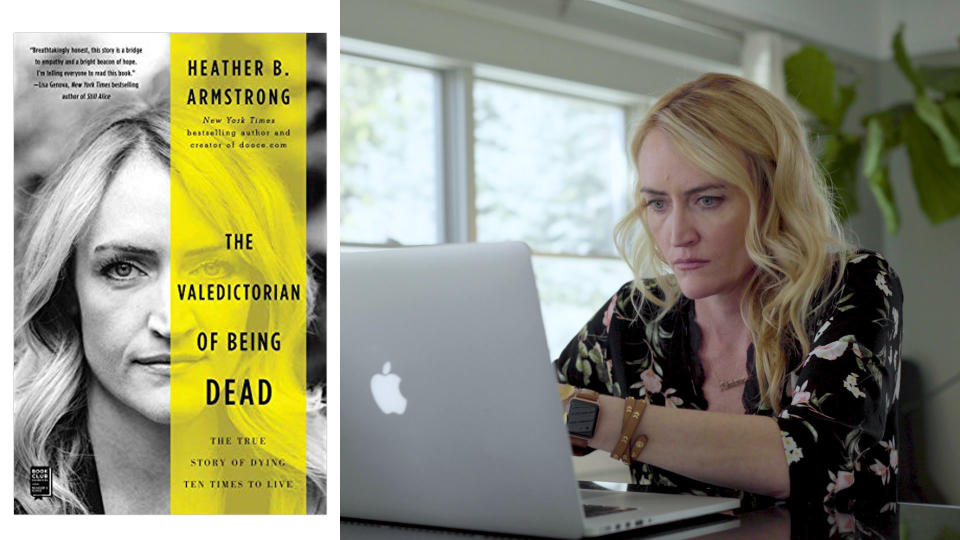

'Mom blogger's' book describes journey back from 'death' — and new hope for treating depression

Heather B. Armstrong did not literally die during an experimental treatment for her depression. Not even once, and certainly not 10 times, despite having written a memoir titled “The Valedictorian of Being Dead: The True Story of Dying Ten Times to Live.” But during her suffering she had wished for death, and during the treatments, her brain wave pattern looked like death, and her recovery felt a lot like coming back from the dead.

Armstrong, 43, was one of 10 patients in the first round of a clinical trial that used the powerful anesthetic propofol (the drug that killed Michael Jackson and that is routinely used for colonoscopies) at doses high enough to cause her brain activity to virtually cease, as a treatment for her profound and resistant depression. Her book is the story of that journey, an intimate and gritty tale of how she did something desperate and, as she puts it, “insane” because it seemed the only path back to sanity.

This is not the first time Armstrong has written about depression. She became one of the earliest power bloggers an internet generation ago when she live-blogged her postpartum depression after giving birth to her first daughter. She posted throughout her stay on the psychiatric ward, her then husband, Jon Armstrong, transcribing her handwritten entries because patients didn’t have access to a computer, her audience growing to more than 40,000 people a day.

Once called the “Queen of the Mommy Bloggers” in the New York Times Magazine (full disclosure, I wrote that story, so I guess I gave her that name), she earned a good living for more than a decade, selling ads to go alongside her daily musings on parenting, marriage, leaving the Mormon faith — and struggling with depression.

“‘Our Lady of Perpetual Depression’ is currently the tagline on my website,” she said during an interview with Yahoo News in the sun-filled and comfortable Salt Lake City home she shares with her two daughters and her brand-new love. “Depression is absolutely a through line in my career.”

Armstrong had suffered from depression in high school, but it worsened in college, to the point where she announced she was dropping out of Brigham Young University. With the help of antidepressants, she recovered and did well for years, during which she worked in digital design, got married and began writing her blog. Called dooce.com (coined because she mistyped the word “dude” in a work email once), it took off in 2002 after her boss discovered her using it to snark about her workplace and very publicly fired her. To be “dooced” became a term to describe the new phenomenon of being axed for something you write online. (It’s a Trivial Pursuit question, and on “Jeopardy.” “My mother is very proud,” she says.)

When she became pregnant in 2003 she stopped her medication. She assumed she would stop blogging entirely after giving birth, because “how could I have time to write a blog when I had a baby?” she says. But the day Leta was born, daily page views jumped to 40,000 and grew from there, eventually to upward of 100,000, as she chronicled her descent into postpartum depression and her journey back from it. When pregnant with Marlo, who was born in 2009, she remained on medication at the advice of her doctor, and did not have a postpartum episode. She stayed on the medication for the 10 years since, though, as her book chronicles, they stopped being effective.

