Frank Marino on why solid-state amps make the best pedal platforms and starting his own stompbox company

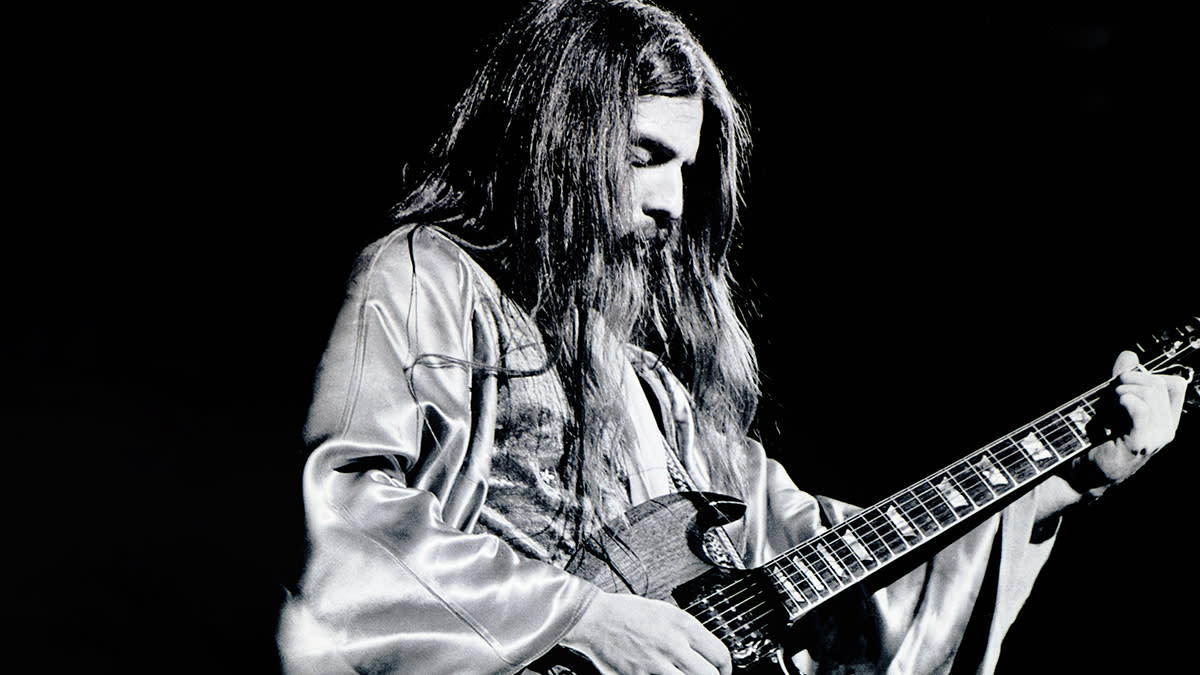

As one of the fiercest guitarists of the immediate post-Hendrix generation, Canadian Frank Marino blazed a trail as a shredding soloist, master of riffage, and one of the game’s earliest hot-rodders. If you listened to any of his output with Mahogany Rush, you’re very aware of his prowess.

But to see Marino live was to see him in his true element: backed by any number of solid-state amps and a six-foot-long pedalboard at his feet, filled with stompboxes of his own creation – in an era when oodles of pedals weren’t a thing.

While most guitarists plugged into a Plexi or a Twin – which, as we’ll learn, aren’t so different – and dimed them, Marino created his own Frankenstein tone.

In the years to follow he’d proudly become known as a player’s player, but in recent years, undisclosed health issues have left him unable to tour. The word was that he’d all but retired – but that’s not entirely true. Lately he’s been crafting pedals by hand, one by one, with the intent of gifting his coveted tone to those who seek it via his new brand, Frank Marino Audio.

“I think the main problem is that the designers of pedals and gear aren’t actually players,” Marino tells Guitar World. “The exception is a guy like Tom Scholz from Boston. There’s another guy who played in a band and had a degree in electronics engineering.

