York WW II veteran and POW, 100, shares harrowing tale of being shot down over Germany

Don’t panic.

Those words came to Harold Pressel moments after flak from German anti-aircraft fire ripped through the left wing of his B-24 Liberator over Germany, hitting the heavy bomber between the two massive prop engines, piercing the fuel tank.

Pressel was perched over a pair of .50-caliber guns in a Plexiglas turret mounted on the aircraft’s tail when the flak hit. That was his job, tail gunner.

It was Feb. 7, 1945. The crew had just finished its bomb run, dropping its four tons of bombs on a refinery in Floridsdorf, just across the Danube from Vienna, Austria. Pressel remembers seeing the Danube, a sight that remained lodged in his memory, the river romanticized by the classical piece by Johann Strauss II “The Blue Danube.”

The bomb run did not go according to Hoyle. On their first pass over the target, the Germans had set off smoke bombs to obscure the refinery. The B-24 had to loop around for a second pass, dropping its bombs and dodging anti-aircraft fire while setting a course back to the base in Italy.

Then, he said, the flak struck and “we got hot." The plane was losing fuel and going down, dropping from 26,000 feet to 14,000 feet in a matter of seconds. They knew they couldn’t get over the Alps to return to Italy so the pilot set a course for the Russian lines, hoping they could bail in Allied territory. They made it across the Austrian-Hungary border before the pilot “couldn’t hold it anymore.” The aircraft began wobbling, he recalled. They knew they had to get out.

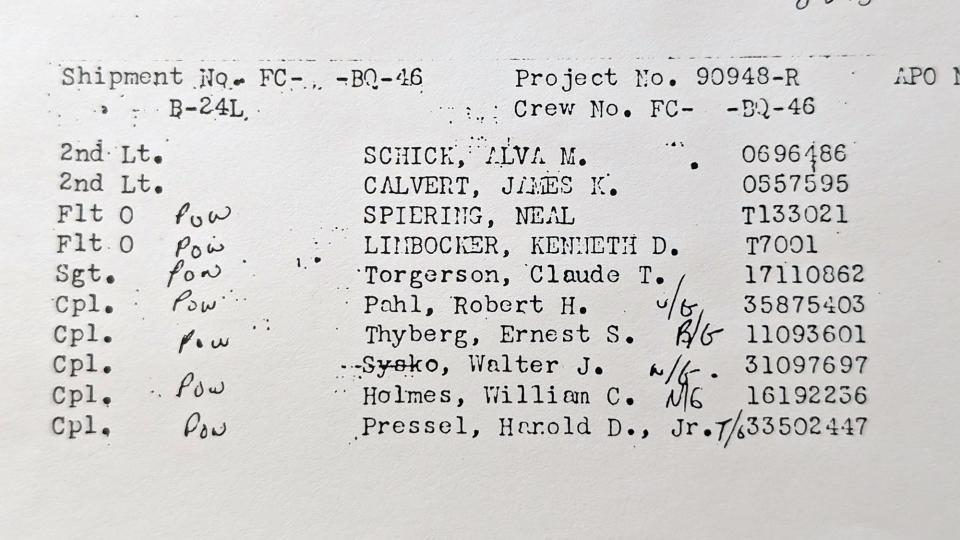

The B-24 Liberator was nicknamed “the flying coffin,” because it has one hatch at its tail and if it was hit, much of the crew had to navigate a narrow catwalk through the bomb bay to the plane's rear. Fortunately, the crew of the plane christened the Ol’ 45 was able to get out. The crew, two pilots, two officers and six gunners, all bailed.

Pressel stepped from the hatch, his right hand gripping the D-ring to release his belly chute. He recalled the words: Don’t panic.

His body spun as it plummeted toward the fast-approaching ground. He had to get out of it, so he spread his arms and held his legs together to come out of it. It worked.

He pulled on the D-ring to release the chute.

Nothing happened.

He was dropping at about 120 mph. The ground was getting bigger ? quickly.

He thought: Don’t panic.

