If Donald Trump Doesn’t Own the Rights to ‘Nasty Woman,’ Who Does?

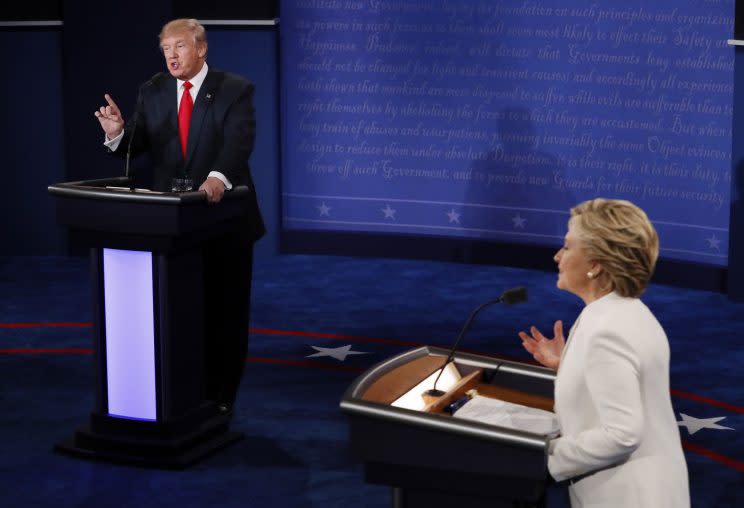

During the third and final presidential debate of the 2016 election season, then presidential candidate Donald Trump interrupted Hillary Clinton, calling her “such a nasty woman.”

And thus, the “nasty woman” microeconomy was born.

Social media fed on the interjection, launching nasty woman memes, mugs, T-shirts, notebooks, and other merchandising opportunities. The phrase was stamped on feminist uniforms, displayed for the world to see at January’s Women’s March.

Fashion designers have also claimed the phrase as their own. It was most recently seen on British designer Ashish’s runway on Feb. 20 amidst a largely anti-Trump collection. A sequined vest was emblazoned with the phrase.

While Ashish is using his platform to fight Trump, both on and off the runway (and across the Atlantic), a separate battle is being fought for the rights to the term “nasty woman” itself.

After the October presidential debate, dozens of parties filed trademarks with the U.S. Patent and Trademark office for the sole rights to “nasty woman.” The first person to file such a trademark was Mike Lin, an entrepreneur and serial trademark filer (disclosure: Lin previously worked at Yahoo). Lin filed his trademark for “nasty woman” with the USPTO on Oct. 20, just one day after the debate.

“It seemed liked a cool phrase, and there’s the whole Janet Jackson ‘Nasty’ thing,” Lin told Yahoo Style. “I like to do mashups here and there.” In this case, Lin said, he plans on fusing beverage brand Nestea, the rapper Nas, and “nasty woman” as one.

It wouldn’t be the first pop culture pun Lin has tried to market as his own. He also applied for the trademark “Poison Ivy Park,” a mashup between the comic villain Poison Ivy and Beyoncé’s athleisure line, though he received a cease-and-desist order from Beyoncé’s team. Lin told Yahoo Style he has spent roughly $35,000 to file more than 70 other trademarks in the past year, including the rights to phrases like “Black Mamba” (disputed by Kobe Bryant) and “Mortimer Mouse” (disputed by Disney).

On Feb. 8, the USPTO refused Lin’s registration, saying “The applied-for mark merely conveys an informational social, political, religious, or similar kind of message; it does not function as a trademark or service mark to indicate the source of applicant’s goods and/or services and to identify and distinguish them from others.” Translation: The message exists in the public sphere, and Lin can’t claim it as his own.

Lin said he plans on responding to the refusal by providing evidence that his trademark is original and necessary to the creation of his brand, standard procedure for someone whose registration is initially denied. Try as he might, Susan Scafidi, founder of the Fashion Law Institute, thinks it’s remarkably difficult to earn the exclusive rights to a popular catchphrase like “nasty woman.”

“A trademark is expected to appear as the brand name on every label, or as the logo on every item, not just as a design on the front of one T-shirt or coffee mug,” Scafidi explains in an email to Yahoo Style. “It would be possible for someone to create a ‘nasty woman’ product line and register the trademark — unless the U.S. Trademark Office believed there would be consumer confusion with, for example, the ‘Nasty Gal’ clothing brand — but the bottom line is that the [USPTO] is likely to be skeptical.”

Scafidi goes on to explain that there is an important distinction between a trademark and a product, which may be one reason “why Donald Trump, back when he was merely a reality TV star, sought registration for ‘You’re fired!’ in multiple product categories but doesn’t actually own the phrase in any category today.”

Lin may have been the first to file for the “nasty woman” trademark, but he was not the only one. Amanda Brinkman, creative and operations director of the artist collective Pelican Bomb, created “nasty woman” T-shirts with a heart-shaped design. Brinkman told Yahoo Style she only planned on making a handful of the shirts, but then Katy Perry wore one to a Hillary Clinton rally and the merch went viral. Soon after, Brinkman spent more than $3,000 to file and monitor a trademark application on her “nasty woman” design, not the phrase itself.

Brinkman said she has raised over $125,000 for Planned Parenthood through her shirt sales since October and that the reason she filed for the trademark has a lot to do with supporting the women’s health care organization.

“I’ve been trying to get a mark for my design because a lot of people tried to use it on other T-shirt sites pretending to be me, when I give 50 percent of my sales to Planned Parenthood and the others don’t. They weren’t donating, and that troubled me.”

Filing a trademark for the phrase or a design means discouraging copycats from cutting into the original’s sales. While cases of trademark and copyright infringement in fashion are numerous, they’re often hard-fought, costly battles that are not easily won. Natalie Arbaugh, one of the chief litigators who helped Tory Burch win $41.2 million in a 2015 trademark infringement lawsuit, tells Yahoo Style that a case that goes to trial can easily cost more than $1.5 million.

Of course, that assumes someone like Lin is granted the rights to “nasty woman” in the first place; in fact, though numerous parties have filed for the trademark rights to the popular phrase, the USPTO has yet to grant anyone’s request. Arbaugh thinks Lin’s is a tough case to make, since he’s trying to trademark a political slogan, not a “source identifier,” something that is essential to a brand or product (think: the Ralph Lauren polo player or the Abercrombie & Fitch moose).

“In clothing, you have to show that [the trademark] is not merely ornamental on the clothing. It can’t just be decorative. … It should come to associate the item with the maker of the trademark,” Arbaugh says. “You don’t just get to trademark anything you like.”

Related: Anna Wintour Seen Wearing This Political Accessory at the Brock Collection Show

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.