‘Oh, you’re the basketball player’: 30 years later, star player still has folks talking

In February 1991, David Strickland was an eighth-grade middle school basketball player at Forsyth Country Day, near Winston-Salem. Strickland, who would later become a superior court judge in Mecklenburg County, said he saw something on a cold Monday night that he never forgot.

He saw the best girls’ high school basketball player to come out of Charlotte have her best game.

“She was a couple years ahead of me,” Strickland said, “and we had heard a lot about her. There are few things in life you watch and it’s like, ‘There’s something special happening here.’ That’s what I saw that night.”

RANKING: Here are the best Charlotte high school girls’ basketball players in the past 40 years

Providence Day was playing at Forsyth Country Day, and earlier that day, the latest Sports Illustrated magazine had come out with USA Basketball’s Dream Team on its cover. Inside, there was an article about a high school phenom named Jason Kidd, talking about his recruitment. Next to it was a similar article about a 10th-grade girls’ star at Providence Day named Konecka Drakeford.

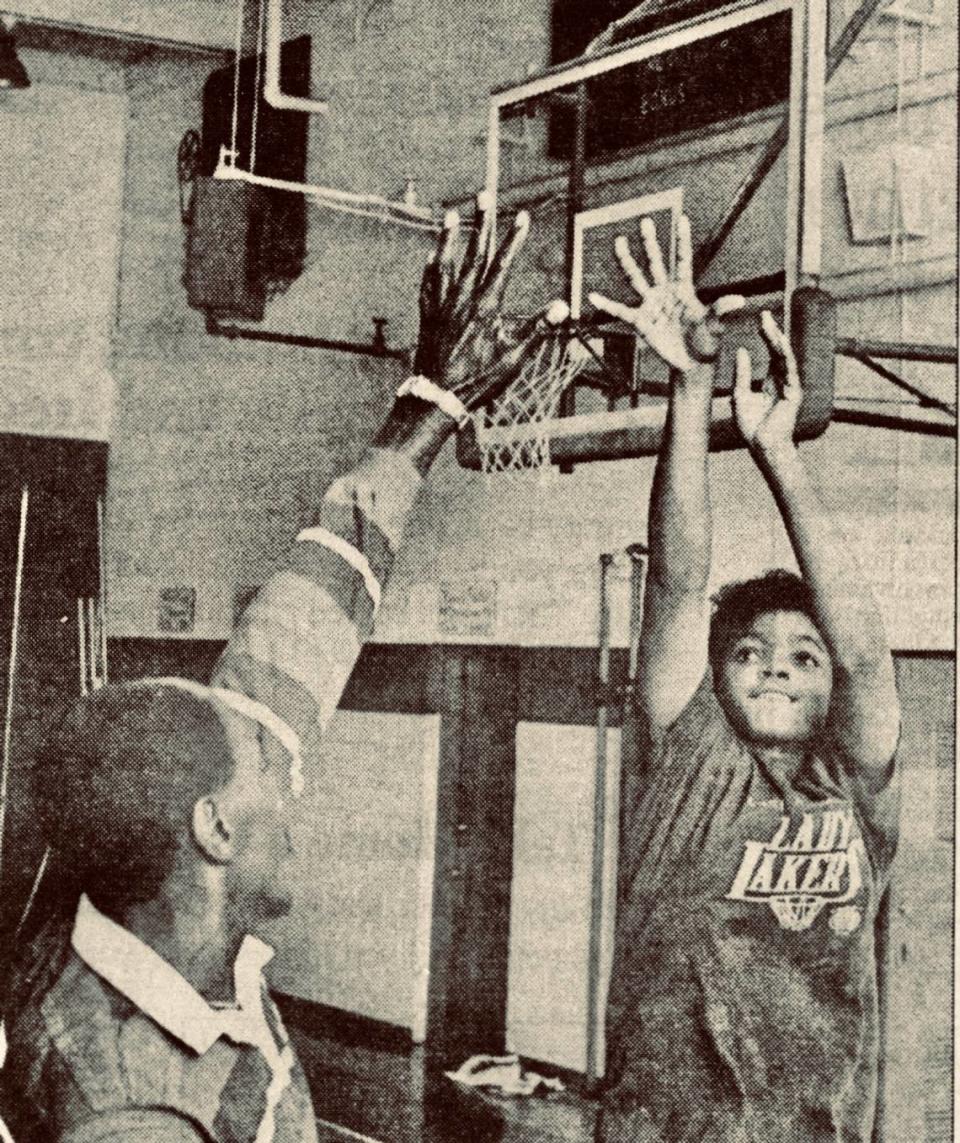

![9/2/95 2B: DRAKEFORD [UNPUBLISHED NOTES:] (5/8/94 PICKETT) Konecka Drakeford](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/VzFlqNv1IXFrpTqHgA_ZAQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTE0NDQ-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/charlotte_observer_mcclatchy_513/ca2da410380639f131f3e1446d5c06bc)

And it seemed like all of Forsyth Country Day was waiting to see her.

“We get off the bus,” former Providence Day coach Barbara Nelson said, “and all these students are standing out there, razzing her a little bit, and our team got close around her and we walked into the locker room. She said, ‘Coach, I’m fine.’”

Providence Day was down to seven players — five post players and two guards — because of injury and illness. Forsyth Country Day had two 6-foot-3 players signed to N.C. State to play volleyball.

Drakeford, a 5-10 wing, scored an N.C.-record 65 points that night, a mark that still stands. Her team won, 74-64.

“They were undefeated and we were undefeated,” Nelson said. “And we come out of the locker room. She’s exhausted. But all those kids who were giving her grief are now waiting with pens and Sports Illustrated magazines to ask her to autograph.

“We waited for 30 minutes for her to sign every one.”

Drakeford would go on to score more than 3,000 high school points, make a pair of All-American teams and win nearly every award imaginable. About 30 years later, after a long pro career overseas, Drakeford had started working in the foster care system. She was working a case when she ended up in Strickland’s courtroom, when he was then a district court judge.