'Keep moving'

Harold Dewey “Bud” Pressel Jr. recalled that story as he sat at the kitchen table of his ranch home in the eastern suburbs of York, finishing his lunch – pizza.

He has lived there since 1970, one of the first homes to be built in the development that formerly was farmland, pastures and woods. He remembers when it was open land; when he was a kid, he and his friends camped in a field not far from his home.

He gazed out the picture window overlooking his backyard and recalled that when he first moved there, the old farmhouse still stood nearby. It was a huge clapboard structure, built by Mahlon Haines, the Shoe Wizard who made his fortune in footwear and, later, real estate. The development is named for him, Haines Acres.

He’s a trim man, in good shape. He has a walker nearby but doesn’t really need to use it. You would never guess that, in February, he will be 100 years old. His mind is sharp. He goes to the gym every day and works with a trainer once a week at the Veterans’ Administration.

Not long ago, he was hospitalized with a bleeding ulcer, his son, Jim, said. The doctors were not hopeful about his prognosis – mostly because of his age – and suggested to his family that they look into hospice care. Pressel recovered and was soon back in his ranch house in Haines Acres, doing fine.

Part of his longevity is genetic – his mother lived to 85 and his father to 94. But he said the key to staying healthy is “keep moving.”

You could also say it is also don’t panic.

He always dreamed of flying

Pressel was born Feb. 3, 1924, the third child of Harold and Evelyn Pressel’s seven children. He was the oldest of their two sons. The family lived on Lehman Street on the city’s East End. His father worked as a salesman and his mother in a sewing factory.

York was a small town then. It had trolleys and a roundabout square, and everything was downtown, from the Central Market House to the department stores where everybody shopped. It was also the entertainment center, with the Strand Theater and its movies and stage shows and the Valencia Ballroom, whose stage featured a lot of the big bands of the era. (“I got to see most of them,” Pressel said.)

When he was a kid, he and his friends would head east to play and explore the woods and pastures east of town, land now covered by suburban development.

He recalled that there was an airport – more like an airstrip with a runway, a control tower and a few hangars – east of town in a pasture off East Prospect Road near a path that would later become Haines Road. Aviation was in its early days, at least in his hometown of York, and hanging out to watch the planes take off and land was a novelty, almost a spectacle.

“We used to hang around the airport a bit and try to get a ride in an airplane,” he said. “Never did.”

Some years later, he would get to fly.

'I liked what I was getting into'

In 1943, he dropped out of William Penn Senior High School during World War II and went to join the service.

He and a couple of buddies went to Baltimore to sign up for the Merchant Marines. He took the initial test and passed and was told “they would call us,” he said. “In the meantime, I got a letter from the draft board.” He informed the draft board that he had signed up for the Merchant Marines, but they told him it was too late, that he should have told them that before the draft notice was issued.

He was inducted at Fort Meade in Maryland where he boarded a southbound train. “They kept dropping people off going south,” he said. “I stayed on until we hit Miami.”

He did basic training at the airfield on Miami Beach, a new member of the Army Air Force. The barracks were the big hotels on the main drag and the base had formally been a golf course, taken over by the Army during the war. When the new soldiers marched to breakfast at the crack of dawn, they would sing, eliciting complaints from civilians staying in one of the remaining resort hotels. The hotel manager lodged a complaint with his sergeant, who told him that if his boys' singing bothered his guests, maybe they’d like to hear singing in German. “That shut him up,” Pressel recalled.

At first, he said, he was assigned to mechanics school, learning to repair trucks and such. Then he went to radio school and eventually to gunners school, training as a gunner on a B-24 heavy bomber.

He got to fly. “I think I liked it,” he said. “I liked what I was getting into.”

Before he shipped out overseas, he married. He met his future wife when he was dating her sister. They were at a skating rink when he met her sister, Grace Myers. “I saw her sister and thought, ‘That’s what I want,’” he recalled. His future wife’s sister seemed to accept it. “I didn’t get in too much trouble,” he said.

In May 1944, his unit shipped out for Italy and the war.

