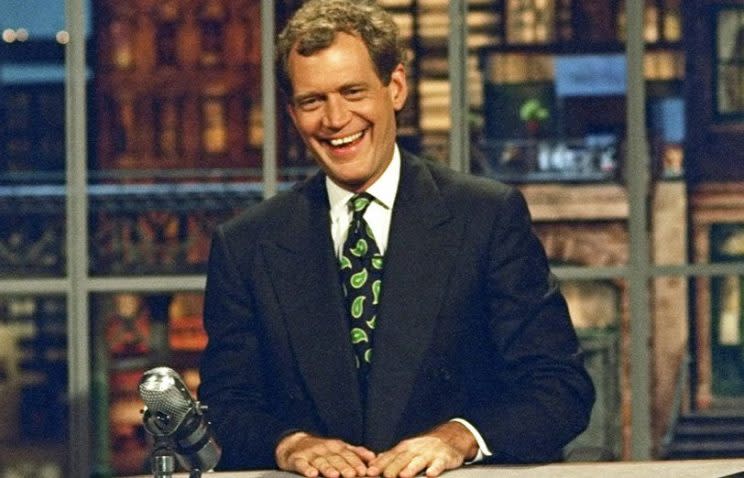

New Letterman Biography Proves His Greatness and His Weirdness

Jason Zinoman’s Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night (Harper), on sale Tuesday, is a forensic biography of — I’ll just put this out here now, so you know where I stand — the greatest talk-show host ever. Zinoman, who covers the comedy beat for the New York Times, comes at David Letterman as a fan, as a critic, and as a reporter. The author knows he has to include Letterman’s failings, both professional and personal, yet his goal is to make his subtitle ring true: Letterman as “the last giant” of a TV genre that is now overrun by lesser mortals seeking niche audiences and demographic shards.

For Letterman, hosting a talk show was the TV equivalent of writing the Great American Novel (yes, another now-outmoded ambition). To host a popular network talk show when Letterman started doing it in the 1980s was to insinuate your personality into multimillions of minds five nights a week — to have your personal sense of humor characterize a good chunk of the culture.

Zinoman lays out Letterman’s ambitions well, telling the story of a young goofball’s checkered career (disc jockey, weatherman, standup comic, game show guest) on through key collaborations with comedy writers (foremost among them Merrill Markoe, the woman who pushed Letterman to do his most adventurous work on his NBC Late Night show), and his titanic struggles to reach the summit (The Tonight Show), only to discover that the struggle was its own reward. Zinoman does this via diligent reporting and the kind of reportorial access only a New York Times reporter could gain — the supposedly press-shy Dave has always been a sucker for institutions of power.

Thus Zinoman has fresh things to say while traveling down well-trodden trails, such as the late-night-wars saga with Jay Leno; the 2009 sex scandal with an intern/assistant, and Letterman’s slow but steady withdrawal — first from his staff, then from his interest in his broadcast, and finally, the way his retirement became a vanishing act that allows him to magically resurrect, behind a flowing white beard, in unexpected places, such as his recent speech inducting Pearl Jam into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame at Barclays Center.

Zinoman is also full of ideas and theories about what made Dave tick, and what his audience liked and disliked about him. The Last Giant completely buys in to the notion that Letterman was, above all, the avatar of late-20th-century irony: “David Letterman made ironic detachment seem like the most sensible way to approach the world.” Reading Zinoman’s book, it occurred to me, not for the first time, that the High Priest of Irony designation was really just a lit-crit label for his comedy style. Dave had no real interest in exploring irony as a comic device — it was simply his fastest route to both self-protection and laughs. Indeed, irony ultimately proved as insidious and as potentially debilitating to Letterman as the clogged heart vessels that prompted his 2000 surgery.

