Last ride for the General Lee? 'Dukes of Hazzard' streaming future uncertain as Confederate symbols face renewed scrutiny.

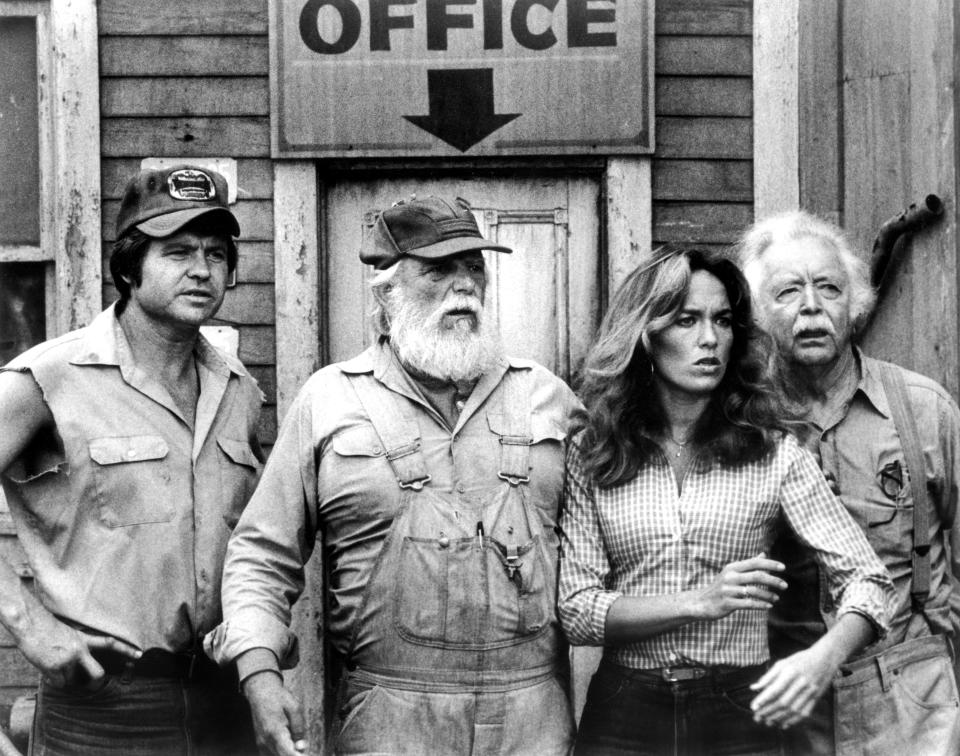

It looks like those good ol’ Duke boys are going to be in need of a new home. Since 2018, all seven seasons of CBS’s quintessentially ’80s series The Dukes of Hazzard have been available to stream on Amazon, first as part of the Prime Video library and currently via IMDb TV, the streaming arm of the much visited website. But a recent report from Vulture suggests that moonshine-running brothers Bo and Luke (played by John Schneider and Tom Wopat) and their cousin Daisy (Catherine Bach) might be facing an eviction notice.

The series is the latest pop culture artifact to face renewed scrutiny in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests inspired by the death of George Floyd, which in turn have inspired Americans to confront the legacy of racial injustice and exclusion in popular entertainment as well as policing. The past few weeks have already seen the cancellation of TV shows like Cops and Live PD and the temporary removal of Gone With the Wind from HBO Max, as well as the discontinuation of famous brands like Aunt Jemima. If The Dukes of Hazzard joins them in exile, it’s because the show wears its offending symbol on its sleeve — or, more accurately, on the roof of Bo and Luke’s signature car: a bright orange 1969 Dodge Charger with a Civil War namesake — Gen. Robert E. Lee — and a Confederate flag emblazoned up top.

That flag has landed the General Lee in hot water before. Five years ago, the show was benched by its previous home, TV Land, in the wake of the Charleston church shooting by white supremacist Dylann Roof. At that point, Warner Bros. — which produced the original series, as well as its various spinoffs and follow-ups, including the 2005 big-screen version — ceased licensing the Dukes’ ride for toys and other merchandise. So the news that The Dukes of Hazzard might lose another venue due to its prominent placement of the Confederate flag strikes series co-star Ben Jones as a familiar tune. “That’s no surprise,” Jones tells Yahoo Entertainment from his home in Virginia. “And it’s almost meaningless. No one knew it was on Amazon Prime unless they ran across it when they were searching around there. I think it would be a shame, but they all have caved over different points in time.”

Jones’s history with the Dukes predates the show; one of his earliest acting gigs for the North Carolina native came in the 1975 film Moonrunners, which was retooled four years later into The Dukes of Hazzard. He was the first actor to audition for the series, and spent seven years playing Hazzard County’s resident mechanic, Cooter Davenport, who helped Bo and Luke in their weekly attempts to foil the plans of property baron Boss Hogg (Sorrell Brooke) and stay one step ahead of bumbling lawman Sheriff Rosco P. Coltrane (James Best). While Jones pursued other careers after Dukes went off the air in 1985 — including a stint in Congress as a Democratic representative from Georgia — he describes himself as a “steward” of its legacy, a legacy that he increasingly views as being under attack.

