Rob Oller: Jesse Owens was Hilltop hero to Westside neighbors in 1930s Columbus

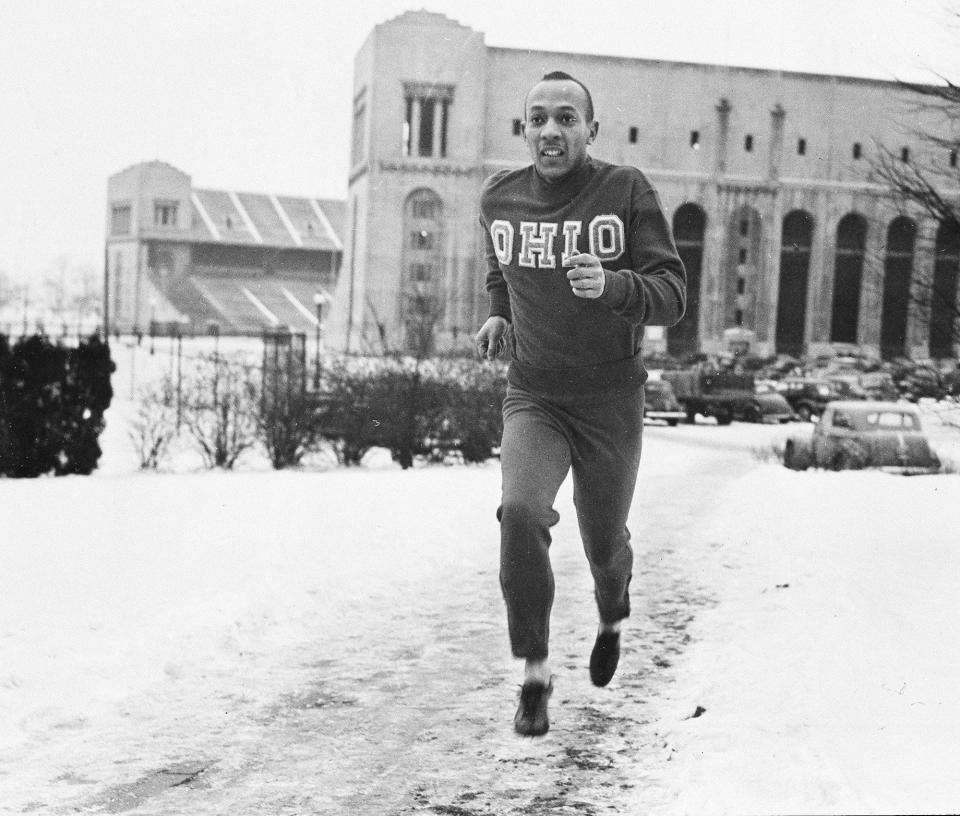

The 200 block of S. Oakley Avenue on the Hilltop stretches about 210 meters, which was right in Jesse Owens’ wheelhouse. But the world’s fastest human never sprinted that short distance between Broad Street and Sullivant Avenue. He walked it.

Owens lived at 292 S. Oakley while attending Ohio State — Black students were not allowed to live in campus dorms — and often went up and down his street escorting kids to a vacant neighborhood lot to play sports.

Earl Potts was one of those kids. The Hilltop resident, who passed away in 2021, once recalled how Owens enjoyed getting children involved in athletics.

“He’d gather the young kids and say, ‘Let’s walk over to the ball field,’ ” Potts said a decade ago during an interview available on YouTube.

Upon arriving at the diamond, all eyes turned to Owens.

“There used to be softball games between married men and single men … and my uncles used to tell the story of Jesse playing ball,” Potts said. “They’d let him hit and just run the bases without tagging him out because they liked to see how he ran. His stride was so beautiful.”

Jesse Owens' life on the Hilltop in the 1930s

Owens was called a lot of things in the early-to-mid-1930s, not all of them complimentary. He was the Buckeye Bullet and the Pied Piper of the Hilltop, but he also heard more than one racial epithet.

