Vinyl pressing plants on surging demand, keeping it local, and whether coloured vinyl really does sound worse

A quickfire question for you: how many vinyl pressing plants does Australia have?

If you’ve just answered “zero”, having soundly assumed that the Land Down Under might exclusively import records from elsewhere, as it does cars, then I’m afraid to say you are incorrect. But don’t worry, you aren’t alone: that was my hesitant guess too when asked by a vinyl-loving family member during a recent visit to see me (and probably more so some record stores) in Melbourne.

If your answer was “three”, give yourself a big fat full point to redeem at the next pub quiz whereby you mark your own sheet… presuming you didn’t Google it, you big cheat. (Or half a point if it was “two”, seeing as the third plant only began operating less than two years ago. Nul points for anything else… sorry.)

So, in a country whose population is a third of the UK's population and which has just two IMAX cinemas, three vinyl pressing plants exist – Zenith Records (Melbourne) is getting on for 20 years old, while Program Records (also Melbourne) and Suitcase Records (Brisbane) began pressing four and two years ago respectively. For the, er, record, the UK doesn’t have many more.

So what’s behind the resurgence (if not to keep up with the demand for Taylor Swift wax!) and what does local access mean for artists? In celebration of Record Store Day and What Hi-Fi?’s Vinyl Week, I spoke to the co-owners of each Melbourne plant, Zenith’s Paul Rigby and Program’s Steve Lynch, to find out...

An unlikely resurgence

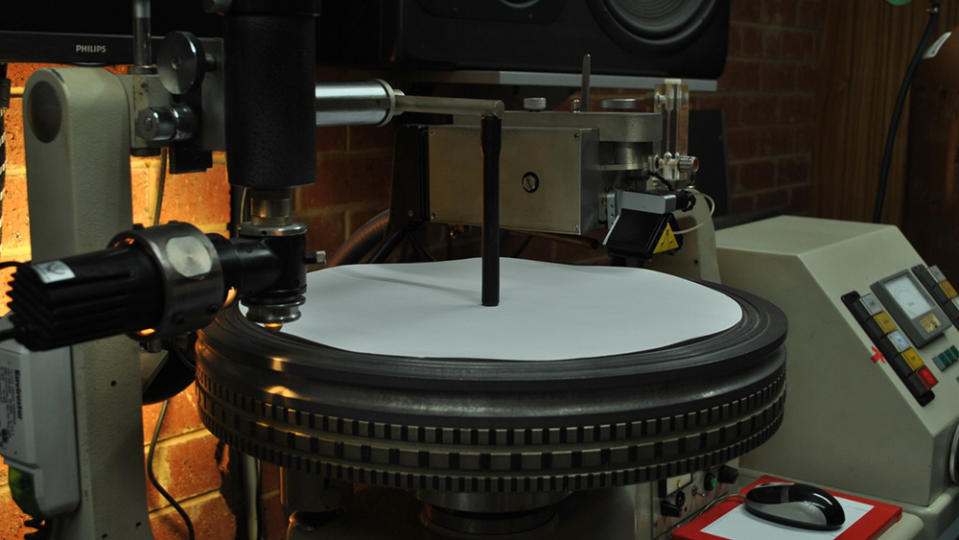

In the mid-’90s, a fella called Nick Philips of Melbourne-renowned garage-rock band The Breadmakers, saved Australia’s – actually, the whole Southern Hemisphere’s – only vinyl pressing plant at the time from the scrap heap in Sydney, and relocated it 500 miles down to Melbourne. Philips told Vice that it “singlehandedly saved vinyl record manufacturing in Australia”, and it seems they had a ball for over a decade, pressing thousands of records, reviving direct-to-acetate recording, and hosting Sonic Youth and The White Stripes. But Philips sold up in 2005, and in came Zenith Records to build on the barebones of what was the Corduroy Records plant.

Paul Rigby was in the CD and packaging business at that time but had forged an alliance with a French record manufacturer and witnessed quite the increased growth in vinyl demand from 2008 onwards. After a few years of his business partner running operations low-key, they together decided that the local market demand required improved market responsiveness, quality and output. Now, Zenith Records does the job lot.

