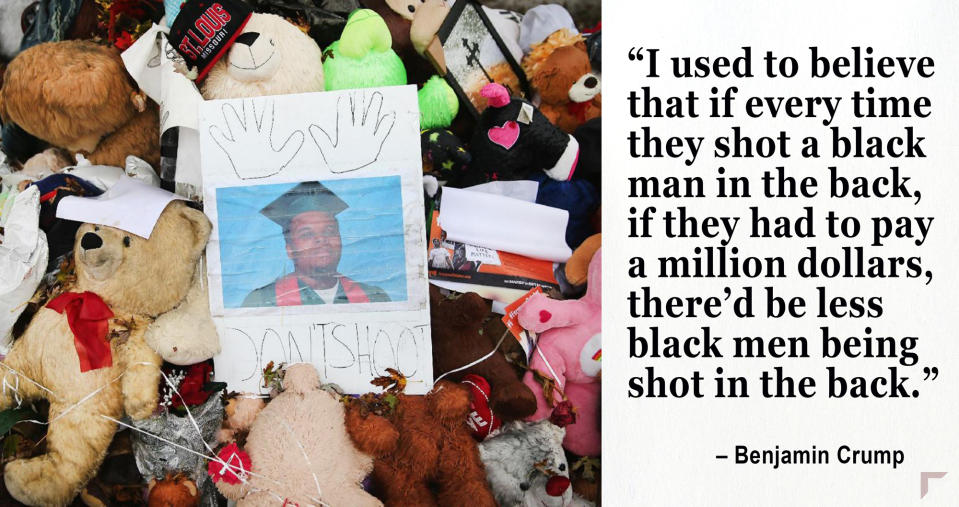

After a grand jury decided not to indict Wilson for killing their son, McSpadden and Brown’s father, Michael Brown Sr., filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Wilson, Jackson and the city of Ferguson. This June, the city agreed to pay the parents $1.5 million to settle the suit.

“I used to believe that if every time they shot a black man in the back, if they had to pay a million dollars, there’d be less black men being shot in the back,” the family’s attorney, Benjamin Crump, told Yahoo News. “That’s not correct, though. I found that theory didn’t hold up because the money is paid by the taxpayers, nothing happens to the police officer who did the killing or the police department.”

Crump became nationally known in 2012 as the lawyer for the parents of Trayvon Martin. He has handled lawsuits for the families of other victims of police shootings, but is losing faith in the system.

“I came to the conclusion, because none of these police officers are going to jail, nobody feels that there’s any consequence for killing an unarmed person of color,” he said, rattling off “a whole rash of new names that have become hashtags,” since Michael Brown, such as Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, Walter Scott, Tamir Rice, Laquan McDonald. “I mean, the list goes on and on.”

Crump said he applauds the young people who’ve continued to speak out against police violence, even after the protests in Ferguson ended.

“You know, the only thing that give me hope is the fact that we aren’t remaining silent,” he said, crediting technology and social media with helping to raise awareness and change the conversation around police shootings.

“Before it was the police word against the dead, black person word. But now, with the advent of technology, we get to see it for ourselves,” he said. “Whether you do something or not, at least you can’t say you don’t know, because you saw it with your own eyes.”

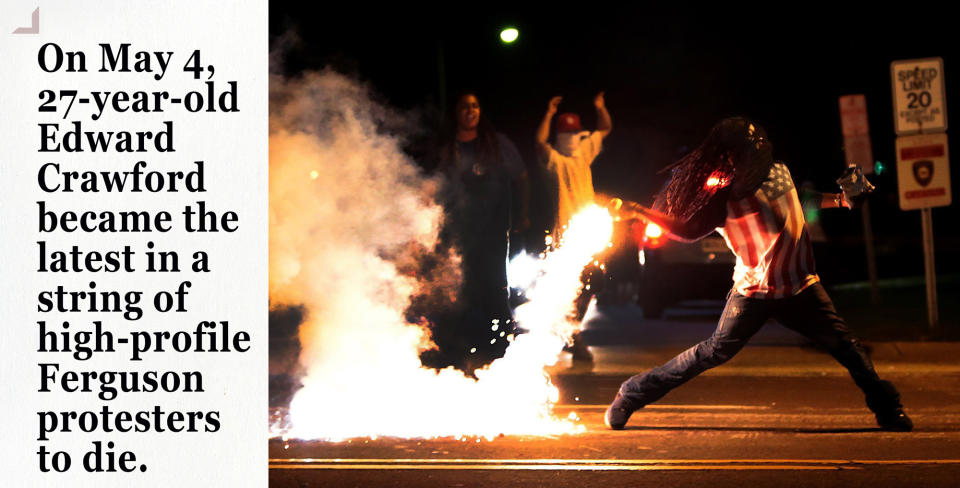

One subject that comes up over and over in Ferguson is the suspicious deaths of a number of young men who were prominent in the protests after Brown’s shooting.