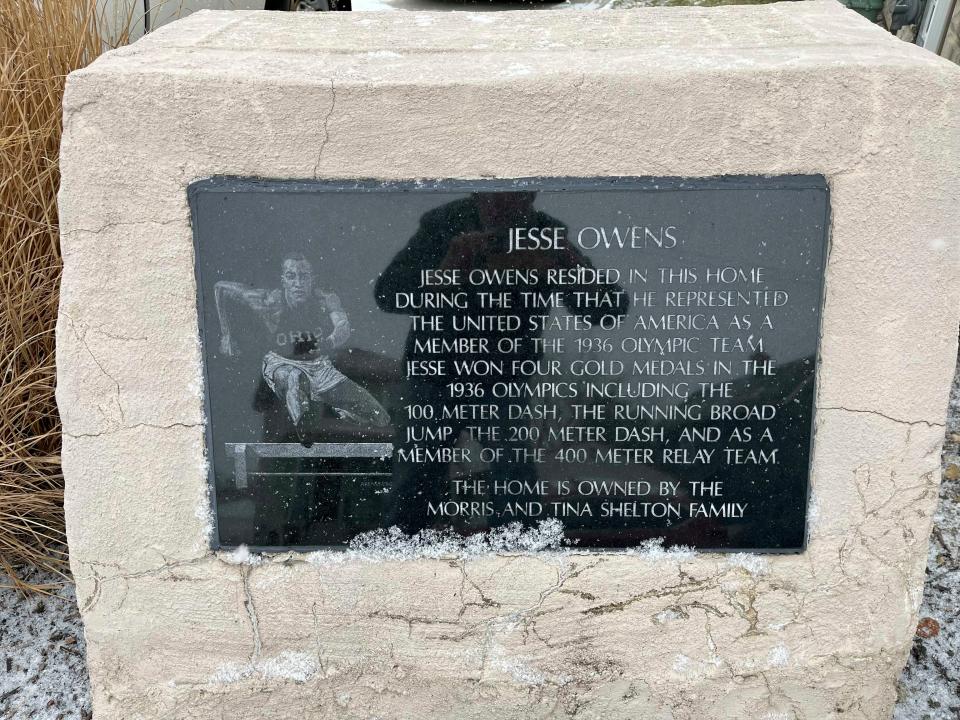

Despite breaking racial barriers during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, where he won four gold medals to cripple Adolf Hitler’s claims of Aryan superiority, prejudice and bigotry reappeared when Owens returned to the United States. What he experienced after Berlin was no different than what came before — exclusion based on color.

Arriving at Ohio State from Cleveland, Owens had to live off-campus with other Black athletes.

“This was a common practice at Midwest (predominantly white) universities,” said F. Erik Brooks, who co-authored an Owens biography with Kevin M. Jones. “But it was better than what African-Americans were getting in the South.”

A low bar, indeed. Even at Ohio State, Owens could only order carry-out or eat at “Blacks-only” restaurants. He was forced to stay at segregated hotels during travel.

At least the Hilltop offered some respite from discrimination, though Black residents still were confined to a small area that ran east-west from Clarendon Avenue to Wayne Avenue and north-south from Palmetto Street to Sullivant.

The Hilltop was segregated by practice, if not law. Real estate agents, developers and civic organizations helped redline portions of the community.

“The unwritten law was they wouldn’t move in any Black person who wanted to live in a white community,” said Clenzo Fox, a retired lawyer who grew up on South Oakley. “They wouldn’t loan the money out. My mom wanted to move but couldn't get the money from the bank, where she had been banking for over 20 years.”

Owens lived between Logan Street and Ray Street, and today the residence includes a marble marker listing his athletic accomplishments, including winning gold in the 100- and 200-meter dashes as well as the 400-meter relay and long jump in Berlin.

But upon returning to the Hilltop, Owens quickly came to a realization.

“After I came home from the 1936 Olympics with my four medals, it became increasingly apparent that everyone was going to slap me on the back, want to shake my hand or have me up to their suite,” Owens said. “But no one was going to offer me a job.”

Eventually, Owens returned to Cleveland, where he found work as a playground director working with disadvantaged youth. His life had come full circle, given he was the son of a poor sharecropper who moved his family north for better job opportunities.

Born James Cleveland Owens in Oakville, Alabama, young J.C. was 9 when he received a name change upon moving to Cleveland. An elementary school teacher struggled with Owens' accent and mistakenly recorded J.C. as Jesse. The name stuck. A decade later the name became known internationally when Owens, as a high school senior at Cleveland East Tech, set a world record in the 220-yard dash (20.7 seconds) and tied the world mark of 9.4 in the 100-yard dash.

“I never met Jesse personally, but as we grew up on the Hilltop, we all knew of his exploits,” Fox said. “He absolutely was a role model, and anyone who grew up around the Hilltop, including my own community, knew that Jesse was quite a person.”

Fox, 93, likes to brag about Owens almost as much as he loves to boast about how close-knit the families were that called the Hilltop home.

“We took pride in it. Such a special place to live,” he said.

Caring and compassionate residents helped make it special, Owens being the most famous among them.

“Jesse was one of the best people I knew personally,” said former Ohio State track coach Frank Zubovich, who ran for the Buckeyes under Larry Snyder, who was also Owens' coach at OSU. “Whenever he was in town, he would stop by the office to say hello. He would come to practice and … walk over and talk to the athletes.”

Walk. Run. It didn’t matter. The Pied Piper of the Hilltop always led the way.

This story is part of the Dispatch's Mobile Newsroom initiative. Visit our reporters at the Columbus Metropolitan Library's Hilltop branch library and read their work at dispatch.com/mobilenewsroom, where you also can sign up for The Mobile Newsroom newsletter.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Jesse Owens lived on Hilltop, OSU dorms off-limits to Black students