“I end up defending myself and my culture all the time on these issues,” says the 78-year-old owner and operator of Cooter’s Place, a Dukes of Hazzard museum and shop that has locations in Tennessee and Virginia. “The Rebel flag on top that car has been seen by hundreds of millions of viewers for 40 f****** years. You can’t just say that we’re going to be politically correct and cave to whatever they want because it’s insensitive. We had a huge Black audience, and Black people come in all the time to our stores saying, ‘I loved that show. I watched it with my family.’”

You can’t just say that we’re going to be politically correct and cave to whatever they want because it’s insensitive. Ben Jones

Growing up in the early ’80s, journalist Kevin S. Aldridge was one of the Black fans that Jones describes. “When I was a kid, that was my favorite show,” he tells us. “It was this fun, jokey police chase adventure show that didn’t really delve into super-serious topics. I remember that all I wanted for Christmas one year was a Dukes of Hazzard electric racing set where the car would jump over a ravine like it would on the show. I got it, and I played with it all day that Christmas!” At that age, the General Lee struck him as a “cool car,” like the Batmobile or KITT. “The symbolism behind it was completely lost on me,” remembers the now 45-year-old Aldridge, who is the opinion and engagement editor at the Cincinnati Enquirer. “I don’t recall ever having any deep philosophical conversations about the show with my parents where they tried to tell me about history or anything like that. I think they wanted me to enjoy what I was enjoying.”

In a 2018 Enquirer column, though, Aldridge wrote about a moment from his childhood when his enjoyment of Dukes dimmed. While reenacting scenes from the most recent episode with his white kindergarten classmates, Aldridge tried to sit in the driver’s seat of the wooden car that stood in for the General Lee. His essay describes what happened next:

Right when I was about to sit in the driver’s seat, a few of my white male classmates stopped me. “You can’t drive because you can’t be one of the Duke boys,” one of them said, as he blocked my path. “And why not?” I asked. “Because you’re black,” he said, matter of factly. ... “Don’t feel bad,” said another of my white male classmates in an attempt to soften the blow. “You can pretend to be Cooter.”

“That was the first time I felt like I was confronting a barrier to something I wanted to do,” Aldridge says now. “I wanted to be the Duke boys, but I found out that day I couldn’t be one of the Duke boys, because they were white and I wasn’t. I continued to watch the show and love the show even after that experience, but it was a bitter moment — I remember that.”

Aldridge still expresses nostalgic affection for The Dukes of Hazzard, although revisiting the show exposes the racial elements that flew over his head as a child. For example, while Jones argues that Dukes was “color-blind” in its approach to race, Aldridge says he recalls very few black actors appearing on the show at all. “It just goes to show how African-Americans in this country who have been fighting for equality and equal treatment for so long, you don’t realize how much of white culture gets normalized for you when you’re a kid.”

Meanwhile, the Confederate flag on the General Lee is now impossible for him to overlook. Aldridge credits his higher learning at Wittenberg University for bringing him face-to-face with the meaning of the flag, as opposed to what he calls the “whitewashed version of history” he was taught in grade school. “Once I started to learn more about the Civil War era and what the Confederate flag symbolized — the idea of white supremacy and the continuance of the enslavement of Black people in America — it does make you look at the show very differently.”

Not coincidentally, colleges are among the institutions that Jones targets for turning the tide of public opinion, not only against The Dukes of Hazzard but also what he pointedly refers to as his heritage as a Southerner whose ancestors fought for the Confederacy, and who joined the civil rights movement in the 1960s to fight for equal rights. “This didn’t start until the 2000s,” he argues. “For all those years the show was on the air, we never got a complaint. Then it was, ‘Oh, this is bad,’ because the NAACP said, ‘Any display of [the Confederate flag] is bad.’ And then politicians got scared, and corporations got scared, so it’s gone berserk. Who gets to decide these things? Is it just the academic left or is it the people who have the right to an opinion, and that opinion should be understood and accepted.”

“Once I started to learn more about the Civil War era and what the Confederate flag symbolized, it does make you look at the show very differently.” Kevin S. Aldridge

Jones’s own opinion is that the current debate over the Confederate flag is based, in part, on a misreading of history. “It’s not the flag of the Confederate government,” he says of the particular flag that adorns the General Lee. “This was a battle flag, and it’s a St. Andrew’s Cross — St. Andrew was Christ’s first disciple, and he was crucified in that spread-eagle position. That’s what it symbolizes, and it’s an international understanding. There are 80 million descendants of the Confederacy in the United States right now. Obviously those ancestors were on the wrong side of history ... but they were of their time, and their descendants have fought in every war this nation has had since then.

“I got into politics through the civil rights movement, and I fought the Ku Klux Klan,” Jones continues. “I got my teeth knocked out, got shot at and went to jail, but we together, Black and white in the South, changed America for the better. Suddenly, we’re persona non grata because we have that symbol there. That’s astonishingly narrow, given the demographics and our history. This is a new thing, but this country ain’t a new thing, and that flag is not a new thing. So that’s the problem. I don’t have the problem; it’s a Christian cross that was used as a battle flag and people in the South still like to wave it and go, ‘Yee-haw.’ But to equate it with hatred and bigotry and evil — that’s bulls***.”