The most recent, on May 4, was 27-year-old Edward Crawford, who became a symbol of the tensions in Ferguson when a local photographer caught him tossing a smoking tear-gas canister back at police. Police say Crawford was in the back seat of a car with two women when he shot himself in the head.

Last September, another prominent Ferguson activist, Darren Seals, was found in a burning car after being shot to death — a scenario eerily similar to the one in which 20-year-old Deandre Joshua, a friend of Dorian Johnson’s, was found burned in a car near Canfield Drive with a single gunshot wound to his head, the night a grand jury decided not to indict Darren Wilson.

There have been no arrests in the deaths of Seals or Joshua, but to many in the black community, the circumstances suggest a sinister explanation.

“The talk around the street is that the police did it,” said Pierson, at whose church Seals’ funeral was held. “That’s what a lot of them believe.”

Though Ferguson has been slow to heal internally, the city has made an effort to clean up some of its more visible scars.

Last month, the Urban League of St. Louis and the Salvation Army opened a community center at the site of the gas station that was burned down in the riots.

Outside the building is a bench dedicated to the slain teen. The plaque beneath the bench is similar to the one that now occupies part of the sidewalk on Canfield Drive, a discreet alternative to the sprawling makeshift memorial of teddy bears, flowers, and notes that adorned the street for almost a year after Brown’s death.

“You would never expect it to be like this now, so serene, so much of an oasis to some people,” Webb said during a recent visit to Canfield Drive. “I would never want to move back over here ever again.”

In the days and months after Sabrina Webb stumbled upon her cousin Mike’s body in the street outside her apartment, life on Canfield Drive became “a headache.”

“I don’t think I ever slept one full night,” she said, describing her neighborhood during that time like an occupied territory, where tear gas permeated the air and officers in riot gear barricaded the street.

“If you didn’t have the Canfield address on your ID you couldn’t get in,” Webb recalled. “Someone like me, I didn’t have that address on my ID, so I would have to sneak my way into my own place where I pay rent.”

Webb said she began to feel increasingly hopeless after a grand jury decided not to indict her cousin’s killer, but decided to stick it out for another year before she realized “it was time for me to go.”

Webb said she returns occasionally to pay her respects to Mike, but walking down the street where his body lay for hours in the hot August sun brings up emotions Webb says she still hasn’t fully processed.

“To relive it over and over again is a haunting situation,” she said. “It kind of disturbs my thoughts.”

Webb said she’s in the process of opening a fine arts studio for underprivileged kids in downtown St. Louis, and hopes to channel her experiences in Ferguson into public speaking. Eventually, she said she wants to go to medical school.

Webb admits that she still has never fully allowed herself to mourn her cousin’s death and now, three years later, the primary feeling she expresses about what happened, and toward Wilson in particular, is rage. She said that watching Wilson’s first interview on NBC News made her so angry that she broke her laptop.

Asked what she would want to say to Wilson if given the chance, Webb said,

“I wouldn’t have any words because you didn’t have any words for him, honestly, before you took his life away. You really didn’t care.”

Wilson has mostly retreated from view, and did not respond to interview requests from Yahoo News.

“His lawyers won’t let him,” said Jackson, who said he still talks to Wilson and that “he’s doing well, actually.”

Asked whether he’d ever been in a situation where he had to use deadly force, Jackson replied: ‘Uh, yeah. I was in the SWAT team for 8 years, undercover for 12 years running a drug task force. Been in a lot of those…”

“For any officer — I’ve never talked to an officer who’s used deadly force that felt good about it. No matter what, even [if] somebody’s shooting at them.”

Jackson is reluctant to comment on the specifics of Wilson’s actions that day three years ago.

“I read the reports and they justified it,” he said.

But for the family and community Brown left behind, even a report by the Department of Justice, authorized and endorsed by the first African-American attorney general of the United States, is not explanation enough.

“I’ll never understand why he killed my son,” said McSpadden.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: