From Supporting Roles to Star Status, Titus Welliver Takes the Lead on ‘Bosch’

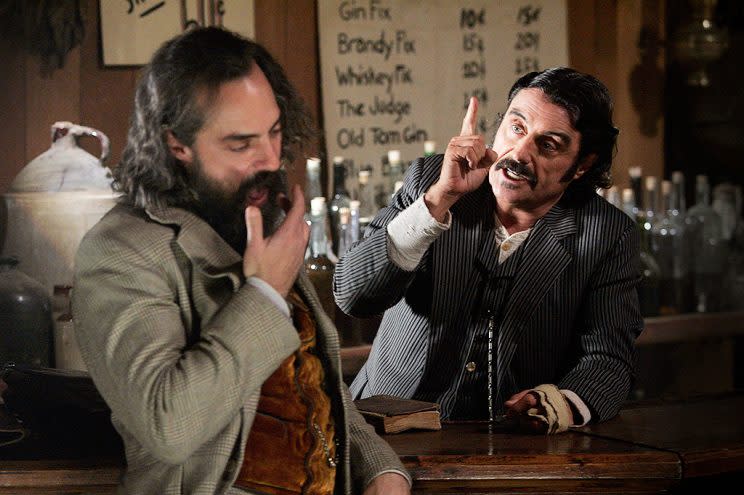

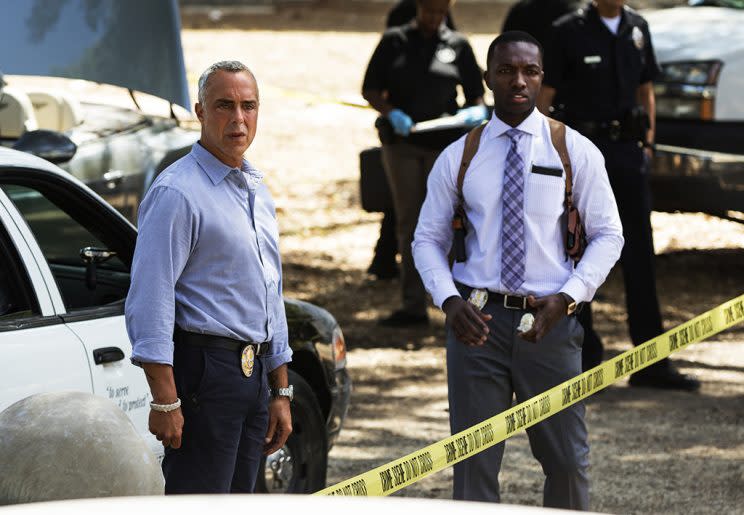

Everybody’s gotta start somewhere, and for Titus Welliver, as it was for many a character actor before and after him, that somewhere was a part that didn’t even merit a name. Before the salt-and-pepper actor with a superior smirk became a constant fixture on TV screens in acclaimed series like NYPD Blue, Lost, Deadwood, The Good Wife, and Sons of Anarchy, he jump-started his career as the “redneck in a bar” in the 1990 Charlie Sheen vehicle Navy Seals. And now after years of supporting roles, one-off appearances, and recurring parts playing bagmen, kingpins, doctors, prosecutors, and even a reverend and an avian monster on Grimm, he has finally gotten his well-deserved shot at being the name and the face in the ads and billboards with Bosch, the L.A. cop show based on Michael Connelly’s bestselling book series, which begins streaming its third season on Amazon today.

Welliver spoke with Yahoo TV about how he felt being labeled a character actor, the transition to TV leading man (“The only thing that’s different really is the hours,” he jokes), why the character Bosch fascinates him, and more.

Yahoo TV: Do you mind being referred to as a character actor? Is there a stigma associated with being labeled that or is it a good title?

Titus Welliver: First of all, thank you for the support. I think character actor is kind of a way of being stigmatized to a certain degree. I always say, “Every actor’s a character actor.” But it became the thing to describe the sort of people who alter their physical presence with makeup or massive weight gain or loss or who kind of disappear into characters. Guys like Dustin Hoffman, Brando, Alec Guinness, and De Niro are character actors. And who wouldn’t want to be filed into their company? But I think sometimes it connects to someone who is not necessarily the central character of something but is more of a supporting role. It presents an opportunity to kind of disappear [into different roles], and in that way, it fits. I have been really, really lucky that the characters that I’ve been given the opportunity to play are very different, and the fun of being an actor is to attempt to disappear to a certain degree. I don’t wear any kind of disguises or masks as Harry Bosch. If somebody sees me on the street, they know who I am if they’ve watched. But I think it’s sort of an evolution of being a child on Halloween and finding the right costume to sort of disguise oneself.