“Usually, juvenile court is small and I have everybody stand up and introduce themselves,” Strickland said. “She said her name and I’m like, ‘It’s got to be the same one.’”

Strickland had Drakeford approach the bench. He covered his microphone and told her about the time he saw her play at Forsyth Country Day.

“We lost count of how many points she had,” Strickland said, remembering that game. “I mean, our girls’ teams were good back then. This wasn’t like scoring 63 now when someone wins 100-12. It was one of the greatest performances I’ve ever seen in any sport.

“It truly was.”

The tough school years

As good as she was, there were many days that Drakeford dreaded going to Providence Day. Before she arrived, in December 1989, there weren’t many Black students at any of Charlotte’s primary private schools: Charlotte Christian, Charlotte Latin, Charlotte Country Day and Providence Day.

Drakeford would become one of the first Black female athletes at any of them, according to her high school coach at the time.

And she actually tried to intentionally fail the entrance exam at Providence Day.

“I really cried,” said Drakeford, now 48. “I went over there for the entrance exam and I didn’t see anyone who looked like me except the janitorial staff. I felt out of place. It was just weird because all the people that looked like me were waiting on people who didn’t look like me.”

Before her ninth-grade year, Drakeford said her parents had moved out of the Myers Park zone and into West Mecklenburg’s, where legendary coach Becky McDonald already had a strong team. Adding a player like Drakeford, who had twice been named AAU national player of the year, while playing up in age, would make the Hawks the favorites — not just in Charlotte, but in North Carolina.

Drakeford said Myers Park’s coaches had followed her in junior high. They had seen her on ESPN after she scored 62 points during an eighth-grade game. And when she didn’t show up to high school at Myers Park, there were many questions. Eventually, she said, a call went in to Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools’ uptown office. Despite showing documents to prove the family had moved and resided in West Meck’s district, Drakeford was not allowed to play though she had enrolled and was attending the school, according to published media reports at the time.

So in December, at her parents’ urging, she found herself across town in southeast Charlotte, taking an entrance exam.

Drakeford qualified and got into school at Providence Day. On her first day there, in an advanced English class, the students were watching “To Kill A Mockingbird,” and a scene came up where the characters used the N-word several times.

“Everybody looks at me, and I’m sitting in the back of the room,” Drakeford said. “I’m like, ‘What are y’all looking at me for?’ It was hard.”

The early days were hard, she said, but they got a little better. Drakeford became close with teammates and her teammates’ friends. At lunch, Drakeford found a home sitting at what she called “the nerd table.” She slowly began to scratch out a social life, all while the Chargers’ student body was watching a wunderkind on the court who eventually averaged 29.3 points, 12 rebounds as a freshman and led Providence Day to a 27-1 record and the school’s first state girls’ basketball state title.

“I’m a very shy person,” Drakeford said, “and I don’t like attention. I didn’t like the attention I got from basketball. And this is the thing people don’t get about private schools. These kids have bonds ... (they) have grown up together. I just didn’t fit in.”

Drakeford said she would often go into the bathroom and cry during the school day. She would cry in the locker room when she thought it was empty. She just didn’t let her parents — Steven and Tonie — know how bad she was feeling. Or how often.

“I never let my parents see me cry,” said Drakeford, who has two younger sisters, “because I knew the sacrifices they were making (her father had taken a second job) for me to go there.”

Major on-court success and a break

On the court, though, Drakeford was a phenom.

She averaged 44 points and 17 rebounds as a sophomore and led her team back to the state finals. Drakeford scored 50 points in the final, but Charlotte Latin’s Elizabeth DuBose hit two free throws with six seconds left and Latin upset the Chargers, 63-62.

Drakeford won her second straight Observer Player of the Year award, repeated on the Associated Press all-state team and was named a first-team Parade All-American.

But that final loss hurt.

“I remember one game where I scored 20-something points, and (The Observer) wrote, ‘That was way off her average,’” Drakeford said. “To me, even though that’s more than what many normal people would probably score, I felt I let people down. Same when we lost in the state finals. That’s what your mind tells you. People paying money to see you and you don’t perform up to that level. I was 15. It was a lot to carry.”

Nelson, her high school coach, has often told the story that if Drakeford was going to walk around the neighborhood with her friends, her father, who passed away seven years ago, made sure that she was dribbling a ball with her left hand while she did it.

“He was doing the best job he could,” Nelson said, “and he pushed her hard. And she always seemed to respond and she would have moments where it was too much and I would step in. But she hated to lose. She was a tremendous competitor. And she was so skilled, and back then kids were not necessarily that skilled. Her dad was her trainer. Honestly, they were ahead of their time. It was unbelievable how much better she was than everybody else.”

That summer, in 1991, a recruiting expert suggested to Nelson that they register Drakeford for the USA Basketball team tryouts. Back then, there were not age group divisions. So among the 250 players Drakeford was working out with were Teresa Edwards and Cynthia Cooper, who would play on the 1991 Pan-Am Games team and later win the bronze medal at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona.

Drakeford made every cut until officials went from 25 players to 17, the final group that would eventually go to train in Colorado Springs.

“She was that close,” Nelson said. “This little 15-year-old kid out there and Ruthie Bolton is out there. Teresa Edwards is out there. That’s a statement. They would put the (players’ numbers on the board who had made it to the next round), and hers is still up there. You’re like, ‘Oh my God. She’s still in this.’ It was amazing.”

An unexpected year off and college

By the start of her junior season, after years of year-round basketball, major college recruiting attention and pressure, Drakeford was burned out. Everybody knew it.

Nelson and her parents hatched a plan for Drakeford to simply be a student her junior year. To not play. Only Drakeford couldn’t get herself to do it.

“They came up to me and said to not play and (to) focus on school,” she said. “I was like, ‘Nah, I’m gonna play.’”

So Providence Day went to a jamboree in Winston-Salem in the fall of 1991, and Drakeford was off on a fast break. She was getting close to dunking but always was high enough to slap the backboard after she shot. It was a move, at the time, that few high school girls could do.

As she gathered to jump, Drakeford noticed a player trying to chase her down from behind. She tried to adjust her body.

“The girl forced me to go one way and my body went another,” she said. “I heard a pop.”

Drakeford had torn three ligaments in her right knee. Doctors said recovery could take up to 14 months. And when the pain settled down, taking time off began to have some appeal.

“Nobody is going to get to critique me,” she said. “I can get rest and not worry about scoring 44 points per game. But once my dad attempted (to get a) fourth diagnosis — we saw four doctors — I was only out eight months.”

After surgery, Drakeford had physical therapy before, during and after school. She was back much earlier than expected, in just eight months. She missed her junior year but became the first three-time Associated Press all-state player from Mecklenburg County as a senior and returned to the Parade All-America team. She averaged 40.3 points and 13 rebounds, shot 64 percent from the field, and was invited to the Kodak girls’ high school All-American game, which was televised nationally on Prime Network.

College, out, and back again

Drakeford chose national power Virginia over North Carolina for college.

She was generally regarded as the best high school player in America in 1993. As a freshman at Virginia, Drakeford was averaging 16.2 points per game in her first two months. Then she broke a team rule, which eventually led to a transfer.

Debbie Ryan, then the Virginia coach, thought Drakeford could have led the Cavaliers to a national title.

“Had she stayed ... chances are that we could have been to a couple more Final Fours here,” Ryan told The Observer in 1998.

Said Drakeford: “That was when I was 18 and I choose not to talk about it. I feel like God has his plan.”

Drakeford transferred to Alabama, enrolling in August 1994. In two weeks, she broke her ankle in a pickup game and got homesick.

“Konecka was the kind of player who really needed the opportunity to play in order to keep focused,” then-Crimson Tide coach Rick Moody told The Observer in 1998. “Without it, she just decided that it wasn’t worth the wait here. I was very disappointed.”

To JC Smith and overseas

Drakeford came home and worked at Toys “R” Us during the 1994-95 season, just two years after finishing perhaps the best girls’ N.C. high school career of all time.

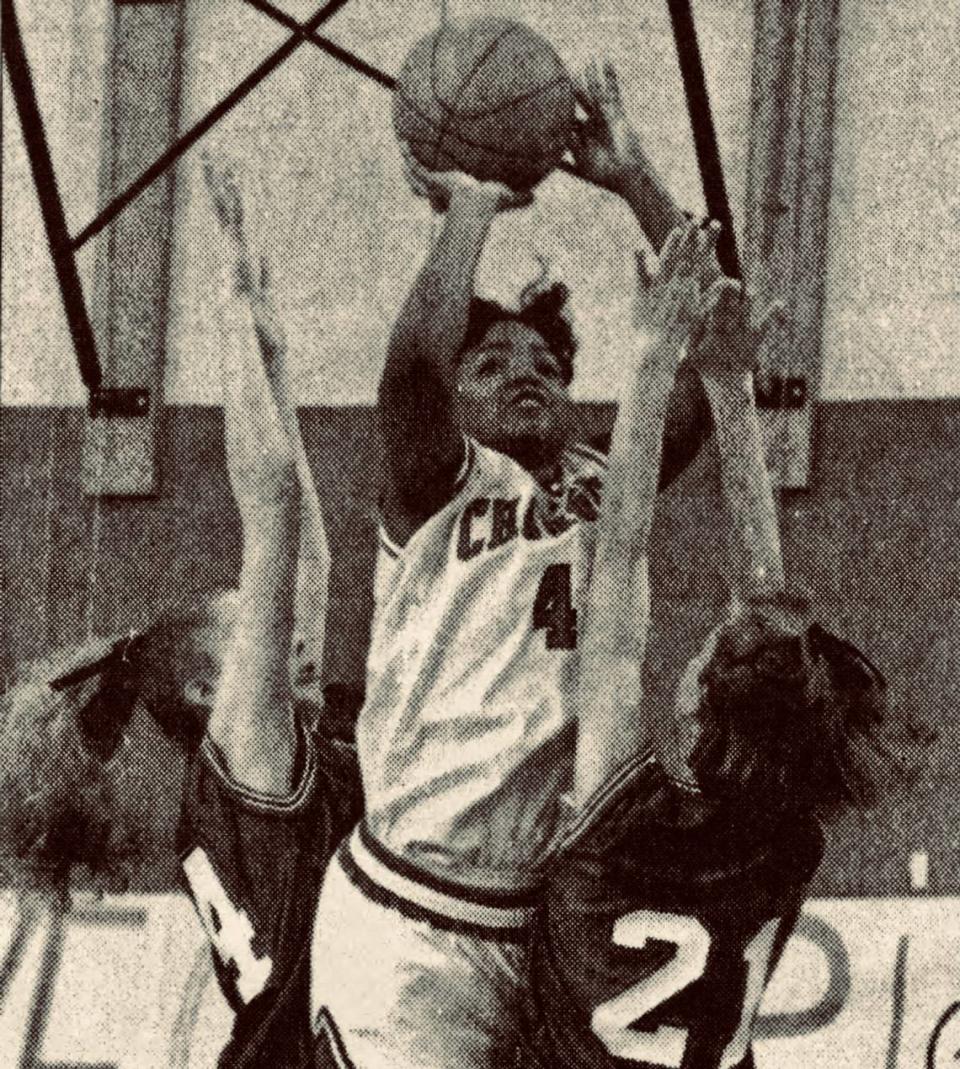

She enrolled at Johnson C. Smith, a small Division II school in Charlotte, in the 1995-96 school year but didn’t plan to play basketball. The Golden Bulls’ men’s coach, Steve Joyner, played a big role in getting her to come back, Drakeford said.

“She was a very highly talented young lady that was just trying to navigate her way through life,” said Joyner, who retired last month. “She was a bit confused and had mixed emotions. I tried to make things plain for her to see forward. And she became one of the best to ever play here.”

Drakeford averaged 22 points in her first year at Smith and 31.2 in her second, which led all of NCAA Division II in scoring. She had three games with more than 40 points and a career-best 59-point effort in the 97-98 season, when she was named Division II national player of the year.

Drakeford graduated early from J.C. Smith and didn’t come back for her last season of eligibility. She had gained some weight and was now an undersized post player instead of an explosive wing. She was invited to several WNBA workouts but was not drafted or signed. Drakeford eventually played 10 seasons in Israel, Sweden, Belgium and Syria. She once scored 67 in a game in Sweden, a new career high at any level.

In 2008, Drakeford put down the ball for good. She had a son, now 14, shortly after that.

“I’m living life as a normal person,” she said. “But it seems like no matter where I go, people are like, ‘Oh, you’re the basketball player.’”

She laughs.

“I work in Gaston County and when I started there five years ago, somebody said, ‘Hey, aren’t you Konecka Drakeford?’” she said. “People looked me and are like, ‘Who are you?’”

Leaving a legacy

Drakeford leaves a huge legacy of records and memories. But of all her accomplishments, there are a few that stand out:

? Her 3,119 points rank fourth in state history, among public or private players. The three girls in front of her played four years; Drakeford, three (and she missed nearly half her freshman year). “She would have 4,000 easy if she played that junior year,” Nelson said.

? The N.C. public school record for points in a season is 1,159, set by Clinton’s Mikayla Boykin in 2017. Drakeford scored 1,242 as a senior and 1,364 as a sophomore. The next-highest Mecklenburg County single-year total is 936, from North Mecklenburg All-American Andrea Stinson in 1987. And Drakeford’s 820 points as a freshman is also a state public or private school record.

? Her 44 points per game average as a sophomore is another state record, followed by her 40.3 average in her senior year. Fayetteville Terry Sanford’s Shea Ralph is third. Ralph, now the women’s head coach at Vanderbilt, averaged 39.1 points per game in 1995.

And there are many more, like her 37.8 career scoring average, more than four points higher than any other N.C. girls’ player.

“I didn’t cheat the game,” Drakeford said. “I feel like every time I went on the court, whether I had a good game or a bad game, I always left it on the court. And that’s how I would like to be known, as somebody who didn’t cheat the game. I don’t think a lot of people can say that.”