York Vietnam vet's haunting, powerful sculpture reflects the horrors he experienced in war

Point Man 11 Bravo stands about 38 inches tall.

He looks like a Roman centurion, a warrior. He has small orange bicycle reflectors for eyes. His mouth is fashioned from red buttons. His headdress is a brass stanchion from an antique fireplace tool stand, as are his epaulets and other features. His torso, a fiberglass mannequin, is festooned with colorful buttons, his eyeglasses crafted from pieces of a sewing machine.

A green canvas gas-mask pouch containing a plastic toy M-16 and bugle is strapped to his back, a brass peace sign pinned to it. Blank dog tags hang from his neck. A hand-grenade pin dangles from his right ear and a C-ration can opener from his left. He has gears on the right side of his head and a key over his heart, the key to his heart.

He has a haunting look, a piercing intensity that expresses pain and sacrifice and, to some extent, the joy of survival. He is – no other way to put it – a work of art.

Tom Powers began working on Point Man 11 Bravo 20 years ago. He had no plan. He had no intent, no purpose, other than to do it, piece by painstaking piece. It was, he said, “just to have something to do. It was therapy. I never intended to show it to anybody.”

The name comes from the Army’s Military Occupational Specialty code for an infantry soldier ? “someone who didn’t want to be in Vietnam,” Powers said.

It was sitting in his hideaway, a small room above a garage in the south end of York, when a friend, Dave Miller, stopped by.

“What is that?” Miller asked.

Powers wasn’t sure how to respond. It wasn’t done and he had pretty much given up on it. But his friend, he said, “made a big fuss about it.” Miller didn’t know what it was and wasn’t sure he wanted to know what it was. But he thought other people should see it. It had power.

It is a reflection of Powers’ psyche. It wasn’t intentional, he said. It just happened. It was the product of the 12 months he spent in Vietnam 56 years ago, a year that changed him in ways he’s still dealing with, an experience that never ends, he said.

“I have no idea where this came from,” Powers said. “I didn’t know what I was doing. There was no purpose in this. It was just something to pass time, to keep me busy.”

Point Man 11 Bravo, in short, is Tom Powers.

'I never dreamed I'd get through it'

Powers joined the Army at 17, not long after graduating from William Penn Senior High School in 1966. He said he volunteered to be drafted. “I didn’t have to go into the service,” he said. “I was just bored and very naive. I had no idea what Vietnam was about. It sounded exciting to me.”

His mother wasn’t thrilled. She told him he didn’t have to go, that his asthma would have kept him out of the draft. But he told her, “It’s too late.” He’d already signed up.

After basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, he shipped out to Vietnam in June 1968, just a few months after the Tet Offensive, the North Vietnamese attack that changed the course of the war.

When he arrived in country, he was assigned to the 82nd Airborne, Third Brigade, Company B of the 2nd of the 505th. He told the officer that he wasn’t in the 82nd Airborne, as far as he knew, and the officer told him, “You are now. They’re killing them off faster than we can send them.” He also told him. “If you’re living right, you don’t have anything to worry about.”

Eighteen years old at the time, Powers had no idea what he meant.

He was sent to Phu Bai, south of Hue, in the central highlands.

It didn’t take long for him to realize, he said, “this is war.”

"No day was different than any other day,” he said. “They were all bad.”

A little over two months into his tour, he said, “We ran into a real bad day.” His unit was pinned down in a jungle, the canopy so thick you couldn’t see the sky. They hunkered down for three days. “There was no way to get out,” he said. They ran out of water. Three dead lay among the remaining members of the unit.