Sometimes it seems to imply someone who can’t be the lead because they are not handsome in a classic way or not muscular enough to be the hero doing all the action sequences. But usually, I find they grab the beefier parts with the better dialogue. Like on procedurals, the most interesting bit is finding out about the bad guy.

I agree. I think you have the central characters [that you watch every week], but the [producers] up the ante with the recurring characters and the guest stars — these sort of flashy roles that the central characters can bounce off of. In Bosch, that’s not necessarily the case because all the characters that occupy that universe are balanced. The villains certainly are really interesting and well-realized too, but it is balanced. The character of Harry Bosch is a really multifaceted, flawed character that is like a character actor role.

Is that what drew you to want the job?

It’s meaty. And while Harry evolves circumstantially, there’s a sameness and steadiness about him that makes him interesting. Part of that is his humanity, because he is a very haunted guy, but he’s also a man of action. He’s not someone who’s overly emotionally demonstrative. He’s not a flashy guy. He’s a guy who wants to blend in and go unseen because he’s an observer. That’s what I find very appealing about him. And often when one’s placed in the position of being an observer, the idea is to kind of blend in rather than to stand out. And certainly, his line of work is very much that. He wants to hang back. This is the guy who, by his own admission, deals with darkness and inhabits the darkness. And when you inhabit the darkness too much, it can penetrate you.

We have definitely noticed an increase in people we’d once have considered to be character actors grabbing lead roles in TV shows, and a growth in TV shows that revolve around big ensembles populated by character actors — Deadwood, Justified, Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul, Game of Thrones, and The Wire, the latter of which spawned several folks now on your show. Do you think that is a fair claim, and if so, why do you think that is happening?

I think David Milch and Steven Bochco are the champions of creating the perfect ensemble show, shows where we knew who every character was and knew their stories. That speaks to masterful storytelling on Milch and Bochco’s part. I think to a certain degree, there is an attempt to gravitate toward realism so leads don’t need to look like Tab Hunter or Rock Hudson. I don’t consider myself that. I mean, I’m not a Shar-Pei, but I don’t look like Brad Pitt either. So they’re kind of redefining what dictates a leading man or a leading woman. You don’t have to have that kind of stereotypical starlet or chiseled or WASP?y features in order to be considered a hero. And that’s good news for guys that look like me [Laughs]. But what’s funny is, if you look back at the old Quinn Martin shows of the ’70s, William Conrad as Cannon, or Buddy Epson as Barnaby Jones, certainly Colombo, Beretta — these guys were all kind of off the beaten track, but they were the leads of the shows. You’d follow them into a burning building because there was a level of gravitas to those characters. And Cannon, if he had chased a suspect half a block, he would have had a massive coronary, which is probably why William Conrad shot a lot of people on that show.

It doesn’t get much better than a delicious antihero. No offense to Timothy Olyphant, who was supposed to be the hero of Deadwood, but I would think Ian McShane’s Al Swearengen is the first thing that comes to people’s minds when that show is mentioned. Even though he was deplorable and less classically handsome.

That’s why I always liked Dennis Franz as Sipowicz [on NYPD Blue]. I mean, this guy was a drunk, a bastard, a bit of a racist, a rule bender, and yet, he was the character that everyone grew to love because he was a profoundly damaged and flawed guy. That’s what made him charming and accessible. He was not a likable guy, and yet you knew that there was a part of him that was in the service of right. And people gravitated to him.

Did you change your process to play a lead character, or was the approach the same as you would employ for a five-episode arc or a small guest appearance?

My approach and my process as an actor are consistent with how I operate as far as doing research and creating the character. The biggest difference, for me, is the amount of hours that I work and the amount of screen time that I have. And obviously, there’s a level of responsibility when you’re the lead on a show. From a place of integrity, there’s a bigger investment. But artistically, and certainly intellectually, and from a work ethic [standpoint], I’m a big believer in the cliché that there are no small parts, only small actors. If you have integrity, you have to approach everything you do as an actor with the same amount of respect and commitment. Show up and do your job and do it well, whether you’ve got five lines of dialogue or 75 lines of dialogue. That’s what you do. You’ve got to come in and facilitate the telling of the story. So in that way, no, it’s not really different.

Why is Harry Bosch a great part to leap into the leading man world with? And is it at all constricting to play a beloved character where so much about him is established in the novels?