As familiar as she might have been with the illness, her latest round of depression, which began in October 2015, was different. She had been divorced from Jon, who had moved to Brooklyn, leaving her a single parent of two school-age girls, the pressure of which she compares to “juggling knives.” She had taken a break from her blog, because the internet had gotten harsher and, she says, she’d become tired of creating artificial situations to put her children in so she could highlight some sponsor’s products.

In the fall of 2015, she agreed to serve as a guide to a visually impaired runner during the Boston Marathon the following spring. She was maintaining a strict gluten-free vegan diet at the time, and the relentless pace of training with what she now realizes was improper nutrition, plus the stress of single parenting, “put me in a hole I couldn’t get out of. I got worn out and down and just deeper and deeper and deeper into a depression.”

Waking up every morning, she writes, “I would shoot straight up and gasp for breath as my anxiety set fire to every molecule of my body. I woke up soaking in a vat of acid, that my flesh was covered in flames. The thought of what I needed to get done and what I hadn’t gotten done and every potential thing that would ever need to be done screamed in my ears, voices all talking over each other in angry, disappointed tones, all echoing and thundering and crashing into cymbals. … The low whisper, becoming a roar, that they would be so much better off without me.”

She did finish the marathon, and she thought that the end of training would be the end of her suffering, but the depression didn’t lift. “I only have two hands,” she would sob to her mother daily, usually calling from inside her bedroom closet, hoping her clothes would absorb the sound and keep her children from hearing. “Please, just let me be dead.”

Armstrong stresses that she never actively wanted to kill herself. “I knew that I couldn't leave [the girls],” she says. “And so I never made a plan to kill myself. That was never in my head. But I wanted to be dead. I thought how amazing would it be to not feel what I’m feeling ever again. And the only way to accomplish that would be if I were dead.”

She knew she needed help, she says, but feared that seeking it — potentially being hospitalized, certainly making it clear how fragile she was — would result in losing custody of her daughters. “I didn’t want to do anything to jeopardize” having full custody, she says. “I was willing to live feeling sad as long as I had them in my care.”

For 18 months she went through the motions of the day, doing all the thing she needed to do for Marlo and Leta, but every step felt like a battle, a mountain climb. Forgetting the milk cartons Marlo needed for a school art project led to hours of self-recrimination about her worth as a mother. Arguments over practicing the piano felt like a soul-crushing monumental failure.

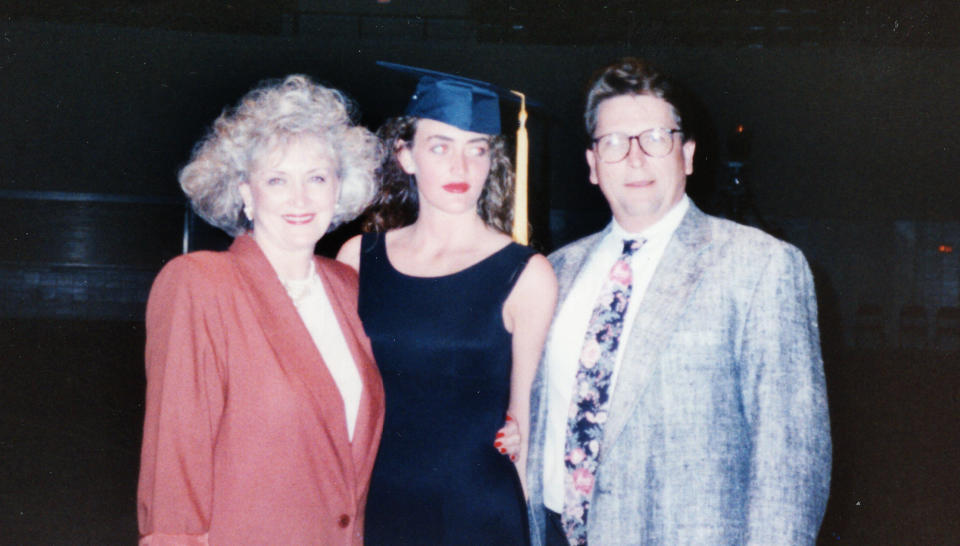

One night early in 2017, after a particularly rocky evening, “I remember crawling across the floor … and reaching up for the phone and calling my mom and saying you have to come be with me because I’m very, very scared about the feeling that I’m having.” Her mother and stepfather drove the 40 minutes from their house, keeping Armstrong on the line the entire time, for fear of letting her hang up. When they arrived, they put her to bed, and in the morning stood next to her while she made an appointment with her psychiatrist, who she had not seen in over a year.