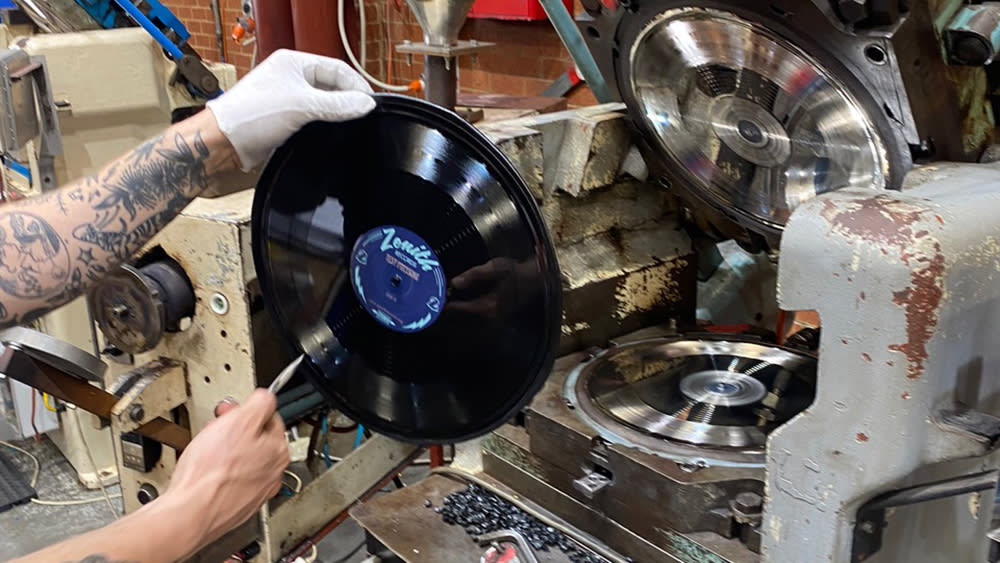

“In 2013 we set up operation in our current site in Brunswick East [20km south of the Cordoroy plant] and haven’t looked back,” says Rigby. “We now occupy four sites carrying lacquer cutting, galvanic plating, pressing, packing, sleeve glueing and paper inner sleeve glueing. We also have a dedicated engineering machine shop employing two CNC programmer operators designing and making innovative tooling, spare parts and associated machinery for the global vinyl pressing industry.”

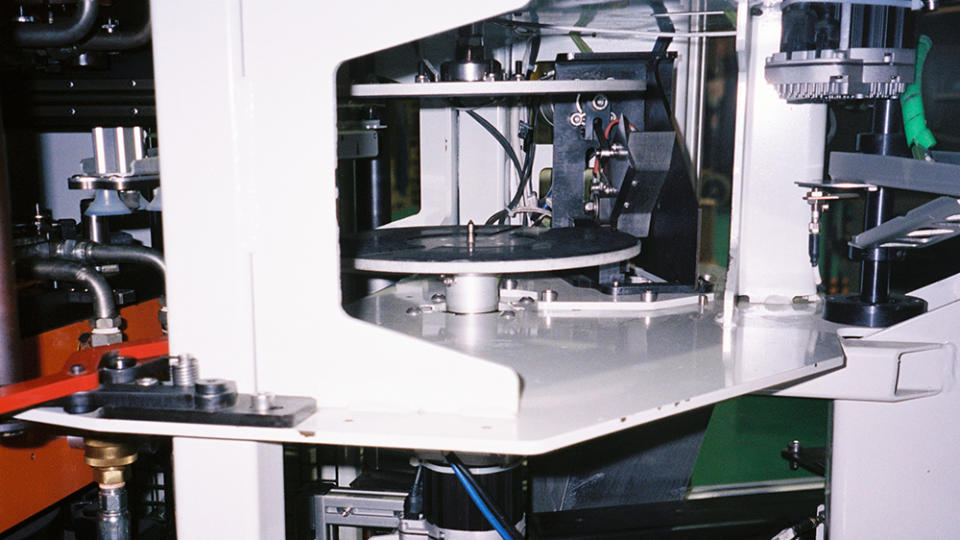

It rode solo for over a decade, and then Program Records came onto the scene in 2020, emerging, Steve Lynch tells me, from discussions around the difficulty local bands had in getting their albums pressed in time for release dates, and the considerable wait times at international plants. What a year to start up in the most locked-down city in the world! But Lynch notes that up until the late 2010s there were not many options for purchasing equipment to press records: “It was very difficult to source second-hand machinery so the only avenue to purchase were the new fledgling press manufacturers. Australia isn’t big enough to have the multitude of presses that we see in North America and Europe but the music scene is strong so there was an opportunity to set up with the new availability of equipment.”

When its two WarmTone presses from Canada manufacturer Viryl Technology arrived in 2020, but without the Virlytech technicians to assist in their installation due to the international travel ban, Program Records had to improvise. “Program’s technician Luke Marinovich and I would come into the warehouse in the early hours of the morning to Zoom-call Viryltech and set these up ourselves with their instructions!” remembers Lynch.

The pandemic was a blessing to the industry in some ways, though. Both Rigby and Lynch spoke about the surge in demand for vinyl pressing, the consequential overseas pressing plants' backlogs and substantial delays, and how, as a result of that, extra business came their way. “It meant that customers’ deadlines weren’t blown out to over 12 months, which is what was happening in the US and Europe,” says Rigby. “And often we found ourselves manufacturing export orders that would have otherwise been manufactured offshore.”

And there’s plenty of business to go around, it seems, despite the number of vinyl pressing plants in the country effectively tripling in the past four years. That’s not wholly surprising when you consider that in the past nine years the number of vinyl records sold has grown by 275 per cent, from 315,000 (2015) to 1,184,000 (2023), according to Statista and Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) figures. That trumps the UK’s 180 per cent growth during that same period and isn’t far off the US’s 300 per cent growth.

“[The competition has] helped us share the load of local and international demand and relieve pressure on just one local plant,” says Rigby. “It has meant that there are alternatives in procuring vinyl locally.

“Our position has always been: if competition means more orders will be placed for locally pressed vinyl records rather than these orders going overseas, then it's a good thing.”

Keeping it local

The two plants press records for both local and international artists and labels, though the local scene seems close to both of their hearts. “We love being able to press records from our local scene; there is something extra special about pressing records for bands/people you know,” says Lynch, who also acknowledges that choosing a local pressing plant “supports local jobs, fosters a sense of community, and helps build a robust ecosystem for music creation in Australia”. His favourite recent record? Program’s pressing of The Map And The Territory by Aussie post-punkers Exek.

Rigby and Lynch recognise several benefits of staying local for the artists too. “Local plants offer faster turnaround times,” says Lynch. “Artists and labels are also able to come and visit us when we have a test pressing or their records ready for them. This means they can get their records to the listener and onto store shelves more quickly as the record stays in Australia.

“Staying local also allows artists and labels to have more direct oversight and control over the production process. They can visit the pressing plant and communicate face-to-face with us.”

Paul Rigby, whose plant, Zenith, mostly presses records for Australian artists, agrees that manufacturing locally is cheaper, faster and gives artists greater access, plus it also helps with special events. “Occasionally we may be under deadline that means that part of the order needs to be ready ahead of the whole order and we have the flexibility to have customers come by and grab 50 or so units for a launch or a pre release event, without having to factor global shipping, which almost always requires completion of the full order.”

And then there’s the ecological benefits. Rigby tells me that recently representatives from all three pressing plants in the country, alongside domestic record labels, distributors, retailers and artists, attended an inaugural roundtable event for the Music Product Stewardship Alliance (MPSA) to discuss the environmental impact of all aspects of vinyl record production and logistics.

“Interestingly enough,” he says, “the major environmental impact was importation of internationally pressed product and the most sustainable way forward was to increase more local production, where possible.”

Steve Lynch reiterates this: “By pressing locally, artists and labels can reduce the carbon footprint associated with their music releases and support more sustainable practices. It also reduces the possibility of damage in transit as we are about five kilometres from the major distribution centres in the city.”

Rigby admits that keeping it local might not make sense when a local artist’s release has a larger market in Europe or the US, as having the whole order manufactured offshore and the smaller local component shipped back could then be preferable. But there’s no denying that the availability of local pressers is a boon, and perhaps even an enabler, in many cases – particularly for smaller or grassroots artists after shorter runs of hundreds or thousands, as opposed to tens or hundreds of thousands.

Pressing process: in-house vs outsourcing

Zenith and Program aren’t just squirrelling away to service (mostly) Australia without ties to the international industry, mind you. The plants are pretty different beasts – Zenith is a fully integrated facility that does everything from cutting music onto lacquer to creating the metal ‘stampers’ used on the pressing machines, to the pressing itself, while Program presses after outsourcing the cutting to Bristol and Berlin, and the stamping to Sheffield.

Zenith’s in-house operation is the more uncommon. Program’s Lynch acknowledges how it requires significant investment and expertise – “mastery would take years!” – and that its overseas suppliers excel in their craft, saving the company time and resources.

This pressing plant model of using third-party stampers or having metalwork supplied by customers is adopted by many plants in the US and Europe. Indeed, Rigby acknowledges that some discerning customers may prefer to supply their own metalwork and/or have their lacquers cut at independent cutting houses around the world, but says that Zenith’s model puts it in a position to control every aspect of the process, from start to finish.

“If we take on a job and are to be judged on our work, it is to be based on the whole job, rather than just pressing using plates that have been made elsewhere,” he says. “It gives us more control, flexibility and facility to fix issues internally should there be any, which do arise from time to time with cutting and plating."

“I guess our structure has a lot more to do with setting up when there were no local cutting or plating facilities – as there were prior to the closure of the local vinyl industry in the early ’90s – when access to US or European facilities was a lot more limited and our freight more expensive.”

It’s a model Zenith remains committed to, having recently undergone an infrastructure upgrade three years in the making and revolving around an additional steam boiler to increase capacity. (“The heating process in pressing vinyl records is primarily via steam and steam pressure and is a non-negotiable necessity to carry out vinyl record pressing,” he explains.) The business is soon to commission a 1978 Lened Automatic press alongside its four manual Vintage Alpha Toolex pressers (and 1974 Neumann VMS 70 cutting lathe), too.

Zenith’s ties to the international industry actually concern its engineering CNC machine shop. Since 2018, Zenith has developed its own moulds and dyes (which Rigby says do the heavy work in the pressing process) and is currently road-testing them in plants in Europe, the US and South America, hoping to improve their efficiency through the adoption of its tooling.

And the million-dollar question...

I couldn’t bypass the opportunity to ask pressers their thoughts on how coloured vinyl affects sound quality, since to some the choice between black and colour seems akin to that between a lobster roll or lobster-flavoured ice cream. It looks damn good (I mean, have you seen Tycho’s 'Drive' on orange and red marble? Sexy or what?), but if quality-obsessive Jack White says black is best (flick to 38:39 in his interview with Zane Lowe) – and he isn’t alone – it is a hard rebuttal to ignore.

“It’s a bit of a mixed bag,” admits Lynch, “the colours we offer will generally have the exact same sonic properties as black compound. There may be subtle differences in surface noise characteristics due to variations in plastics. Overall, the impact on sound quality is minimal, if present, and most listeners won't notice any significant difference between coloured and black vinyl records.”

Program Records doesn’t currently make splatter or picture designs, so Lynch couldn’t speak of them from a manufacturing perspective, though Zenith Records does offer a disclaimer for the former which reads: ‘Our aim is to ensure we achieve good sounding records, however the splatter process can introduce additional noise and must be taken into account when you order.’

“Black is always a safe bet!” says Lynch.

Perhaps that just sways me towards choosing Slowdive’s Everything Is Alive on black vinyl over Ludovico Einaudi’s Live At The Royal Albert Hall on red for my Record Store Day purchase, then. Or perhaps I should divert my weekend spend to the debut album by pop-folk Queenslander duo The Dreggs instead. After all, Lynch offers a poignant concluding message: “I think ahead of Record Store Day it's important for anyone who loves their local shop or their local scene to head out and buy a local band’s record – not just a special RSD one!” Right you are.

MORE:

Read all of What Hi-Fi?'s Vinyl Week features

Our pick of the best Record Store Day 2024 releases – Gorillaz, Pearl Jam, Sonic Youth and more

How to store records: 9 tips for keeping your vinyl tip-top