But Howard Graves, senior research analyst for the Southern Poverty Law Center, would consider that assessment of history to be equally narrow. While he echoes Jones’s description of the specific flag on the General Lee as a battle flag as opposed to an official Confederate government flag, he offers a very different account of its post-Civil War afterlife. “It reemerged in the early 20th century in the midst of an effort to recontextualize the Confederacy and bury the truth that the South seceded in order to maintain the institution of chattel slavery,” Graves explains. “And throughout history, it periodically reemerged as white Southerners by and large have tried to maintain institutions that keep Black and brown people from having equal political footing. That’s the truth of what that flag represents.”

Graves’s work with the SPLC includes monitoring the use of Confederate imagery among modern-day white supremacist groups, and he’s observed the way the battle flag is deeply embedded in their cause. “Neo-Confederate hate groups like the League of the South have stated that they’re willing to go and commit violence in defense of Confederate monuments and iconography. All of this is accompanied by images of the battle flag. At the Unite the Right rally [in Charlottesville, Va.], one of the flags we saw the most on the ground that day was the Confederate battle flag. That was a white nationalist rally that drew out hundreds of thousands of people to make sure that a statue of Robert E. Lee was not removed, and Heather Heyer died because of that willingness.”

As a Southerner himself, Graves says he understands why some, like Jones, prefer to think of the flag as a benign symbol of Southern heritage. “I believe they’re doing it honestly; they have not truly engaged with the full historical context of that flag and believe the kind of ‘heritage not hate’ myth. But I think we’re called upon to dig a little bit deeper and look at the roots and specific context of that flag. The notion that it is anything other than a glorification of white supremacy just doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.”

For now, at least, the Duke brothers’ future is up in the air; the series can still be streamed for free on Amazon Prime’s IMDb TV channel. And even if the company decides to remove it, full seasons remain available for purchase on digital services like Vudu, as well as on DVD. But the discussion around the series will continue and some of Jones’s co-stars seem open to addressing how Dukes fits into a pop culture landscape that’s no longer comfortable with the casual representation of Confederate iconography. Bo Duke himself, John Schneider, recently posted a video on his official YouTube page where he requested feedback about the show’s legacy.

“I want to know from you ... is The Dukes of Hazzard worthy of being taken off the air because of the General Lee?” Schneider asks in the video. “Was The Dukes of Hazzard a racially charged show? Was the intention of the design, the paint scheme on the General Lee a white supremacist statement in any way? If you think it was, I want to know. I really want to know. ... I know what I think, and I want to know what you think.” (For the record, that’s a far more conciliatory tone than Schneider took in 2015 when TV Land dropped the series.)

One potential way forward would be for Amazon to follow HBO Max’s lead with Gone With the Wind. After removing the film from the streaming service, it will be restored with a newly recorded introduction from Black film scholar Jacqueline Stewart that places the film in historical context. But Jones — who still displays and sells merchandise featuring the General Lee and the Confederate battle flag at Cooter’s Place — says he’s skeptical of The Dukes of Hazzard receiving similar treatment. “Who is going to write the disclaimer? What does the disclaimer say? Would it say that in the 1980s and 1990s, millions of Black folks watched this show along with millions of white folks and red folks and brown folks and yellow folks, but they didn’t know they were doing something akin to sin by watching this show? I don’t care what they write. They’re idiots. They’re scared of political pressure. They can’t stand up and do their homework. We’re here and we’re not ashamed of our history. We accept it, we understand it and hopefully the whole country has learned from it.”

The notion that [the Confederate flag] is anything other than a glorification of white supremacy just doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.” Howard Graves

Aldrdige, on the other hand, sees the benefits of attaching an introduction to the series as a way to place it in context. “There’s a real opportunity with movies like Gone With the Wind and TV shows like The Dukes of Hazzard not to get rid of them but to have a thoughtful discussion around them,” he says. “I also understand that a network or organization like Amazon has the right to determine what they want to show and what they don’t want to show. I don’t necessarily know that I’d say, ‘Shut it down.’ If you’re going to keep it, put a disclaimer or some other framing around it and let it ride.”

Aldridge is also keenly aware that Dukes’ future will ultimately be determined by the next generation of viewers — not Jones or the children of the 1970s and 1980s — and that generation will vote with their eyeballs. “When I wrote my piece, a younger millennial wrote me, saying, ‘What is this? Nobody even knows what this show is these days,’” he remembers, laughing. “In the minds of most modern millennials, The Dukes of Hazzard doesn’t even register. So I don’t think I’d be too worried about the show polluting the minds of young people today — there are many other things they’re watching that they’re more interested in.”

The Dukes of Hazzard is currently streaming on Amazon with an IMDb TV subscription.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Yahoo Home

Yahoo Home