“I would expect he would know what he was doing. But I think most guys designing pedals don't play in bands or go on tour – not all, but most. Most of the guys on tour don’t design pedals. In my case, I do both. So I’ve got a little bit of an advantage there.”

The idea is to make pedals offering the sounds of his ‘70s boards, that look sharp now and will still be cool in a few years. He’s currently offering three products for sale: the Juggernaut fuzz, Dragonfly overdrive and Maxoom boost.

He’s also working on a clean sustain and an envelope filter – but they’re prototypes that may never come out. Beyond that, tales of his official retirement are overstated. “I’m trying to fix my hand,” Marino says. “If I can, it’s very likely I’ll do a gig.

“I love to play – I could probably play enough to do a video demonstration of some of the pedal stuff – but I can’t play like me. There are things I can’t do because my finger hurts too much. I’d rather wait until it’s totally fixed.”

You’ve been dealing with some health issues. What brought you to this point?

“I’ve got a little bit of a health problem. I don’t want to go into detail about it, but it stopped me from touring. I’m dealing with it, so hopefully it goes away. It’s not impossible that it just goes away. That’s one thing – but when I started making the pedals I damaged my left hand.

“I’m making these pedals by hand. I was grinding, pressing and everything by holding stuff in my left hand. I damaged a nerve in the index finger, which stopped me from playing guitar. I’m seeing a specialist for that.”

Will you be able to play guitar again?

“At first I stopped touring, but I could still play guitar. Now, it’s not that I can’t play guitar; there are things I can’t do because I can’t stretch. They assure me it will clear up if I do what I’m supposed to do. I might have to have an operation, but I can get back to normal. So I’ve got those two health problems to deal with.”

After playing guitar for your entire life, that must be quite a shock to the system.

“It has been. I’ve been playing nonstop for 55 years, and now suddenly I’ve got to be careful about how I do it because it hurts.”

And you wouldn’t want to get into any bad habits either, trying to compensate.

“Exactly. I even thought about turning it around and learning to play left-handed! I did seriously think about it. But then my wife said, ‘Look, go for the operation.’ I was having all these tests and stuff to see what the hell I damaged; I really damaged something in my finger.”

Your pedals emulate your quintessential sound and tone – was that the idea from the start?

“I’ve been doing it for a long, long time. I thought, ‘Would it be cool to take the pedals I designed and used for so many years and let other people have them?’ And somebody said to me, ‘That’s unheard of!’

I basically made my pedalboard make the sounds, and the transistor amp amplified them cleanly

“Most guys that play are very guarded about what they do. But I thought, ‘No – it would be cool to let kids have the same sound,’ because I happen to think I have a pretty good sound. It took me years to get it, so I decided to let other people have it too.”

What were the nuts and bolts that made up that sound?

“When I started in the ‘70s there were really great amplifiers, but no really great preamps. You had your Fender Twin and a couple of others that came later; you had basically Fender and Marshall.

“I put together this gigantic pedalboard and the board became the preamp. Then I got a transistor amp because it was clean. It was an Acoustic 270. I basically made my pedalboard make the sounds, and the transistor amp amplified them cleanly.

“So, throughout the entire ‘70s I was using a transistor amplifier. People don’t realize that; they think I was using a Marshall or something because of the tone. But the sound was coming from the pedals.

“And because you couldn’t buy many pedals, I decided to learn how to modify what was available to make it sound how I liked.”

What did that process look like?

“At first, I experimented, not knowing what I was doing – changing parts and luckily getting a difference. Then I started taking courses, reading books about it, and trying different things on pedalboards. That’s how I developed the sound.”

Your ‘board must have looked different from the ones we have today.

“It was gigantic – it was six feet long! Then I started building amplifiers, and putting the stuff from the pedals into the amplifiers. Then I was at the point where my amps did a lot of the work, and I had very few pedals left.

“I did this thing where I put all the boards in one case, so everything’s small, you know? But then I thought, ‘What if I took those out, put them in different cases, made them look good and gave them nice boxes?

“They take me a long time to do. A guy who orders one isn’t gonna get it tomorrow; it takes quite a bit of work.”

Hot-rodding gear only became commonplace in the ‘80s, so you were a pioneer.

