‘Manhunt: Unabomber’ Preview: Sam Worthington on Giving FBI Profiler Jim Fitzgerald His Due

On Aug. 1, Discovery premieres its gripping eight-episode anthology series Manhunt: Unabomber, starring Avatar‘s Sam Worthington as Jim “Fitz” Fitzgerald, the FBI agent and criminal profiler whose pioneering use of forensic linguistics helped identify and capture Ted Kaczynski (A Beautiful Mind‘s Paul Bettany), the domestic terrorist who killed three people and injured 23 with mail bombs over a 17-year period, in 1996.

The fact that many people don’t know Fitz’s name — he’s not even mentioned on Kaczynski’s Wikipedia page at the moment — is why Worthington signed on. “When I started reading the script and doing some research, you discover that 99 percent of this story has never been told. That was what made it exciting,” he says. “When you dig into the story, the main thing was like, ‘Why have we not heard about him?'”

What also hooked Worthington (and Bettany) was that the story, as told by writer Andrew Sodroski and director/showrunner Greg Yaitanes (Quarry, Banshee), draws a parallel between the two men, who both struggle to be heard and accepted for their ideas. For Kaczynski, it’s the anti-technology worldview expressed in his 56-page manifesto, and for Fitzgerald, the newest member of the Unabom Task Force (UTF), it’s the insistence that he can build an accurate profile from someone’s writing: What kind of person would format a document like that? What do the words and phrases used — or not used — tell you about where and when he grew up?

“I always thought that the Ted Kaczynski character is using physical bombs, and then Fitz’s character has emotional bombs, in the sense of he is destroying his world around him in order just to keep passionately pursuing his firm way of thinking and his own ideals,” Worthington says. “It’s not necessarily the capture of the Unabomber that I think interested Fitz; I think it was also the fact that he created a whole new system and a whole new way of looking at crime, and that acceptance is what kept him pushing himself. The guy was just a beat cop — that’s all he was in the past. He was always trying to push himself, and even today, I think that kind of attitude, always wanting to be heard, would make people turn around to you and say, ‘Hey, look, can you just get out of my face a bit?’ That kind of plays into the fact of why he went unknown for years. If you’re longing for that recognition, sometimes you got to calm down rather than just pushing it into people’s faces.”

Yahoo TV: Jim Fitzgerald is a consulting producer on the series. What kind of insight did you get from him?

Sam Worthington: I held off on talking to Jim for a long time, because if I ask you how you were 20 years ago, you’re going to give me your filtered version of yourself — you’re not going to give me the absolute truth. So I read books, couldn’t find anything about him, and it was like, “I don’t understand.” I still didn’t know why he got hidden. And then I came across all this stuff that around that time everybody was taking credit for the Unabomber. Even the guys that pointed them in the direction of the shack were saying, “I caught the Unabomber.” Someone said there were bumper stickers out at the time saying, “I caught the Unabomber, too,” you know? I think because he was such a prolific terrorist, who had gone uncaptured for years, everyone felt a sense of relief and wanted to be involved and part of it. That is what I got from all my research.

Eventually I managed to locate some transcripts that Jim had done for interviews, and it started to then all come through. I looked at a lot of transcripts of him talking to the writers and the director. I watched a lot of YouTube videos of him, because he’s had quite a prolific career after the FBI, in books and consulting. I gave him a questionnaire, because I wanted the negatives as well as the positives, because that’s what interested me. I thought if I’m sitting in a room with the guy, he’s a profiler, so he’s going to be playing games with me, and then I’m profiling a profiler, so we’re never going to get anywhere and it’s never going to be truthful. Giving him the questionnaire gave me a bit of distance and then he’s just looking at the words and literally giving me something from himself without actually trying to trip me up or figure me out.

He didn’t shy away from the personal stuff. He didn’t shy away from anything, and I really respect that, because it gave me a way in. When you accumulate all that material, you can find a pattern of what the essence of this man is and what his drive may be. Once I met him, we were already filming, and I could kind of see if my way of going into the part matched him, and it certainly did. I had the drive right on, but that drive may be a negative thing that Fitz can’t see. You have to kind of try to find another way in without sometimes going to the actual source, because they can actually lead you down a false path.

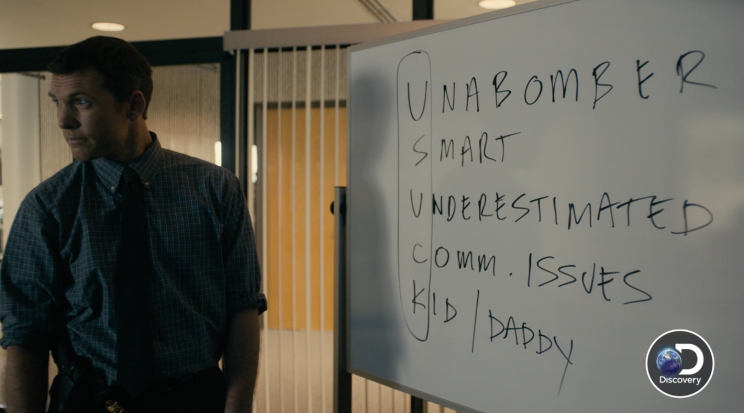

One of the best moments in the two-hour premiere (as seen in the video above) is when Fitz is fighting his bosses for access to the Unabomber’s 35,000-word manifesto, which they don’t feel an urgency to give him until after forensics has finished with it. To show them what he was able to glean from a one-page letter, Fitz writes words on the whiteboard — the first letters of which spell out USUCK. Did that really happen?

No, I made it up. Originally, the scene was just a speech where you go, “Oh, he’s a good profiler.” Then I woke up one day and I went, “I wonder if I could find words that match the speech?” The “USUCK” was something that I thought, “Well, that matches, because he can do puzzles.” I remember my wife woke up at about 7 a.m. before I went to work. I said, “Check this out.” She thought I’d lost my mind. She goes, “Tell me what’s going on here. This is very weird. You shouldn’t be dreaming about this.” Then I took it in, and I was so nervous to show people, but I said, “It’ll make the scene better. It doesn’t just have to be about the profiling speech — it shows you the mechanics of how his brain operates. I think I’ve got something that’s pretty darn cool.” I showed Greg and the writer and they went, “Oh, we’ll take credit for that. Thank you very much.” [Laughs] But yeah, that was just something that I came up with because I thought it was funny. I had other words too, but we had to watch our rating. [Laughs]

It was a case of here’s a show that is about language, and it’s about dialogue and dialect and idiolect and axioms and variant spellings — that on the surface sounds like a very boring show. I kept saying to Greg, “How do we make each scene kind of jump a bit, or bring a bit more?” All the stuff like [Fitz tossing a football while thinking], that was stuff that we came up with on the fly. I said, “It should just feel exciting. These guys get excited by reading. They get excited by language, and if we’re excited by it, then an audience will be excited by it.” So the more we found it fun and playful and amazing, the more hopefully an audience does too.

There’s also an interesting physicality to the way you play Fitz. When he’s getting belittled by his bosses, we can see him wince or shrink for a second.

If someone’s trying so hard all the time and not rocking the boat, by trying that hard they’re always rocking the boat. [Laughs] It’s almost like when kids go to school for the first time: They don’t know how to fit in and they’re scared to speak up, and when they get attacked they go into their little crab shell. I wanted a lot of that energy. I wanted it to feel like a bomb that could explode any time, just through his own passion and desperation to be heard. So he’s always got movement. He’s always just about to speak and someone interrupts him. It’s a totally different energy than my own, so I was kind of wound tight for the whole of filming. In the arguments you’re having with the director, I kept saying to him, “We’ll be best mates after this, because I’m not like this energy. I’m not this Molotov. I’m not this wound up.” [Laughs] But I looked at it as though he’s his own worst enemy. He’s his own bulldozing bomb. And the same thing when he’s attacked, finding something to pick at and shy away, and that kind of insecurity in a crowd, that kind of insecurity with yourself when you’re actually on the right track.

It was important to Paul Bettany that Manhunt tell Ted’s backstory, too — which is the heart of Episode 6 — so that the conversation can extend beyond “this man is a monster” and into his beliefs and the events that bred them. Great storytelling always does that, but it still feels brave to show any empathy toward a bomber who caused this much damage.

Because you don’t want to glorify the Unabomber. In Episode 8, you hear the actors act out the transcripts of what the victims said at the court cases, and that’s when it really struck me: This did happen. This guy is a murderer and deserves to be locked away, because the suffering continues — the families that got affected 20 years ago are still being affected now. You have to always handle that with some level of delicacy, but for good storytelling, showing the empathy with how this young kid got twisted and turned to become this sociopath and psychopath, that’s intriguing. And in turn, you can then play on the dark side of Fitz. You can push him and show how destructive his passion could be by losing and dismantling his own family and kind of not having a care for anything else, becoming myopic in the pursuit of his passion to catch this guy.

How do you think the issues raised in the series are relevant today? Seeing the kind of hate that can build in someone when they feel so ostracized, for instance, feels timely.

I’ve read the manifesto many, many times now, and I actually do believe in what Ted Kaczynski was saying and emphasizing. I do not believe in how he wanted to get his words out there. I think that is just terrorism full-stop. But if you go back to what he’s saying about us becoming slaves to these systems and technologies that we created to help us, that is happening. Whether we like it or not, when the phone rings, people do jump. One other thing Greg promised me from the beginning was that we’re going to pose a lot of questions about technology and society, the secrets that people have on their computers and the reliance that we have on this technology, and the fact that we are kind of moving away from each other and the environment and secluding ourselves at the same time as thinking that we’re having more connectivity. I believe we are doing that, and I think that if you took away how the man tried to get his voice out there, he was onto something. I think that’s hopefully what makes this a bit more relevant as well.

The two-hour premiere of Manhunt: Unabomber airs Aug. 1 at 9 p.m. on Discovery. Watch the first hour now, below.

Read more from Yahoo TV:

? ‘Game of Thrones’ Recap: Another Queen Bites the Dust

? ‘Big Brother’: Could Kevin Actually Win?

? ‘The Walking Dead’: 20 Things You Didn’t Know About Jeffrey Dean Morgan