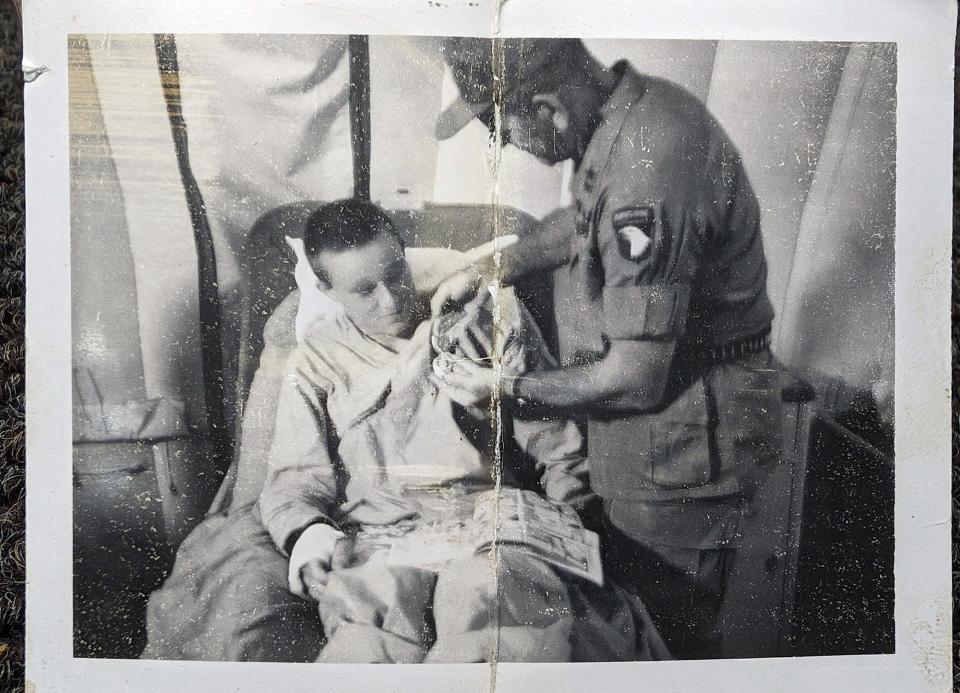

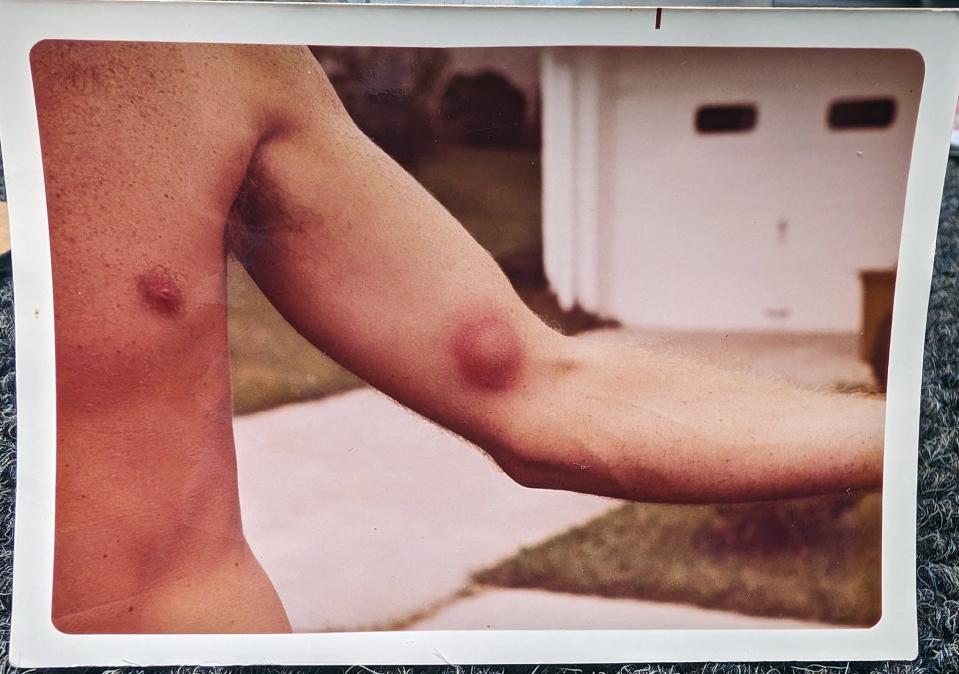

The enemy rained mortar shells on their position, he said. He was wounded, shrapnel embedded in his chest and right arm, according to the report that a medic pinned to his uniform. “I wasn’t in bad shape,” he said, comparatively speaking. Six others were also wounded.

Finally, the officers were able to radio for evac. But the jungle was too thick to land a chopper, the unit used C-4 explosives to clear a landing zone.

He was loaded onto the chopper with the three dead, he said. As the pilot tried to ascend, he said, he kept hitting trees. Another crew member said the helicopter was overloaded and they would need to dump some weight. Eventually, the Huey took off and Powers was taken to the rear.

The surgeons couldn’t remove the shrapnel from his arm, so they stitched him up and left it at that. His rehab consisted of walking around carrying sandbags, he said.

After 30 days, he was sent back to Phu Bai.

He still had nine months to go.

The last few weeks of his tour were the worst, he said. He kept thinking that he wouldn’t get out alive, that he would be killed on his last day in country.

“You don’t think you’re going to make it,” he said. “I never dreamed I’d get through it.”

'The bad days don't leave when you leave'

He came home in July 1969 and went to work for the Postal Service, stayed there for 20 years, and then got a job at a state liquor store for a decade after that.

He soon realized, “The bad days don’t leave when you leave.”

He suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, the year he spent in combat never leaving his thoughts. He still deals with it. He’s a bundle of nervous energy, his anxiety roiling. At 75, he appears to be in good shape, and he seems to be constantly moving.

He lives in a suburban home in Spring Garden Township, near York Suburban Senior High School, but spends a lot of his time in a room above a garage he owns in the city’s south end.

The room was his refuge after he retired from working 23 years ago. “This is where I came to spend time,” he said. “This was my life then. I spent a lot of time in here by myself, pretty much hibernating. That’s how this project started.”

A vet's tale: Pigeon Hills man, 100, survived 39 air missions in WW II. His grandson died in Afghanistan

'Don't panic': York WW II veteran and POW, 100, shares harrowing tale of being shot down over Germany

For 20 years, he sat at a folding table in front of a window and created Point Man 11 Bravo, bit-by-bit, meticulously, even though, he said, he had no plan or overall vision. The piece just came from “up here,” he said, pointing to his head. “This all just came from my head,” he said. “This was my life. Point Man was a big part of it.”

He said, “It’s what occupied me. I had a lot of time to kill.” He hadn’t realized he had been working on Point Man 11 Bravo for 20 years. “I didn’t think about the time going by,” he said. “I was just getting through life.”

The table is strewn with seashells and assorted buttons. (He used to do some upholstery work and got a deal on the buttons, buying 40 pounds of them for five bucks from a supplier in Harrisburg a while back.) A small, desktop triptych of the Last Supper rests close to the window.

The sculpture came together in a seemingly haphazard fashion, flowing from his mind in a way that seemed chaotic, but made sense, he said. Some of the pieces that make up Point Man 11 Bravo seem random – a play money $100 bill tucked under its left epaulet, for instance – and they may be, but the result reflects Powers’ mind. He’s not even sure what the $100 bill means. “It wasn’t intentional,” he said. “All of this came about for no reason.”

He points to a single whisker made from a three-inch-long piece of wick on the sculpture’s chin and says, “Why did I do that? I don’t know.”

'This should be in a museum'

For years, Powers never showed Point Man 11 Bravo to anyone. It was personal, he said, and he wasn’t sure anyone would get it. “It was never going to go anywhere,” he said. “I was just doing it to have something to do. It kept a purpose for me.”

When Dave Miller stopped by and saw Point Man 11 Bravo, Powers said, “I had pretty much given up on it.” It wasn’t finished, but after Miller “made a big fuss about it,” he said, “I sort of finished it. If my friend wouldn’t have seen it, it would be over there collecting dust.”

Miller, who has known Powers for 25 or 30 years or so, meeting him at a motorcycle event and striking up a friendship, said, "I was blown away by it."

Miller even offered to buy it from Powers. Powers told him he wasn't interested in selling it. "I can't let that go," Powers told him. "I have a lot of time in it and it's therapy for me."

Miller, retired from defense contractor BAE, took some photos of Point Man 11 Bravo and shared them with his older brother, who had served with the Marine Corps in Vietnam. "He picked out a lot of things in it," Miller said, "like the grenade pin in his right ear and the O-37 (can opener) in his left ear."

Miller offered to give Powers a pair of yellow glass reflectors he had on hand to replace the orange reflectors serving as Point Man 11 Bravo's eyes. Powers declined. The orange reflectors mean something, he told his friend, the toxic Agent Orange defoliant troops were exposed to in Vietnam. "Tom knows exactly why he put that there," Miller said.

Miller encouraged Powers to display Point Man 11 Bravo. The first public display was at a VA Christmas party, Powers said. A VA psychiatrist – a woman “who has worked on people’s heads for 30 years,” he said – walked around it twice and told him, “This should be in a museum.”

Not everybody loved it. When his son, an accountant by education who surfs for a living in Hawaii, saw it, his reaction was visceral. Point Man 11 Bravo disturbed him. He told his father, “I don’t know what that is and I don’t want to know what it is.”

His son told him he never wanted to see it again.

'A big part of me'

On March 29, Point Man 11 Bravo will be on display at the ceremony for National Vietnam War Veterans Day at the York Fairgrounds. (March 29 was selected as the date for the national holiday because it was the day the last combat troops left Vietnam in 1973.)

For a work of art that’s so personal – a self-portrait of his psyche, he said – other vets who had seen Point Man 11 Bravo see their own story in his visage. Other vets, Powers said, recognize the bond they share.

For Powers, creating Point Man 11 Bravo was therapeutic, but it did not heal all old wounds.

“I’m not over ‘Nam and I never will be,” Powers said. “It’s never over. How I got through it, I don’t know. It never goes away. It’s just a big part of me.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: York PA Vietnam vet's haunting sculpture reflects horrors of the war