Tony Iommi saw it was a transistor amp and basically, he refused, not realizing it worked. The bottom line was that it worked

“Right! And now, you have websites based on doing it yourself. There’s a DIY community, and they have YouTube – which, of course, we didn’t have. If you wanted DIY in those days, you had to run by someone’s place to ask questions or go to a library and figure something out.

“Today you have a lot of help from a lot of places. But the downside of that is there’s only so many ways you can build the mousetrap. Everyone’s trying to build a better mousetrap. To that end, despite how cool many pedals look, there’s a ton of redundancies.

“A fuzz is a fuzz – a fuzz is really just an overdrive, and it’s the same thing with distortion. And with amps, too. Once you know what’s going on inside, the mystery of why one sounds a certain way is gone.

“The mystery and the magic go away, and you realize that a Marshall Plexi is really a Fender Twin with the tone stack moved to the end of the preamp. It’s just a modified version of the Fender Twin with slightly different tubes.

“You’ve got the same thing with pedals. You can make fuzzes and overdrives in three or four ways. It comes down to a Jim Dunlop Fuzz Face, an EHX Big Muff and maybe an Ibanez Tube Screamer.

“When you look at the schematics, you see all the similarities except for a couple of different resistors here or capacitors there, which make them sound different.”

How do you battle those redundancies?

“I thought, ‘Everyone’s always talking about NOS,’ which is new old stock. I thought, ‘I’ve never been a purist about trying to use the oldest stuff available – there’s something to be gained from modern equipment but using older ideas.’

“So my pedals are based on very old ideas, like, ‘How does the original mousetrap work, but made with better parts and better care?’”

Many independent companies owned by artists end up partnering with larger companies. Is that something you’d consider down the line?

“There’s a lot of guys who have pedal lines, but they’re not designing them themselves. So if a company came along and said, ‘Can we put your name on our pedals?’ I don’t want to do that.

People like the compression. But it’s not so much from the tube as it is from the transformers. That’s the magic of a tube amplifier

“If these pedals were made any differently, or made by machines, there’s no way they’d sound the same. So I’d be selling a pedal with my name on it, but it wouldn’t be the same sound that I have on my ’board, which is what I’m trying to do.”

Going back to your earlier point about how people assumed you were using tube amps, many people are enchanted by the idea of tubes. But there’s an argument that solid-state amps are better pedal platforms.

“It’s definitely a better platform for pedals. I proved that throughout the ‘70s when everyone thought I was using tubes. I did a gig once with Black Sabbath, and Tony Iommi, of course, played through tubes.

“For some reason, they were having a really bad problem with grounding, and the crowd was sitting there listening to this huge noise. I walked up to Tony and said, ‘Why don’t you just use my amp? It’s still sitting there, plugged in.’

“He saw it was a transistor amp and basically, he refused. He said, ‘No, I’m not going to use that,’ not realizing it worked. The bottom line was that it worked.”

Why do you think people romanticize tube amps so much?

There are some companies that have some pretty good stuff that’s relatively inexpensive

“They like the compression you can get. But it’s not so much from the tube as it is from the fact that, by definition, tube amplifiers have transformers on the output. So they’re playing through transformers. That’s the magic of a tube amplifier.”

You’re proving there’s magic in solid-state amps, too.

“I’m building three new pedals and using some of the old technology, but I’m using some of the new ideas about how to put things together. This is just taking what’s already been done a million times and putting it together in such a way that this sound becomes available to a lot of people.”

It can be hard to know how to sift through all the options out there. What’s your best advice?

“Generally, the boutique stuff is going to be better than the regular stuff. The unfortunate thing about that, and the same thing with my stuff, is that it’s a little more expensive.

“The price doesn’t really reflect the pedal; it reflects the fact that somebody asked me to build them a pedal. I’m putting 20 hours into building that pedal.”

“But there are some companies that have some pretty good stuff that’s relatively inexpensive. What I would tell anybody is they try it – you’ll know in the first five minutes if you like it or not.”

For more info, head to Frank Marino Audio.