I like that Zinoman’s book is so extensively opinionated, because it’s fun to disagree with him. (Did Letterman “imitate the style” of early Tonight Show host Jack Paar? No! In thunder: Dave had little use for Paar’s naked emotionalism.) But the opinion doesn’t dominate — it’s the interviews with scores of staff writers, producers, and performers who worked for Letterman that make this book captivating. I freely admit that I’m the kind of Dave-aholic who would have been happy if Zinoman had appended the transcripts of certain interviewees, such as former Letterman writer Randy Cohen, who is always an acute observer.

Zinoman allows some autobiography, placing himself in the ideal Letterman demo: He got hooked during Dave’s NBC glory days, when the author was in high school — the most impressionable time to be exposed to the host’s loopy absurdism. By contrast, those in Letterman’s employ — unlike his fan-base — were forced to become Letterman superfans, because you had to be attuned to the boss’s merest twitch or tongue-click of disapproval to gauge your workplace status. This is what Zinoman diplomatically refers to as “the creative tension between him and his staff.” “You could do a chapter on Dave’s neck,” says staff writer Steve O’Donnell at one point, and I’ll add two things about that: One, Zinoman explores the cricks in Letterman’s head attachment thoroughly for what they reveal about his behavior (“It affected a lot of things,” notes O’Donnell; “it is partly responsible for Dave’s imperious reputation”), and two, I realized I would indeed read a whole chapter on Dave’s neck if it had been included.

I knew Zinoman was on my wavelength when I saw he was willing to go into Letterman deep-cuts — how many pages he was willing to devote, for example, to Meg Parsont. Does that name not ring a bell? She was the book publicist whose office was across from the Late Night NBC studio, whom Dave spied one evening in 1991, called on the air, and struck up a comic-romantic relationship with. (Zinoman says Letterman called her from his post-monologue desk about once a month for three years.) She was both utterly charming and almost entirely faceless, warmly engaged by Dave’s charm and yet literally distant from him. Is it any wonder Parsont was both comedy gold and, on a certain chaste level, Letterman’s ideal woman? Zinoman’s willingness to seek out Parsont for a fresh interview — and to hang on her an entire theory of how Dave-and-Meg narrowly presaged the era of reality TV the author dates as beginning with MTV’s The Real World in 1992 — demonstrates the extent to which Letterman acolytes will extend their (okay, our) devotion. If you’re not gratified and transfixed by Zinoman’s explorations of the Meg phenomenon, or in his effort to ascertain precisely which staff writer ought to be credited with the invention of the Letterman Top 10 List, you may find yourself skimming The Last Giant, looking for the funny parts or the dirt.

As I’ve written more than once — and it’s a position Zinoman echoes — Letterman was the summation of all of the Tonight Show hosts who’d preceded him. He had the brainy zaniness of Steve Allen, the artfully decorated confessionalism of Jack Paar, the icy command of Johnny Carson. And then Letterman went beyond and above them, applying those layers of irony like shellac, a coating that would eventually render much of his latter-day comedy brittle and cracked with self-loathing. As tired as many viewers became of Letterman, one thing was certain: You could not be more sick of David Letterman than he was of himself.

Increasingly, Letterman is a figure of an era fading into the mist of nostalgia. All the more important, therefore, to have Zinoman’s reportage while the host and his collaborators are still around. Right now, Stephen Colbert is engaged in a sort of inverse-Letterman move, taking the Late Show back from Jimmy Fallon’s Tonight Show lead in the ratings race. When I interviewed Letterman in 1995, he was saying, “We’re still very competitive. We want to win. I have a feeling things will correct themselves in the not-too-distant future.” It only took replacing him and 22 years for that to occur. But Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night will remind you why all that once seemed so important.

Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night (Harper) is on sale now.

Read more from Yahoo TV:

? ‘Dancing With the Stars’ Recap: My Most Memorable Year

? ‘Better Call Saul’ Postmortem: EPs on Saul’s Arrival and a Possible Gene Spinoff

? The Abused United Airlines Passenger is Now a TV Star