Drug-resistant depression is what clinicians call it when a patient does not respond to two different medications after being on each for four to six weeks. Of the 16 million new incidents of depression in the United States each year, about one-third are treatment-resistant.

There is an effective next treatment for these patients — electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, during which electric currents are passed through the brain while a patient is under general anesthesia, intentionally triggering a brief seizure. The resulting changes in brain chemistry are highly effective — a success rate of 75 percent — at reversing depressive symptoms. However, “patients often don’t choose to get ECT,” says Scott Tadler, MD, an associate professor of anesthesiology at the University of Utah, and a member of the research team that conducted the propofol trials that included Armstrong as a subject.

The reasons for reluctance to try ECT varies, Tadler says, and include everything from “they’ve seen movies like ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,’” in which Jack Nicholson’s character’s personality is unrealistically wiped clean by the procedure, to “fears of the side effects, which include attention deficits, memory loss, migraines.”

The search has long been on for a next way of helping patients for whom medications don’t work. The Food and Drug Administration recently approved a ketamine-like nasal spray, but only for use in a certified doctor’s office or clinic, with at least two hours of monitoring with each treatment, because although the drug works rapidly against depression, it can also cause hallucinogenic side effects.

Like ketamine, propofol was first introduced as an anesthetic. It works quickly and wears off quickly, making it a go-to for such procedures as colonoscopies. It is thought that ECT works because the induced seizure creates a phenomenon known as “burst suppression,” in which brain activity quiets almost entirely, essentially creating an emotional reset. This led researchers to wonder whether it was possible to create that same brain pattern without the seizure, since most of ECT’s side effects come from the seizure itself.

Two decades ago, there were a few small studies using the anesthetic isoflourene, but those were stopped because the drug was found to dangerously decrease blood pressure, among other side effects. But propofol — when properly monitored by an anesthesiologist, which, Tadler stresses, was not the case for Michael Jackson — is considered a particularly safe and effective medication, and Tadler and a colleague, Brian J. Mickey, MD, hypothesized that it might be a better one for this purpose.

When Armstrong finally met with her psychiatrist, she not only feared she would lose custody of her children, but also that he would recommend she try ECT. Instead he offered to enroll her in a small “open label” trial, a first step in this kind of experimentation, in which there is no placebo, no control, no attempt to “double-blind” physicians and patients so no one knows who actually gets the drug. Instead, 10 patients would be given a series of 10 propofol infusions each, three times per week, to the point where their electroencephalographic activity would be suppressed for 15 minutes. The goal was to determine whether the treatment was tolerable and effective enough to warrant a full clinical trial.

“When he explained the study to me, he casually mentioned that yes, there is a slight possibility of death but you’re not going to die,” Armstrong recalls. “He leaned across the room and emphasized to me that this would work.” Even though she knew he could not be sure, since she would be one of the first ever to try this, his words alone made her optimistic. “It was the first glimmer of hope that I had had in 18 months.”

And yes, she says, she understands that she did not technically die during the treatments. “Burst suppression” is not “brain death,” Tadler emphasizes, though he understands that “to Heather it was in many ways like death and rebirth.”

For her, it worked. She was the third patient in the trial, one of the six who responded well, one of the five who was still better six months later, and one of the three who remain depression-free today.

During the first handful of treatments, however, Armstrong was certain it was not working. The logistics of the trial were overwhelming — not eating for nearly 24 hours at a time, three days every week for nearly a month; hours of recovering from what she described as an exhaustion that felt like “swimming through peanut butter”; still somehow working part-time for a nonprofit; relying on her mother and stepfather to drive her to and from her appointments, and also help her hide the specifics of what she was doing from her girls.

“I didn’t think my kids needed to wrap their heads around this kind of experiment,” she said of Leta, who is now 15, and Marlo, who is nearly 10. “I didn’t want to burden them with the idea of their mother going to a clinic and being put under anesthesia 10 times. All I told them was that I was desperately trying to get better.”