I certainly felt an immediate connection and kinship to the character, and then, a very, very strong sense of protection of the character. And it’s not that I really had to protect him, because I’ve got Michael Connelly there and Michael wants the same thing. We’re very much on the same page. I had a short period of preparation for Bosch. So I had to dive headlong into it. But I knew what I wanted to do immediately. Because the character was so clearly realized on the page in the books, I wasn’t making stuff up. I’ve brought certain things to the character that were not in the books, and I run those up the flagpole. I have ideas occasionally. But I think the character that you see on the show, his attention and his center, is 100 percent true to the character in the books. There are times where there will be stuff on the page, and I’ll say, “I don’t think he should say anything.” And that’s what I love about Harry — when he speaks, it needs to resonate. He’s not monosyllabic, but he doesn’t say anything unless he’s got something to say. People sometimes perceive him as being a prick, but I don’t think that he is. He doesn’t subscribe to the kind of societal norms of politeness. He’s not a guy who comes into a room and says, “I hope I gain acceptance here. Let me be gregarious and charming.” He comes in and says, “Well, this is who I am, warts and all.” That’s refreshing.

Especially in this industry town.

I subscribe a bit to that. As an actor, we all want to win the day and be liked. At the end of the day though, it’s about your work. You can come into a room and be charming and lovely, but that’s not going to get you the job. The substance of your work and what you can do is. Sometimes that is the misconception of Harry. More than once, there has been a guest actor on the show, and they’ll say to Jamie Hector or one of the [other] actors, “Titus doesn’t seem to like me. He’s very distant. But in between takes, he’s very gregarious and interacting with everyone. But when we’re in the middle of a scene, he’s not really necessarily looking at me.” Jamie told me that and then he started to laugh. He said to the actor, “No, that’s not Titus. That’s Harry.” If he doesn’t have use for someone, there’s a bit of a parallel stare. He won’t necessarily engage. And I think that’s part of who Harry is. There’s a thing that my father used to refer to, a kind of engagement, where sometimes you just have to look at somebody’s forehead and present some sense of engagement when you’re not engaged. Although Harry can be rude and extremely dismissive. He doesn’t suffer fools. That comes out of his frustration for people who are inept and don’t place the same level of commitment and discipline and importance to police work.

Can you pick a favorite character, or the most exciting TV show you have been a part of?

I’ve been really, really fortunate that with very, very few exceptions, most of the characters that I’ve played have been really stimulating or at least taught me something about acting and improved my process of creating a character and playing with other actors. And certainly, I find every few years a character comes along that challenges me and allows me to progress to another level. It’s always my hope — and for me, it’s not always the case — that I become the better actor and learn something [from each new part]. That’s the great reward. That’s also daunting when you sign up to do a series. Will this character sustain me? And for someone who has ADD, that’s a big trick. I sensed immediately when I was reading the pilot script of Bosch that this was a character that would challenge and sustain me for many years to come.

Is there a character that you wish you could have a do-over on? Something you wish would come to you now, knowing what you know now, instead of earlier in your career?

Not really. And I don’t mean to sound arrogant. I put my best foot forward. One of the things that I realized as an actor is, I work better in an immediate sense, organically. I don’t like to be over-rehearsed. Obviously, when you’re doing theater, it’s a very, very different muscle that you operate with, but there’s something kind of liberating about making a choice and sticking with that choice and seeing where it takes you. As a result of that acceptance and honoring that within myself, I edit within camera when I’m working so that I don’t put something out there in the universe that I don’t want people to see. I don’t want to get caught acting. As a painter, I understand it. Both of my parents are artists, and something I noticed was that my father and mother never had their work hanging in our house. I asked my father [about it] and he said, “I don’t want to look at it. When the painting’s done, the painting’s done. If I have it in front of me, I’m going to rework it and rework it.” I take that same position as an actor. I do the work, and then, to a certain degree, divorce myself. I am quick to change the channel if I am sitting at home and an episode or a film comes on.

Man, that means you are depriving yourself of some good TV.

I usually watch stuff once, or I watch the parts I am not in. But if I am sitting with one of my children or my wife and they want to watch, I usually dismiss myself quickly. As a painter, I never hung my work in my house. My late wife used to go into my studio and take pieces and hang them, and at first, it made me insane. I expressed my issue with that and she said, “It isn’t about you. I like looking at your paintings. If you don’t want to, don’t look at them.”

But one of the great gifts of Bosch is that I can separate myself and I can actually watch and be engaged in it. I usually watch the episodes as they are edited into a more final state, and for some reason, I can divorce myself a little more than usual and enjoy the other actors’ work. I’m not insane. I do recognize that I am Harry, but for whatever reason, I can separate myself enough to watch when my family wants to without squirming or rethinking everything.

Seasons 1-3 of Bosch are streaming now on Amazon Prime.

Read more from Yahoo TV’s Salute to Character Actors:

Introducing Our TV Character Actor Hall of Fame

TV’s Top 20 Character Actors Working Today

How Hall of Fame Character Actor Stephen Tobolowsky Approaches Each Role

How Margo Martindale Became ‘Esteemed Character Actress Margo Martindale’

How Dylan Baker and Becky Ann Baker Became Mr. and Mrs. Character Actor

‘This Is Us’ Dad Ron Cephas Jones Talks His TV Takeover