'Don't panic'

Pressel was assigned to Squadron 825 of the 484th Bombardment Group, flying out of Torretta, a small town near the crook in Italy’s boot heel. There were so many air fields in the heel that take-offs and landings often overlapped, and pilots had to be vigilant not to hit incoming or outgoing bombers.

The squadron's first mission was a strike on a refinery in Floridsdorf, just over the Danube from Vienna, Austria. During the mission, Pressel was in the turret between the twin rudders of the B-24. On the bomb run, he could see the dark clouds of flak exploding all around the airplane. Strangely, he said, he wasn’t frightened. He was calm. He reasoned he had a job to do and he he just had to do it.

After dropping its bombs, the B-24's oxygen system failed, he said. The plane usually flew at 25,000 to 30,000 feet and the crew required oxygen to remain conscious. They also wore electrically heated flying suits to stave off freezing temperatures that could reach 20 to 30 degrees below zero.

The pilot left the formation and dropped to 10,000 feet, a dangerous survival move. It was not an option. The crew had to breathe, but flying solo at such a low altitude left the plane extremely vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire and gunfire from German fighter aircraft.

They made it back to the base, Pressel said.

Not long after, on Feb. 7, 1945, he was flying just his third mission. The target was the same. His crew dropped its bombs and then was hit with anti-aircraft fire. Pressel and the rest of the crew bailed.

The D-ring that was supposed to release his belly parachute ripped free. He remembered looking at the ring in his hand and its attached wire that was supposed to free his chute flapping helplessly as he plunged to the ground.

“I told myself, ‘Don’t panic,’” he said. “It worked.”

He reached down and ripped the cover off the parachute pack. The small pilot chute fluttered out, followed by the main parachute.

Soon, he was floating toward the ground.

He remembered the training he and others received in Miami. It was far from complete. He recalled that their training for bailing consisted of being led into the stage of an auditorium. Some mats had been set down in front of the stage. They were told to run off the stage, land feet-first on the mat and roll. “They told us, ‘That’s your parachute training,’” he recalled.

All the crew was able to bail. The pilots bailed last and landed on the frozen surface of a lake, the same lake the B-24 crashed into and sunk below the ice. They were rescued by Russian troops.

Pressel and the rest of the crew were not so lucky. They all survived, but they came down in enemy territory.

He landed in a cornfield, flat on his feet, falling onto his back, he said. Fortunately, he said, he landed between the rows of cut corn stalks and was not injured, except for an eardrum that shattered during the free fall.

Pressel remembers five Hungarian guys stood over him in the corn field. It was like they were waiting for him, he said. They took his watch and a bracelet with his wife’s name engraved on it. He asked for his watch back, he said, but they wouldn’t give it to him. They did give his bracelet back.

They took him and his fellow crew members to a nearby farmhouse where a German officer awaited. He looked like a Nazi officer out of a movie, his uniform pristine. He asked Pressel a lot of questions. Where was his squadron headquartered? What was their mission? How many bombers were in the group?

Pressel answered every question with the same answer: Name, rank and serial number.

The Germans flew Pressel and his crewmates – all of them had survived bailing out of the damaged Liberator – to Frankfurt. The Germans interrogated them but got nowhere. “They threatened that they’d do this or that if we didn’t answer,” Pressel recalled.

They put the men in solitary confinement and continued to pelt them with questions, Pressel said. The crew held firm – name, rank and serial number.

They loaded the crew, along with other prisoners, into boxcars for the prisoner-of-war camps. At the time, Pressel said, they had no idea about the meaning of that ? that the Germans had sent millions of people on a journey to death on boxcars.

Their first stop was Dulag Luft, a camp near Wetzlar, Germany. From there, they were transported to Stalag 13 near Nuremberg. During that trip, their train was strafed by three P-47 fighters. One pilot spotted the Red Cross atop the train cars and pulled the others off. “We lost a few guys in that,” he said.

Pressel wound up at Stalag 7-A near Moosburg, a camp that housed about 15,000 prisoners. “They didn’t treat us too bad,” he recalled. “They knew the war was winding down and they were losing.”

At the camp, one of the guards asked Pressel whether he could help him get to the United States. The guard, a sergeant, asked him whether he wanted a shave and produced a broken straight razor. Pressel shaved and as he did, the sergeant told him about his brother, who had been captured by the Americans and sent to a POW camp in the United States. “He said how much his brother liked it there and wanted to stay,” Pressel said. “He asked me to be a reference so he could come to the States. I told him I couldn’t do it. It was against the rules. He said, ‘I’ll make it to your country someday.’ I’m not sure if he ever did.”

The camp was crowded – a lot of prisoners were housed in big white tents instead of wood-frame barracks – and smelled horribly, mostly of human waste and body odor and death. Food was scarce. Pressel remembered being hungry constantly. There was a Limberger cheese maker across the road and the owner brought some over to the camp, he recalled. “Some guys wouldn’t eat it,” he said. It smelled so bad that those who did eat it had to eat it outside. “I took it,” he said. “It was so horrible.”

The prisoners also subsisted on bread made from sawdust and insects. He remembered scraping mold from the bread and sweeping insects away. After a while, the mold and bugs didn’t matter. He was so hungry, he said. “We got tired of pushing the bugs away, so we ate them,” he said.

On April 29, 1945, Gen. George Patton liberated the camp.

He set up a field kitchen – had it operating within a couple of days – and fed the prisoners. The prisoners, Pressel said, asked the servers to pile their trays high, but they would only let them take so much, saying they could come back for seconds later. Starvation had shrunk their stomachs and Pressel said, “They were afraid we wouldn’t be able to keep it down.”

Pressel can’t remember what that first meal was, but “it was good.”

He went to the coast, crossed the English Channel and was soon on his way home.

In June 1945, the troop ship steamed into the New York harbor. They were greeted by a fleet of civilian boats, all blowing their whistles. Some reporters from New York boarded the ship to interview officers of the First Army who were aboard. The officers told the reporters to talk to the POWs.

The POWs were transported to Fort Kilmer in New Jersey. There, they boarded a train for Miami and 90 days of rest and recreation.

Pressel did some fishing and relaxed in Miami Beach and then came back home. He got a job at the Pennsylvania Freight terminal on North Street and settled in.

Another veteran story: Lawrence "Gump" Bolin draws pictures about the horrors he witnessed during World War II

Not long after, he received a telegram notifying him that his service wasn’t complete. He was sent back to Miami, where he spent the last month of his service to his country sightseeing and fishing. “Everything was free,” he said.

He said he spent the time recovering. “I was just cleaning everything out, forgetting it,” he said.

He was transferred to the Olmstead Air Base in Middletown, Pa., a 40-minute drive from home. A month later, on the Saturday after Thanksgiving 1945, he was honorably discharged, having been promoted from corporal to sergeant before he left the service.

He returned to Grace and got a job in the Motter electrical shop in York. He and Grace had two sons, Jim and Gary. He eventually went to work in construction with the Bechtel Corporation, working as an electrical superintendent on nuclear power plant projects. Among the plants he helped build were the Peach Bottom Atomic Power Station in southern York County, Three Mile Island near Middletown and the Limerick plant outside of Philadelphia.

A Vietnam story: Vietnam vets reunited after 50 years

'A good life'

He retired in 1989.

Grace passed away in 2021. She was 99. They had been married 77 years. He has four grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and one great-great grandchild.

Since his service, the United States has been involved in at least five more wars. He often thinks about the men and women serving in those war zones. “The only thing I can think of is that some wars are necessary, but I want everybody to get back,” he said. “It’s not good when they don’t.”

Recalling his own service, and being shot down, he said, “I had my concerns, but I always felt calm. I could say I was nervous, but I always felt calm flying missions. I just had the idea that I was going to make it. I just had to think positive.

“I never thought I’d make it to 100. I didn’t think I’d make it to retirement sometimes.”

He said, “I had a good life. You just have to keep moving.”

And don’t panic.

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: York PA WW II veteran survived plane being shot down by not panicking