Then one day she realized she was getting better. After the fifth treatment, on St. Patrick’s Day of 2017, Armstrong didn’t feel groggy as she had the other four times. The next day she showered, and put on makeup, and wore clean clothes without even thinking about any of those things, whereas for months those simple acts had been so exhausting she went for days without doing them. She called her mother and “had a regular, normal conversation about something or other” with the extended family. At bedtime that week, Leta said, “The tension in your face is gone.” Armstrong texted Mickey, writing, “I want to let you know that I feel like I lost a limb and got it back.”

It is dinnertime at the Armstrong-Ashdown household, and the shakshuka prepared by Pete Ashdown is delicious. He is a great cook, and she is no longer a vegan, and the two facts are not unrelated, as Armstrong and her girls moved in with the man she refers to on her blog as “Cowboy Hat” back in August.

Ashdown is a celebrity in his own right in Salt Lake. He founded XMission, the first internet service provider in the city. He’s also run for the Senate twice, in 2006 and 2012, and he and Armstrong have crossed paths professionally and politically a few times over the years, as both were vocal Democrats in a red state, whose lives revolved around the internet.

At a Halloween event “during the year of my depression,” Armstrong ran into Ashdown, talked for a while but declined when he later asked her out. “Something in the back of my brain thought, ‘I’m not ready for this,’” she remembers now. “I never called him back.”

Nearly a year later, after the treatments had worked, she was set up with him by a mutual friend, and this time “I was ready to accept what he was willing to give,” she says. “He’s the most generous person I have ever known other than my mother. He’s the greatest gift I have ever given to my kids.”

Marlo and Leta are in their usual seats for what feels every bit the family dinner (albeit missing Ashdown’s teenage son, who is spending this school night across town with Ashdown’s ex-wife.) Between forkfuls of “special toast” (Armstrong’s contribution to the meal, essentially toast with butter, which the girls love), Leta mentions that she has nearly finished her mother’s book. “You are such a great writer. I love the way you tell stories,” going on to cite so many specifics that it’s clear she’s read carefully indeed. Armstrong stops eating and looks like she’s about to cry. “You’ve never told me that before,” she manages, then deflects into a conversation about how Leta herself is a lovely writer, whose reading tastes usually trend more toward science fiction.

Although she carefully shielded the girls from her treatments, Armstrong very much wanted them to know the story before she told it to the rest of the world. The decision to be so very public about the experimental treatment was simple but for her reluctance to drag her children back into the spotlight with her — one of the reasons she had taken that break from blogging daily in the first place.

But it was as if she had no choice but to write a book, she says — because that is what she does, she processes out loud. And “the miraculous nature of what happened to me is too important, this research is too important for me not to spread the word.”

She particularly hopes to reach other single parents whose depression makes the weight of that role even heavier. That is why the book is full of repeated descriptions of herself as some version of “a full-time solo parent,” even though she knows that those who have made a hobby of trolling her over the years (this is the internet, there are many such people) will say she is feeling overly sorry for herself.

“They’ll say, ‘Heather thinks that she’s the first person to ever raise children alone.’ No, I don’t. But the reason I keep emphasizing it is that I want other parents to feel less alone. This is really, really hard. It’s hard when you do have a partner. When you’re juggling it by yourself, there is an aspect of it that is so relentless and unforgiving. Even now when I am stable, I am constantly feeling, ‘How am I going to do this, how am I going to get this done.’”

The first 10-subject trial was written up in the International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, in which the researchers concluded: “These findings demonstrate that high-dose propofol treatment is feasible and well tolerated by individuals with treatment-resistant depression who are otherwise healthy. Propofol may trigger rapid, durable antidepressant effects similar to electroconvulsive therapy but with fewer side effects. Controlled studies are warranted to further evaluate propofol’s antidepressant efficacy and mechanisms of action.”

That is another message Armstrong says she wants to spread — that this research exists and that with proper funding and attention (it now has its own Twitter page) could move on to its next step, which is a double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

“I was sitting on my porch the day after the fifth treatment, and I was watching my children zoom by on their scooters, finally able to take in the fullness of who they were and are and who I was as their mother, and to breathe in the sun and the light of life,” she remembers of her decision to write this book. “The change was so distinct — and I felt so grateful for having won the lottery of being a part of this treatment — that I [realized] I need to say something. I need to say something because this could save so many lives.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: